The importance of knowing your data“Data, data, data! I cannot make bricks without clay!” Good old Sherlock, a quote for every occasion… ("The Adventure of the Copper Beeches" Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 1892) We in the 21st Century have access to a huge volume of data. More than any generation before us. And with each day that volume of data grows ever larger. One of the many consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the continuous news coverage stressing the importance of data. We are regaled daily with graphs and statistics that I imagine few people understand or want to understand. The challenge with all data is working out which are worth using and how to best use this. It is about knowing your data. In the age of AI (Artificial Intelligence) and machine learning, there is a temptation to assume that all we need to do is to ‘train’ our software, load in the data, and wait for the answer. “42” instantly comes to mind - for those of you old enough to remember the prescient imagination of Douglas Adams and “The Hitchhikers Guide to the Universe”. There is no question that both AI and machine learning have a huge potential in helping us better understand the world. Computers provide us with the capability to interrogate the vastness of our data libraries and to draw out patterns and conclusions that we would otherwise not have the time to do. The developments in these techniques are impressive. If you are not convinced check out the Google AI site (https://ai.google/). But we need to be careful. Not because AI is not useful, it is. But because there are fundamental issues around data and analytics that we must answer first:

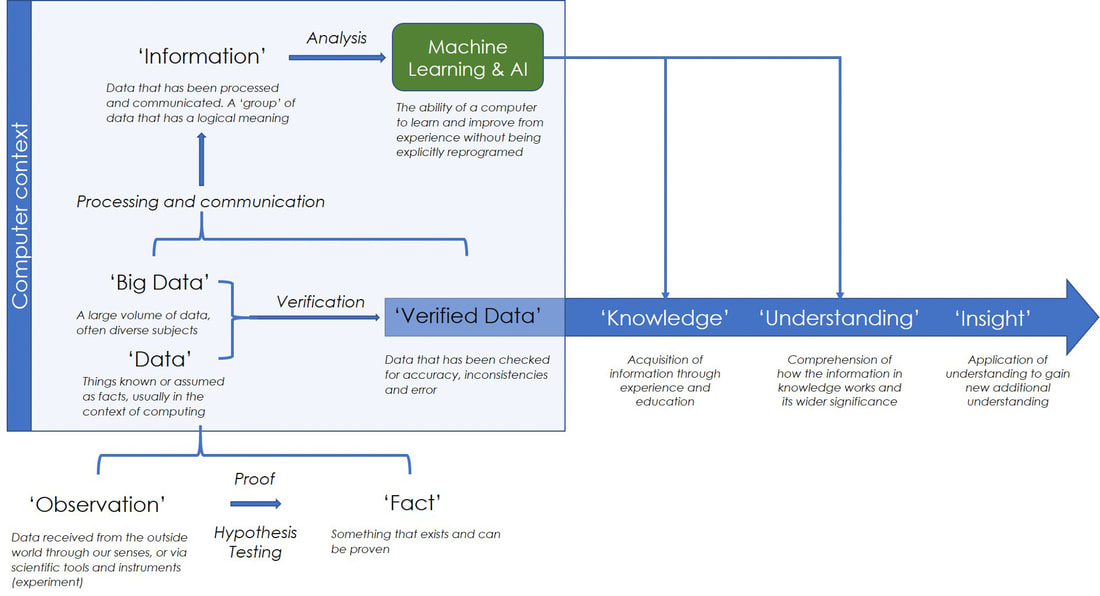

Each merits an essay in its own right. Here, I am going to focus on the third – do we trust our data? Figure 1. We in the 21st Century have access to a huge volume of data. In the last 40 years, we have seen the transition of that data from physical libraries, as illustrated here by a suite of bound scientific papers in my library, to the “1s” and “0s” of the digital age Data, data, data I have spent much of my career designing, building, populating, managing, and analyzing ‘big data’. From using paleobiological observations to investigate global extinction and biodiversity, to testing climate model experiments, to paleogeography, and petroleum and minerals exploration. Having worked at each stage from data collection to data analytics I have gained a unique insight into data, especially big data. Most databases are built to address specific problems, and no surprise, these rarely give us insights beyond the questions originally asked. But when we think of Big Data and AI we are usually thinking of large, diverse datasets with which to explore, to look for patterns and relationships we did not anticipate. My interest has always been in building these sorts of large, diverse ‘exploratory’ databases following in the footsteps of some great mentors I was privileged to have at The University of Chicago, the late Jack Sepkoski, and my Ph.D. advisor Fred Ziegler. ‘Exploratory’ databases have their own inherent challenges, not least the need to ensure that they include information that can address questions that the author has not yet thought of… That is a major problem. This requires specific design considerations, especially, as I argue you here, the fundamental importance of ensuring that we know the source and quality of the data we are using. Because it is upon these data that we base our interpretations, and from those interpretations the understanding and insights we derive. If the data are flawed then everything we do with that data is similarly flawed and we have wasted our time. This is even more important when we are analyzing 3rd party databases that we have not built ourselves. How far can we, should we trust them? In short, we can have the best AI system in the world and the most powerful computers, but if the data we feed the system is rubbish, then all we will get out is rubbish. What do we mean by data? In discussing data and databases it has become de rigueur to quote Conan Doyle: “Data, data, data! I cannot make bricks without clay!” Good old Sherlock, a quote for every occasion… ("The Adventure of the Copper Beeches" Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 1892) But what do we mean by “data”? When I started to write this article, I thought I knew. But in looking through the literature I soon realized that such terms as “data”, “Big data” and “information” were vaguely defined and used interchangeably. So, to help anyone else in the same position here is a quick look at the terminology, including some that you may or may not be familiar with. This is summarised in figure 1. A more comprehensive set of definitions is provided as supplementary data in the pdf version of this blog article. Figure 2. The relationship between data, information, knowledge, understanding, and insight. This summary figure shows the problem of current definitions (see supplementary data for further information) The fundamental progression here is from data to verified data to knowledge, understanding, and insight (see the recent Linkedin article by the branding company LittleBigFish). Admittedly, in many ways trying to define the relationships between observations, facts, data and information is semantics. For databasing we can reduce this to data and verified data, and this takes us back to the need to audit and qualify our data: the data to verified data transition. The audit trail: Recording Data Provenance and Explanation When designing and building a database we need to ensure that we include information about the data. For spatial geological data, we need to answer a range of questions about the data, including the following:

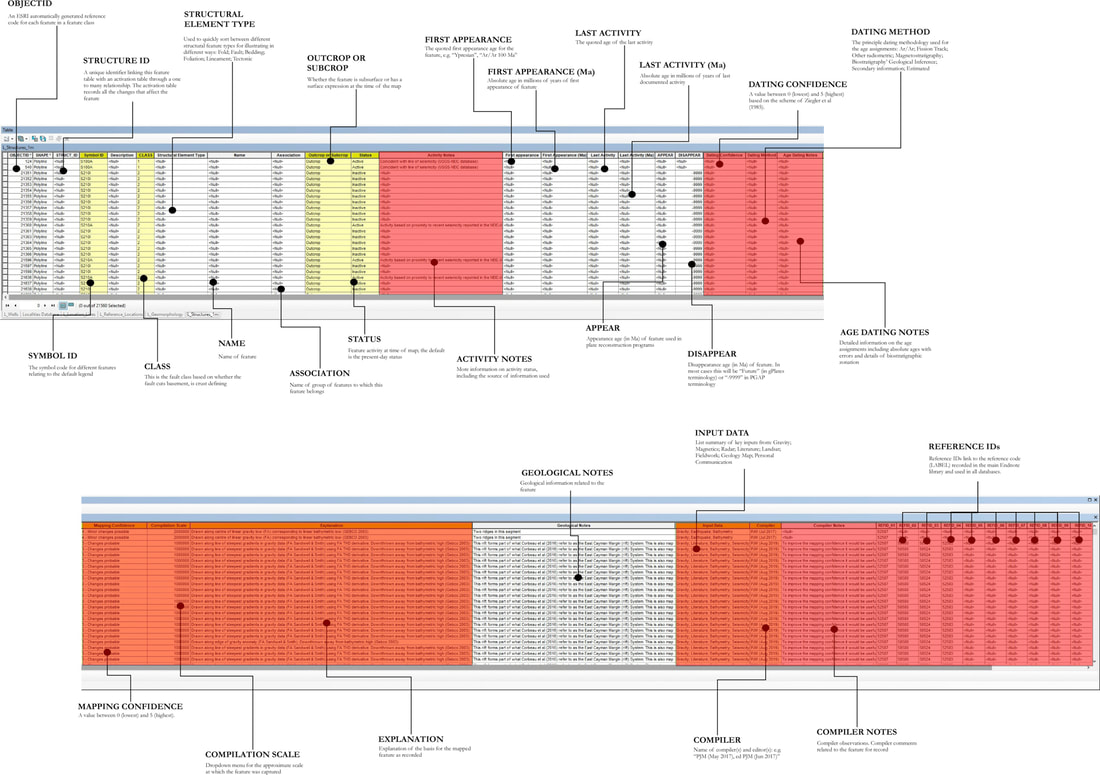

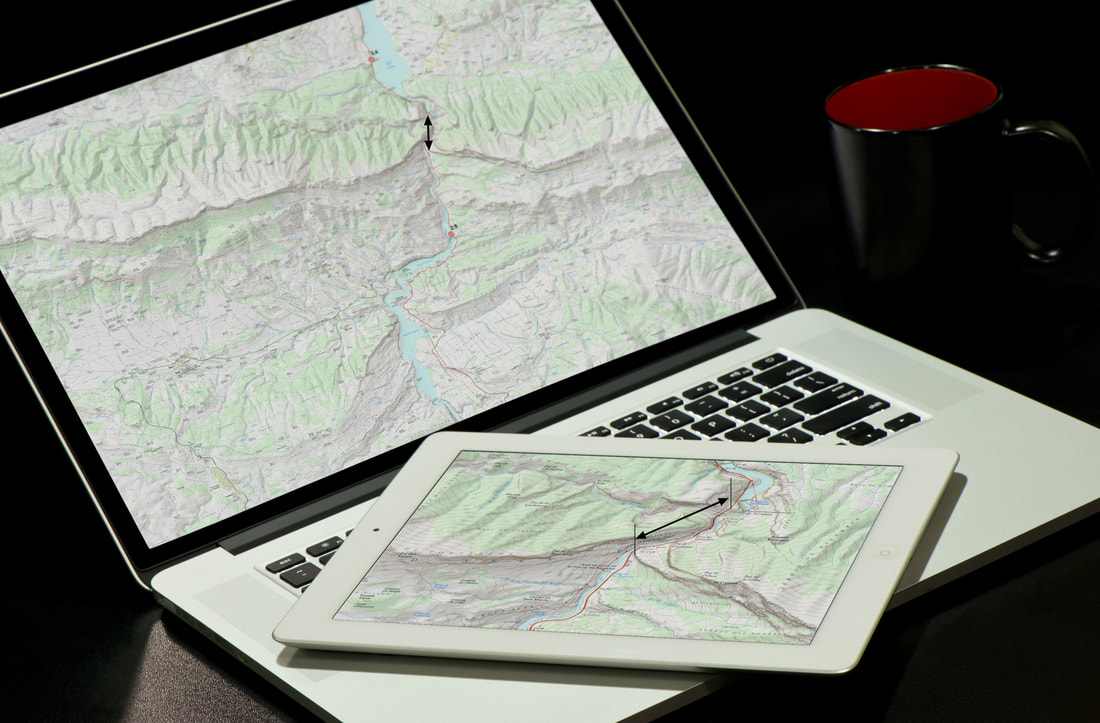

(For further information on this see Markwick & Lupia (2002) Providing the answers to these questions will enable anyone using the database to replicate what was done and to make decisions on how they use the data. Where this applies to the database as a whole it will be recorded within the metadata. The metadata also provides information on the intrinsic characteristics of the data in a database, such as data type, field size, date created, etc. This is different from extrinsic information, such as the input data used for a specific database record. This extrinsic, record specific information is stored within the data tables themselves. For example, in our Structural Elements Database (see figure 3 attribute table), features may be based on an interpretation of one of several primary datasets, including Landsat imagery, radar data, gravity, magnetics, and seismic. This needs to be recorded because each primary dataset will have its inherent resolution and errors. I have always believed that more explanation is required. So, within my own commercial and research databases, I have added text fields for each major inputs to describe the basis of each interpretation. For example, an “Explanation” field provides a place for describing exactly how a spatial feature was defined. All records are then linked to a reference library through unique identifiers (Markwick, 1996; Markwick and Lupia, 2002). This is a relatively standard design. (Nb. In my research, I use the Endnote software, which I have used since my Ph.D. days in Chicago in the 1990s and which I can highly recommend https://endnote.com/) Figure 3. The main attribute table for the Structural Elements database showing in red those fields used to qualify and/or audit each record. Of 38 fields 20 store information that qualifies the entry. In addition, there is the metadata, data documentation, and underlying data management system and workflows. The problem for database design is knowing what level of auditing is needed to adequately qualify an individual record. This will depend on whether the record is of a primary observation – analytical, field measurement, etc – or an interpretation. Interpretations can change with time. For example, a biostratigraphic zonation used 30 years ago may not be valid today, but the primary observations of which organisms are present may still be true (accepting that taxonomic assignments may also change). So in a database of this information, you would need to record not just the zonation (interpretation), but also what it was based on – this might either be a complete list of the organisms present (the approach I took with my Ph.D. databases) or simply a link to the reference which contains that information. Another example that has driven me to frustration over the years is the use of biomarkers in organic geochemistry. Interpretations of these have changed frequently over the last 40 years. For example, the significance of gammacerane (the gammacerane index) which I remember in the 1980s as an indicator of salinity (Philp and Lewis, 1987), but which may (also) indicate water stratification (Damsté et al., 1995), or water stratification resulting from hypersalinity (Peters, Walters and Moldowan, 2007), or none of the above. In both of these examples, we have an analytic error – misidentification of a species down a microscope or errors associated with gas chromography (GC), or GC-mass spectrometry (MS), etc – and an error or uncertainty in the interpretation. In any database, we, therefore, need first to ensure that we differentiate between the two: observation and interpretation. We then need to record auditing information that covers both: what the biomarker is (observation); the analytic error in the observation; the interpretation; a reference to who made the interpretation, when, and why. To which we can add a comments field and a semi-quantitative confidence assignment by the person entering the data into the database (see below). By recording the reference of the interpretation and analysis we can then either parse the data to include or reject it for specific tasks or update the interpretation with the latest ideas. Again, this would be attributed as an update or edit in the database and audited accordingly (in my databases I have a “Compiler” field that lists the initials of the editor and month and year when they made any changes – in corporate databases you may need to have more detail than this). We need to keep track of all these things in a database if the database is to have longevity and application. This is not easy. The consequence is that within a database we end up with most of the fields being about auditing our data, rather than values or interpretation (Figure 3). Scale, Resolution, Grain, and Extent in Digital Spatial Databases In spatial databases we also need to understand scale and resolution. We all ‘know’ what we mean by “map scale”. It is something that is always explicitly stated on a printed, paper map and provides an indication of the level of accuracy and precision we can expect (not always true but our working assumption). But digital maps are a problem. Why? To answer that, ask yourself a simple question “what is the map scale of a digital map?” To understand this question, open up a map image on your laptop or phone and then zoom in. Is the scale the same before and after you zoom? – measure the distance on the screen! The answer is of course “No”. The map image may have a scale written on it, but on the screen, you can zoom in and out as far as you want (Figure 4). This immediately creates a problem of precision and accuracy (see below). How far can we zoom into a digital map before we go beyond the precision and accuracy that the cartographer intended? In building digital spatial databases we can address this in one of several ways

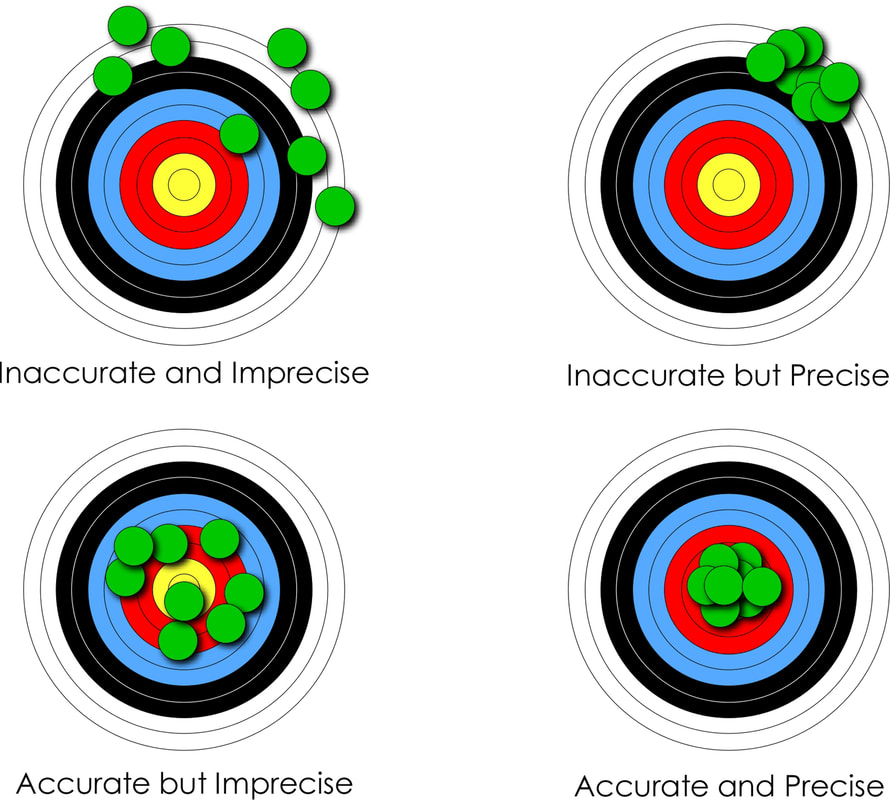

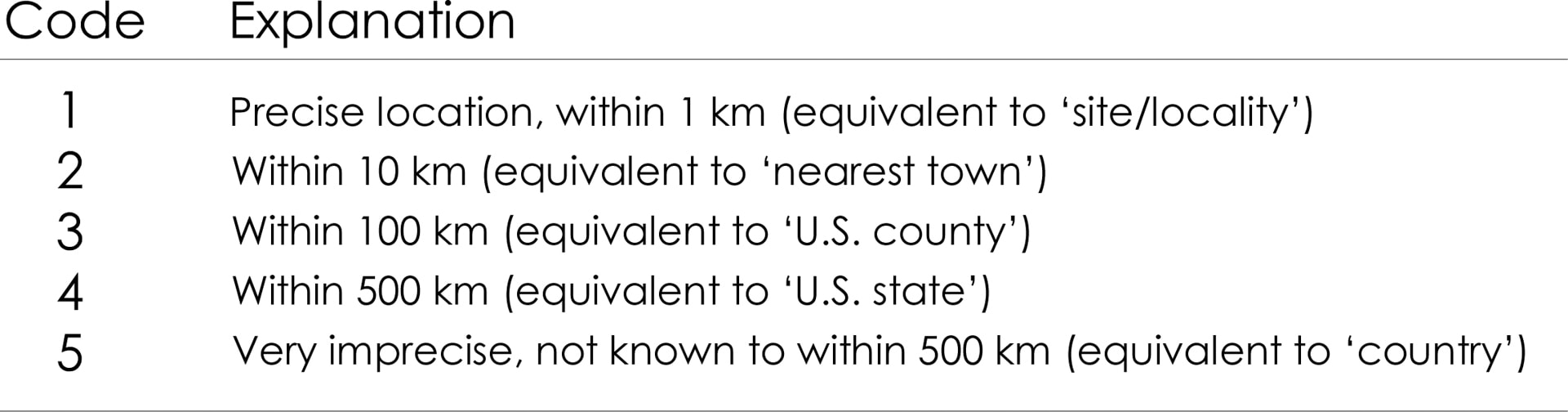

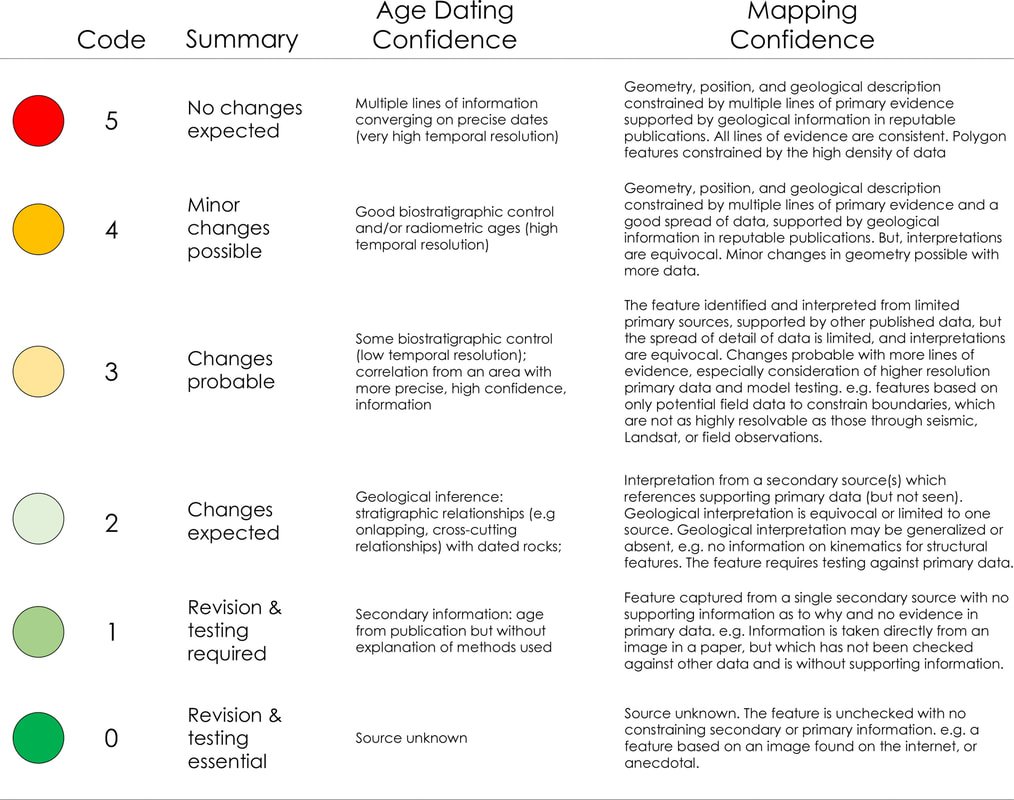

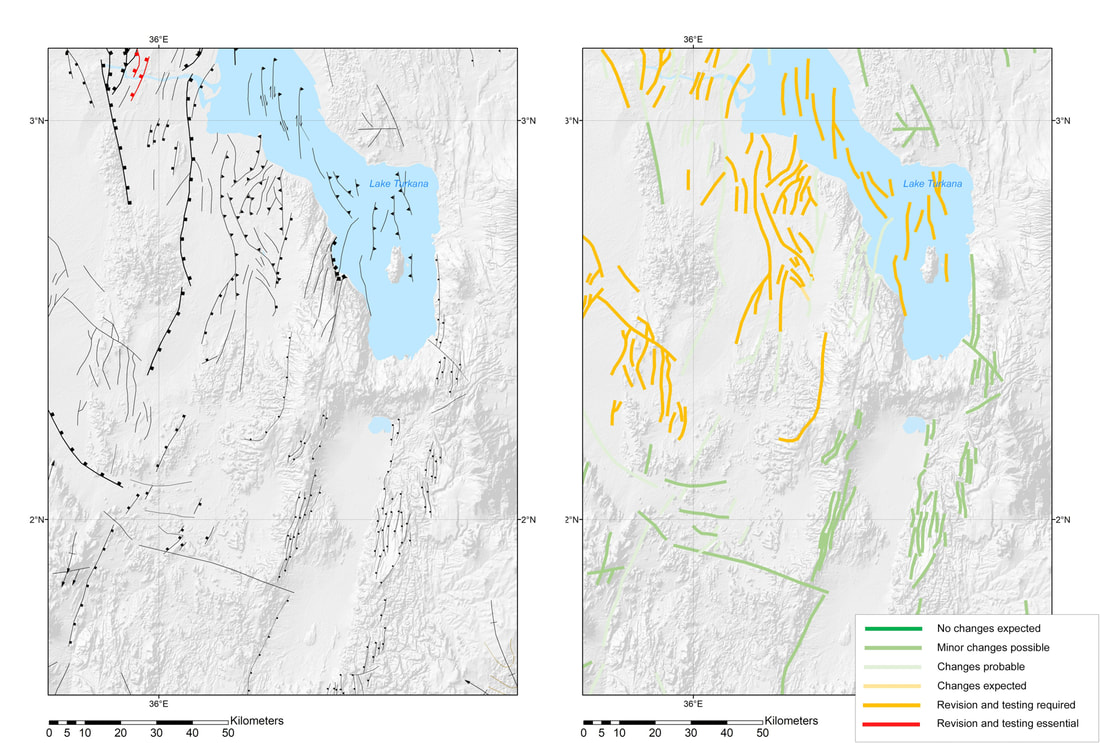

As with all data issues, the importance is being aware there is a potential problem here. Two further terms you may find of use when thinking of spatial data are “grain” and “extent”. These are both adopted from landscape ecology. Grain refers to the minimum resolution of observation, for example, its spatial or temporal resolution (Markwick and Lupia, 2002). Extent is the total amount of space or time observed, usually defined as the maximum size of the study area (O'Neill and King, 1998). So, a large scale map may be fine-grained but of limited extent. The key is specifying this for each study. Figure 4. The same 1:25,000 scale map shown on two different devices but at two different ‘scales’. The tablet shows a zoomed in view – the arrows show the same transect in each case. In neither case are they are 1:25,000. Map source; 1:25,000 topographic maps of Catalonia – this an excellent resource available online Precision and Accuracy Differentiating between precision and accuracy is something of a cliché (see Figure 5). But no less important. A geological observation has a definite location, although it is not always possible to know this with precision, either because the details are/were not reported, or the location was not well constrained originally. Today, with GPS (Global Positioning Systems), problems with location have been mitigated, but not eliminated. For point data, this can be constrained in a database by an attribute that provides an indication of spatial precision. In my databases, this is a field called “Geographic Precision” (Table 1). The precision of lines and polygons can be attributed in a similar way, although in our databases we have used a qualitative mapping confidence attribute which implicitly includes feature precision and accuracy (see below). Temporal precision and accuracy are more difficult to constrain in geological datasets. Ages can be made incorrectly, be based on poorly constrained fossil data, or radiometric data with large error bars. In some cases, there may be no direct age information at all, and the temporal position is based on geological inference. Ziegler et al (1985) qualified age assignments based on their provenance, which we have also adopted. Figure 5. A graphical representation of the difference between accuracy and precision. This is something of a cliché but important to understand nonetheless Table 1 - Geographic precision. This is a simple numerical code that relates the precision with which a point location is known on a map. This allows poorly resolved data to be added to the database when no other data is available, which can be replaced when better location information is known (Markwick, 1996; Markwick and Lupia, 2002). Well data should always be of the highest precision, and indeed should be known within meters Qualifying and quantifying confidence and uncertainty Whilst analytical error is numeric, and sometimes we can assign quantitative values to position or time (± kilometers, meters, millions of years) this is not always possible. So another way to approach the challenge of recording confidence or uncertainty is to have the compiler assign a qualitative or semi-quantitative assessment. In our databases, we again follow some of the ideas outlined in Ziegler et al., (1985), Markwick and Lupia (2001), Markwick (1996). These schemes are distinct from quoted analytical errors and are designed to give the user an easy-to-use ‘indication’ of uncertainty (Table 2). Table 2. Explanation of confidence codes used for structural elements. The age dating confidence is based on the scheme described in Ziegler et al (1985) The advantage of this approach is that it is simple, which encourages adoption. The disadvantage is that even with explanations of what each code represents (Table 2), there will be some user variation. Nonetheless, it provides an immediate indication of what the compiler believes, which can then be further explained in associated comments fields. In map view, colors can be applied to give the users an immediate visualization of mapping or dating or other confidence depending on what the user needs to know. An example of the mapping confidence applied to structural elements is shown in figure 6. Confidence is further expressed visually using shading, dashed symbology, and line weighting (this is discussed in our database documentation and will be the focus of an article I am writing on drawing maps). Figure 6 - A detailed view of the eastern branch of the East African Rift System in the neighborhood of Lake Turkana showing the structural elements from our global Structural Elements database (left) colored according to the assigned mapping confidence (right). The lower confidence assigned to features in the South Sudanese Cretaceous basins (just outside this extent) reflects the use of published maps as the source to constrain features. Although these interpretations may be quoted as based on seismic, as they are, the lack of supporting primary data relegates the confidence to category 2 or in some cases 1. Those upgraded to category 3, indicated by the light green colors, are supported by interpretations from primary sources, such as gravity or better quality seismic. The category 4 features (medium green) in this view are largely based on Landsat imagery constrained by other sources, such as high-resolution aeromagnetic data and seismicity. This gives the user an immediate indication of mapping confidence, which intentionally errs on the side of caution. Features can be upgraded as more data comes available Do we capture all information? By including fields for record confidence means that the database can be sorted (parsed) for good and bad ‘quality’ data. Why is this important? Why not do this on data entry? You could, for example (and I know researchers who do this) make an a priori decision and remove all data that you believe is poor and not include this in the database. But what if this ‘poor’ datum is the only datum for that area or of that type of data that you have? For example, in a spatial database, we may have a poorly constrained data point for a basin (we know its location to within 100 km, but no better), but no other data. That data point is then important or could be, but is spatially poorly constrained – in this case, a low spatial precision. We need to include this record in our database, because it is all we have. But we need to ensure that the record is audited to reflect the uncertainty in its location. A priori decisions on which data to include in our database based on an initial assessment of data confidence are therefore to be avoided:

Who are the database builders? Given how much information we need to record to qualify our data, it will come as no surprise that data entry compliance is a major difficulty. Database population is very tedious. This can result in errors, or short-cuts being taken, or worse. As an example of what can happen, I had one senior geologist, who will remain nameless, point-blank refuse to attribute his interpretations, stating that GIS and attribution “were beneath him”. After pressure, he acquiesced. But during my QC stage, I found that in a fit of pique he had copied and pasted the same attribution for all records – assigning “Landsat imagery” as the source for submarine features was a bit of a giveaway! All of his work had to be redone, by me as it happened… This case highlights a serious challenge, to get staff to realize the importance of the audit trail and to fill in these fields. From my experience let me suggest four ways you can do this (other than threats):

The solution here is to recognize that technology is there to help you reach answers by removing the most tedious repetitive tasks, and analyzing and managing large datasets. But we must never forget that we still need to know our data. It is a truism that the more remote we get from our data the least likely we are to understand any answers our AI system gives us. We also need to remember that databases are ‘living’ in the sense that you cannot, should not simply populate a database and walk away, but recognize that you need to update and add to your database as more information becomes available. It is about knowing your data There is no question that AI and machine learning have much to offer us in data science. But where I worry a little, or perhaps more than a little, about AI is how it is being perceived in many companies as a black-box solution to the problem of big data. We as users need to have enough knowledge to understand the answers such systems give us, but more importantly, as I hope I have demonstrated here in this brief introduction, we need to ensure that we know where our data has come from and that we trust it. This is not just in the sense of computer verification, but in constraining the nature of the original data itself, how it is recorded, how confident we can be with this recording. This process of qualifying and auditing data is admittedly laborious as my examples of solutions show, but I hope you will have seen how powerful even the simplest schemes can be when used systematically. A pdf version of this blog is available here for download. Postscript As some of the more observant readers will have noticed the sediment in the picture at the beginning of this article is not clay, but sand. As I have emphasized throughout, you need to know your data – be careful what you build from References cited Callegaro, M. & Yang, Y. 2018. 23. The role of surveys in the era of "Big Data". In The Palgrave Handbook of Survey Research eds D. L. Vannette and J. A. Krosnick). pp. 175-91.

Damsté, J. S. S., Kenig, F., Koopmans, M. P., Köster, J., Schouten, S., Hayes, J. M. & Leeuw, J. W. d. 1995. Evidence for gammacerane as an indicator of water column stratification. Geochemica et Cosmochimica Acta 59, 1895-900. Markwick, P. J. 1996. Late Cretaceous to Pleistocene climates: nature of the transition from a 'hot-house' to an 'ice-house' world. In Geophysical Sciences p. 1197. Chicago: The University of Chicago. Markwick, P. J. & Lupia, R. 2002. Palaeontological databases for palaeobiogeography, palaeoecology and biodiversity: a question of scale. In Palaeobiogeography and biodiversity change: a comparison of the Ordovician and Mesozoic-Cenozoic radiations eds J. A. Crame and A. W. Owen). pp. 169-74. London: Geological Society, London. O'Neill, R. V. & King, A. W. 1998. Homage to St. Michael or why are there so many books on scale? In Ecological Scale, Theory and Applications eds D. L. Peterson and V. T. Parker). pp. 3-15. New York: Columbia University Press. Peters, K. E., Walters, C. C. & Moldowan, J. M. 2007. The biomarker guide. Volume 2. Biomarkers and isotopes in petroleum systems and Earth history, 2nd ed.: Cambridge University Press, 704 pp. Philp, R. P. & Lewis, C. A. 1987. Organic geochemistry of biomarkers. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 15, 363-95. Samuel, A. 1959. Some Studies in Machine Learning Using the Game of Checkers. IBM Journal of Research and Development 3, 211-29. Ziegler, A. M., Rowley, D. B., Lottes, A. L., Sahagian, D. L., Hulver, M. L. & Gierlowski, T. C. 1985. Paleogeographic interpretation: with an example from the Mid-Cretaceous. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 13, 385-425.

0 Comments

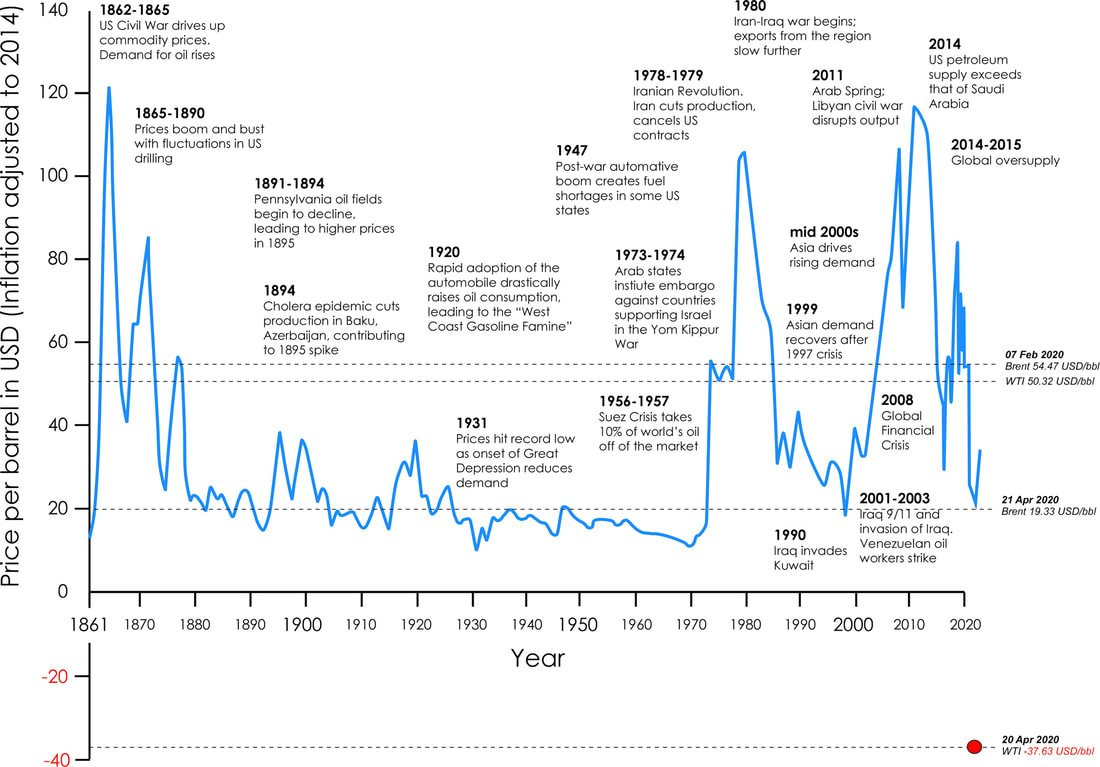

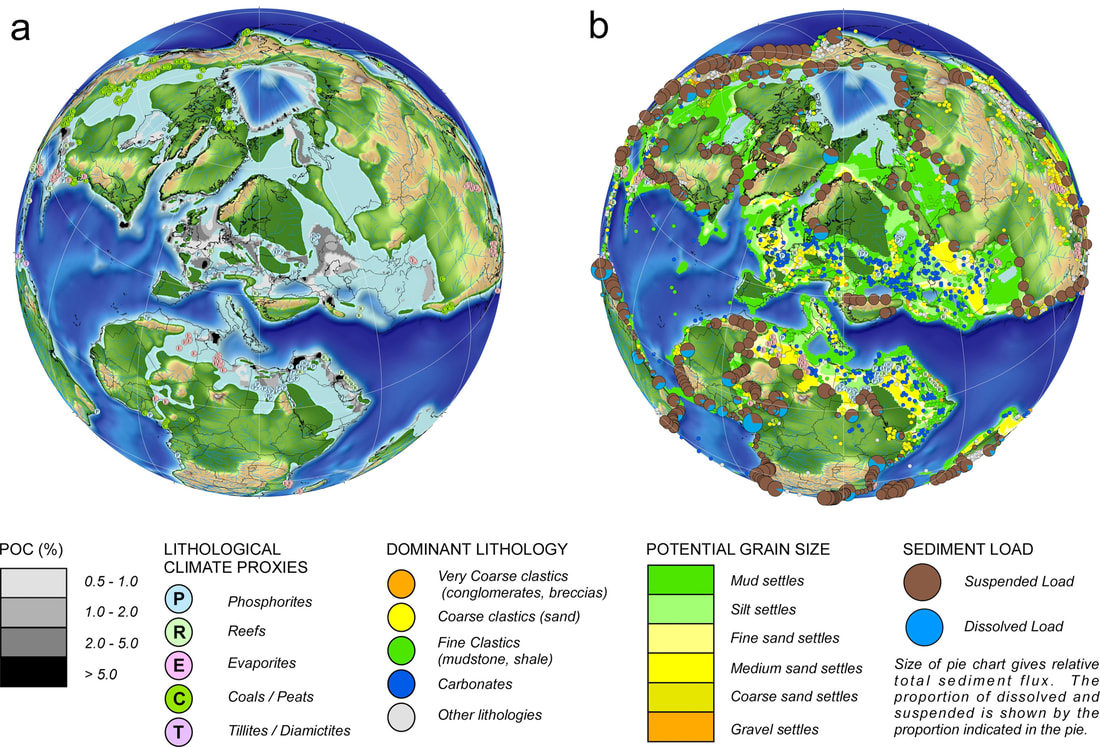

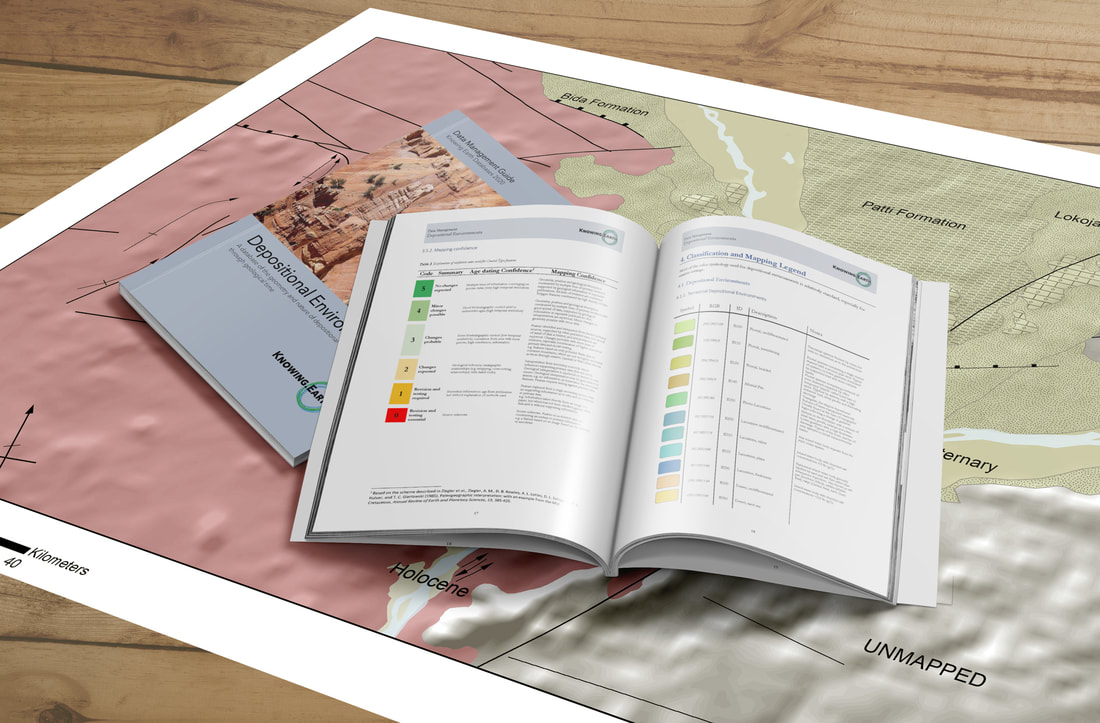

“Alexanders is closed” What next for exploration? I thought I was being very organized last winter as I built up a portfolio of blogs and articles to provide myself with materials to post during 2020. What a great idea! Planned commercial projects were coming in and I knew that these would take up much of my time. Even as news of the epidemic filtered out of China in January, there was a sense that this was to be a repeat of SARS. But as I got ready to post today’s article at the end of February, the news from northern Italy showed all too clearly that this coronavirus had spread beyond China and that this was not going to follow the geographic limits of its predecessor SARS. It is ironic, that this blog is about a changing exploration industry. And now five months later, everything has changed. But in re-reading what I wrote I believe it is still a relevant discussion. So... Houston: Cowboys, oil, alligators, and steak… A world that has gone? Should go? Or is it just on hold? Your answer will depend on your politics and vision of the future. Whatever your view, the world is certainly changing, and that change needs to be managed. So, what next? Or do we just wait and see what happens? That might work for some… in the swamp… The sign on the door was clear, “Alexanders is closed”. It was April 2017 and after 10 hours on an economy flight from London, it was not what I wanted to see. But the reality was there for all to read. Alexander's restaurant (http://jalexanders.com) at the corner of Westheimer and Wilcrest had long been my refuge. It had been there for as long as I had been visiting Houston. First as Houstons then as Alexanders. A place to relax and think, to meet with friends, enjoy a steak after a long flight or a days’ meetings. My usual dilemma was whether to go for their ‘famous’ baby back ribs or the filet mignon with a béarnaise sauce. Then there was their “vegetable of the day” of which the sautéed spinach, creamed spinach, grilled zucchini, and beefsteak tomatoes are, or rather were, worthy of note. The baked potato fully loaded was usually a step too far as I saved myself for their wonderful carrot cake. So moist. So bad... And now it was gone… Whilst for many of you the closure of Alexanders is completely inconsequential, especially now, and indeed most of you have probably never heard of Alexanders, for me, it was yet more evidence of changing times and the loss of reassuring certainties. Little did I know… This graph is based on that shown on the World Economic Forum website in 2016 https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/12/155-years-of-oil-prices-in-one-chart/) modified to include more recent changes (from Bloomberg). The original version of the graph is cited as Goldman Sachs (see additional references on the weforum page). The fluctuations in prices are clear, especially over the last 40 years There are cycles and there are cycles... The oil and gas industry has always been cyclic and many of us have seen many - far too many - downturns and recoveries. Indeed, many old-timers seem to keep track of their careers by the number of downturns they have seen and survived. Each recovery in the past has seen an increase in budgets and a major hiring drive, as business returned to 'normal'. But the last downturn has been different, starting in 2014, and now exacerbated by the consequences of COVID-19. Yes, we as an industry are faced by many challenges, not least the transition from fossil fuels to a more diversified energy portfolio, the vagaries of unconventionals or the political game playing between the worlds leading oil producing countries. Each deserves a blog in its own right. But the change that concerns me the most, and which I think will have the biggest ramifications not only for our industry but for Earth education in general, is the loss of experience. The Alamo, San Antonio. A metaphor for our industry? No. Changing demographics: the good, the bad, and the seriously worrying… As I walked around last year’s AAPG convention in San Antonio I was struck by the greater number of young geologists and the broader diversity of attendees than in previous years. This was great to see. Change is happening and it is no bad thing. But with all the new faces there was also the demonstrable absence of old faces and with that experience and expertise. it is true that each past downturn has resulted in a gap or pause in the staff demographics as potential graduates looked at what was happening and opted for different careers. The resulting demographic imbalance has been long recognized, and many, if not most companies were actively addressing this through mentoring, knowledge transfer, and digital knowledge and database systems. But the depth and extent of this last downturn have left this process of knowledge transfer incomplete. More significantly, it has seen a generation of experience opt for early retirement and a younger generation who are increasingly deciding against the Earth sciences. This has been compounded by a general reticence to hire significantly this time given uncertainty over the future. The question is, have we lost so much of our experience in this last downturn that this will affect our recovery as an industry and especially our ability to brainstorm and solve the challenges that now face us? An industry of the brightest scientists and engineers… Our industry can boast some of the brightest scientists and engineers of the 20th and 21st centuries. We have been at the forefront of increasing the understanding of our planet from tectonics, to depositional processes to paleontology and beyond. Our industry has developed and build technologies and tools that can send sound waves into the Earth to resolve the structure of the subsurface even down to the Moho (the base of the crust) and can now drill through kilometers of rock from rigs sited in two kilometers of water and still know where the drill head is within meters. That is quite incredible. Well, I am still impressed This is something that we should be extremely proud of. Achievements that we should shout about far more than we do. The new generation is equally gifted, if not more so. I have been lucky to hire and work with many excellent young geologists. But they would be even better with mentoring from and access to experienced staff. But those experienced staff have either left or are about to leave the Industry. (As I was about to post this article, I received an e-mail from a friend in Houston who had just announced that she was leaving the Industry. Carmen is one of the most impressive scientists I have worked with and a great role model for the next generation and especially the growing number of young women joining the industry. Her departure is a devastating loss and one the Industry can ill-afford). Experience is key! This is all the more important as we apply our industry’s skill-base to energy transition and building new business models. Experience is about having seen numerous real-world examples and being able to draw on these when making decisions, warts, and all. Knowing what worked, what failed, and why. As my Ph.D. advisor repeatedly told me "the best geologists are those who have seen the most rocks". (I am convinced that this is something said by every Ph.D. advisor to every geology Ph.D. student, but that makes it no less true). And that places us in something of a cleft stick. On the one hand, the Industry is addressing past diversity issues and hiring a new generation of enthusiastic, talented, Earth scientists, albeit in limited numbers. Whilst simultaneously cutting costs. Great… But, on the other hand, we have lost the experience and expertise we need to both mentor the next generation and also to make informed decisions as we start to explore once more. So, what to do? Let me respectfully offer a few suggestions: 1. Make more from what you have Today companies have libraries filled with 3rd party reports, internal studies, presentations, and databases. That is an incredibly powerful resource, but only if used. The challenge is to understand what you have and how to integrate this within your current workflows. What data and knowledge are good? What is bad? What can you accept and what should you ignore? It is certainly advantageous to know where the skeletons are before you repeat past mistakes! Mistakes cost time and monies. Why spend more monies if you already have the answers, or resources to get to the answers, in-house? An easy win is to get your libraries curated and databased. In some companies, this has already been done. It is something I spent 2019 doing with my libraries (see my blog on scanning) Another solution is to bring in the original product builders and get them to explain what they did and where useful, updating their products to fit new corporate workflows. This is certainly where much of my time would have been focussed this year (until some errant RNA intervened), having spent the last 25 years designing, building, and selling products and solutions to exploration companies. One problem with seeking out the builders is that whilst their companies may still exist (possibly) the authors themselves may have moved on. The same is true when looking for your own staff who made the original purchases with a specific plan in mind and/or who used the products. You may need to visit the golf courses of Houston or drive out to the Hill Country (though obviously not Alexanders) – ‘social distancing’ notwithstanding. Many of you may have access to the excellent global resources that are now available. I was privileged to be instrumental in the development of several of these, working and building some great teams. The challenge, as an exploration group, is how to get more from these. They each have their own strengths, and each was designed for slightly different purposes. What do you need to know to unleash their potential? Feel free to drop me a line. This image is based on my 2019 paper and 30 years of research and experience 2. Strengthen relationships with University research groups University research groups have always been a great source of cutting-edge ideas, knowledge, understanding, and data. Not to mention future staff. With down-sizing and the disappearance of company-based research groups, universities are becoming all the more important. This is not just about bringing in a professor to give a one-off seminar, but from my experience is best achieved through more active participation through workshops, having academics work directly with teams, and through MSc and Ph.D. projects and internships. As an example, last year I participated in a week-long workshop for a company that convened leading academics from different research groups and with varying opinions. In a few days, staff were exposed to all the views and background from the leaders in the field, something that would have taken them months to get a handle on by only reading their papers, and which even then, would not have provided the insights into the mindsets of the protagonists. (There is also a need to maintain a presence in Academia at a time when our industry is increasingly perceived negatively). 3. Go back to the basics. Get out the pencil crayons. Get your young staff to look at paper copies of seismic and use colored pencils to identify horizons. The key is to encourage your teams to understand the data, know their data, and to ask questions. They should not be afraid to disagree with their elders, but wise enough to know that experience can be an advantage. We are not infallible, but we have seen more rocks and solved more problems. 4. Understand the whole system, what to ask, who to ask and where to find solutions. With fewer staff and the disappearance of the armies of specialists we used to have, it is key that the next generation knows how the Earth system fits together. This does not mean going all "fruit salad" (my thanks again to Catherine for that wonderful imagery), in which our staff have a little bit of knowledge of everything but no real depth. This is about ensuring that our teams know the vocabulary and key headlines of diverse scientific fields and most importantly that they know enough to be able to ask the right questions and know whom to ask or where to search for the answers. A picture I have used many times, but no less relevant for its repetition. When we consider any problem to do with the Earth system, whether in exploration or environmental change, we have so many components to think about. There is simply so much to take in! Where do we start 5. Do not assume that technology will solve everything… Over the last three years, advances in machine learning and AI have been impressive. Pattern recognition has indeed been around for many decades: auto-trace in seismic interpretation, or computerized fossil recognition in biostratigraphy. The limitation in the past was largely computer processing power, which is no longer such an issue. With data storage now relatively cheap, and especially the development of cloud storage, accessing data and knowledge from anywhere in the world should be child’s play. The problem is that whilst a child can operate an iPad with ease from kindergarten on, if not before, and they are incredibly computer savvy, they do not necessarily know the questions to ask. That comes with experience and does not seem to be always taught. As evidence ask them to do a Google search and see what they find; I am always amazed at what people do not find. Technology is wonderful, and I am a self-confessed addict having designed, built, managed and analysed computer-based databases for over 30 years. But don't forget the basics - ask questions, know your data, question everything. Operationally what should we do? Well that is your call, but let me suggest the following:

I have spent much of my career designing, building, and managing large, global databases. Key to their success is knowing where the data has come from, what can be used, and what should be thrown the trash or used with caution. There is a fundamental difference between data and verified data. One is a collection of words and numbers, the other is power. So, where next? The future is about preparing our new generations of Earth scientists with all that we have learned over the last century or more, what worked, what failed, and why. To know the questions to ask and where and how to find the answers. The next generation of Earth scientists needs to be well-grounded in the fundamentals of geology and the scientific method. At the same time, they need to be conversant with a broad range of scientific fields, or at least enough to know the vocabulary of diverse fields and how each discipline might impact the problem they are trying to solve. This also gives them transferrable skills that will aid the energy industry as we transition to alternative sources of energy, but also enable them to look at applying their expertise and experience to a range of other challenges, from the management of water resources to carbon capture, and storage (CCS), to geothermal energy, mineral exploration and waste management. They need to be familiar with the tools available, but not to assume they these will solve all the problems they find. At the end of the day, we need to harness all that we have learned in our industry to accelerate the next generation in understanding even more than we do for the betterment of mankind. Understanding the Earth is what we do! Epilogue. What happened to Alexanders? A search on the internet revealed that Alexanders Westchase closed at the end of January 2017 on the very same day that I had left my role as Technical Director of an Aim-listed consultancy after 12 years of successfully building the business. Coincidence I am sure…Rule #39 notwithstanding.. Today, what was once Alexanders in Westchase, Houston, is the site of a 24-hour emergency center. Useful and admirable, especially right now. Though I won't be going there for steak "Alexanders is closed". All change. Useful and admirable, but not quite the dining experience I was expecting. Image from Google Streetview. What would we do without Google? A pdf version of this blog is available here for download

Business ‘success’ very much depends on your measure of ‘success’. For some people that measure might be making large profits or growing the market value of their company. For others, it may be the physical size of their business in terms of the number of staff or offices. Whilst for others success is about being recognized for the quality of their services and products. Whichever of these metrics you chose defines your business’s culture and values and is largely dictated by the CEO. There are numerous websites with business tips for success. Most are useful. But, which one is most appropriate for your business will depend on the industry you are in and what is important to you personally. Below are my recommendations for success based on over 30 years’ experience in the oil and gas industry and over 10 years as an executive director of a highly successful, AIM-listed natural resources service company based in the UK. Although my experience has been with running knowledge-based companies, with their dependence on translating creativity, ideas, and scientific excellence into income, most of the lessons I have learned may be applied to all businesses. I hope you find this of use. 1. Be passionate about what you do To be successful you need to be passionate about what you do. You need to care about your business, what it produces and what it stands for. This means having a vision for what you want to achieve and how it will change the world. Once you stop caring about what you do, and your company becomes “9 to 5”, then it is time leave and do something different. It is true that passionate leaders can be difficult to work with. An often-quoted example is the late Steve Jobs. Brilliant, driven and, by most accounts a pain in the butt to work with. But he changed the way we work and communicate, created some of the most beautiful and desirable products ever conceived, whilst simultaneous building the most valuable company in the world from the seemingly inescapable mire of the Macbook 5300 in the mid-1990s (I had one, I know how bad it got...). Can you be passionate without being an a**e? Of course, you can. 2. Make sure you have the right team Having the right team is critical. If you don’t then you will find yourself spending too much time worrying about what they are doing, running around retrospectively cleaning up ‘their’ mess and not having time to do what is important. As an executive, this is totally in your hands. You are the one in control of hiring. Or, at least, you should be. If you are not, then either change this or get out quickly. If the person you are interviewing does not meet your criteria, or you are not sure they do, then recast the net and look for someone who does. In my experience you are far better off having a small team of like-minded, passionate people, then a big team of not so right people working 9 to 5. Once you have the right team then you need to keep them. How you do this will depend on the individuals concerned. You will need to ensure you understand their needs and ambitions. If not, you will lose them. But be prepared. Even the best team’s break-up eventually. 3. Know what you believe What is your story? Why are you doing this? Mission statements have become something of a “must-have” for all companies. Sadly, a quick search online would suggest that most mission statements come from the same source and I do wonder if there is an automatic mission statement generator out here. This is a shame, because if all the companies truly believed in what they stated they believed in, then the world would be a much better place. Personally, I would find it refreshing if companies included their real missions: “The mission of company X is to make heaps of cash, whatever it takes”. That has the appeal of honesty and transparency, whilst also being quite disturbing to my liberal, albeit globalist, capitalist sensitivities. Yes, you can be a liberal-minded capitalist! It comes down to what we, as individuals believe, and how we then communicate this to our staff and our company. This is not easy. Perhaps the first question to ask is why do some of us work 24/7 for a business?

In most cases, it is because we love what we do, and we want the business to be successful, and for some of us because we have broader ambitions to change the world and make it better for future generations. For me, the ‘best’ companies are those who strive to change the world we live in. Either at the day-to-day scale of providing a great service or environment, such as a wonderful evening at your favorite restaurant. Or the more grandiose ambitions such as those of Google, with their (possibly anecdotal) aim of making “all knowledge one click away” (although I now find this has changed as you will see from the link), or the original Body Shop, set up the late Anita Roddick and its concern for animal welfare (no animal testing). The mission statement I like best, because the company follows up on what it says, is that of the outdoor clothing company Patagonia, “Build the best product, cause no unnecessary harm, use business to inspire and implement solutions to the environmental crisis”. What your ambition is will affect what business you establish as well as its mission statement. If, on the other hand, your ambition is simply to climb as high and as fast up the corporate ladder as you can, grabbing as many monies and perceived attention on the way as possible, then frankly which type of company you manage is completely immaterial. Though I can assure you, it will not be one of mine. 4. Understand your business Being passionate about what you do is critical, but if you are going to make a success of your business, you also need to understand what that business is. This may seem like a 'no-brainer', but there are too many examples of senior management brought into companies to 'save them' or take the company 'to the next level', who simply have no idea of the business they are trying to save. The best way to be sure of your business story is to make this as succinct as possible. The most commonly used approached, and the one I like is to use, is the "elevator pitch" where you have 2 minutes and 10 floors in which to explain to someone what your business is and does and why they should call you. A cliché? Absolutely. Good advice? You bet. 5. Understand your clients There are few companies that can dictate to their clients what they, the clients, want and get away with it. Apple is, again, probably the stand-out exception. Most companies respond to their clients, they are reactive. This is not necessarily bad, but it can mean that you are constantly playing catch-up as client needs change. This is increasingly true in the modern age of mass communication and social media with its immediacy and ever-accelerating change. To make this work you need to understand both your own business and products (it is rather difficult to know how you can help your clients if you don’t know your own business) as well as that of your clients. In knowledge-based consultancy, this is about doing your homework on the background to a problem that might affect a particular client. But it is also about being competent and trusted enough by your client to be able to provide them with advice and guidance when they don't know what they want and need. To get to this point nothing beats face-to-face meetings, especially brainstorming sessions to define the problem and identify potential solutions. 6. Play to your strengths One of my longstanding clients reiterated to me at almost every meeting over 20 years to “play to your strengths”. Of course, this was as much about what they needed than a piece of business advice. Companies need to trust their service providers, especially large organizations for whom switching to a new provider is extremely difficult. As a business, you need to be known and trusted for something that clients can put their finger on. You need to be an expert in a particular field or provide a service you are renowned for. This may seem contrary to the need for “flexibility” which features highly in most top 10 lists. Flexibility is certainly important (though not in my top 10). But for many companies talk of “flexibility” can really be a cover for “flakiness” and a lack of a strategic direction. Once you have an established strength, then you can think about diversifying if that is your strategy. 7. Trust and relationships are important Another cliché, but true none the less: business is about trust and relationships. I recall a meeting in Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) with one of the oil majors to whom I was trying to sell a particular scientific report. Well, I gave a presentation, got chatting and, as usual, I got carried away with the science. At the end of the meeting, I asked if they had all the information they needed. To which I was greeted with big smiles. I had indeed… Sales is always that balance about being excited about the product and what it contains and not giving away the answers so that the client doesn’t need to buy the product… What happened in this case? Well, the company bought the report, and then bought more and became one of our best clients. Why? Because they knew that when they needed to chat with an expert to get answers hey could trust they only needed to call. Relationships and trust take years to build but can take only moments to destroy. Whatever you do, don't intentionally destroy relationships. I have seen this happen and it is insane. If you are retreating (moving away from a particular business line or sector, for whatever reason), be very sure that the bridges you are burning may not be useful in the future when fortunes change, and you are on the advance. 8. Don't run out of cash Most companies that fail do so because they simply run out of cash. This need not reflect a lack of 'success', nor the lack of a strong order book, but more the case that you probably should have changed your Finance Director. It is about managing one input, revenue, and one output, costs. For most knowledge-based companies, the biggest costs are staff, which is why it is so important to have the right team around you. You need to have control of both sides of this equation. Revenue comes back to knowing your customers and cost comes down to then building the right products and doing so efficiently 9. Be organized Being organized as a business includes both how the company is structured to how the business is run operationally - how you build your products (project management and workflows) and manage your data and knowledge (data management). These are inter-related and will directly impact your cost-base. Keep your management structure simple, with few levels as possible. This will vary by business, but in knowledge-based consultancy remaining "hands-on" is often critical, since access to your most senior, experienced team members is what your clients expect and what they are paying for. You then need the right staff around you, a good lieutenant you can trust, and good support staff. Operationally, you need to implement a clear project management system. Everyone needs to know what they are doing, why they are doing it and how to do it. Getting this right is surprisingly difficult. Most project management websites advocate getting everyone's input and 'buy-in' on project and management systems. This is great in theory but usually results in chaos. In reality, the best way to make a system work is to have that system in place before you hire your first staff. There will then be no arguments about implementation. A major risk for companies, especially in today’s economy, is losing key staff. Capturing knowledge and understanding through digital workflows can mitigate this by building, what a former consultant of mine, referred to as a 'corporate brain'. This acts as the "how to" guides for any new staff, a reminder to existing staff and a springboard for developing new ideas and improvements if properly designed. Despite what many people think and fear, a good project management system should never inhibit creativity, it should facilitate it. (And don't forget to back up your computers!) 10. Have an exit plan “All the world is a stage and the people merely players”. Good old Shakespeare. A line for every occasion. But like any actor, for a business leader, there is a best time to exit stage left. Hanging on to your position by the fingernails is singularly unattractive. The question of exit comes back to why you do the job and what you want to achieve. If it is simple monies and perceived prestige, then moving companies frequently is likely the best strategy – before you are found out. If you care deeply about your business, staff, and clients, then it becomes much trickier and this is where you need to consider ensuring continuity and who you want to pass the baton to. In knowledge-based companies, a common dilemma is that as you become more successful you move further and further away from the science and higher up the management ladder. This may not be what you want, nor what your clients want. The dilemma is that if you hand over to a new management team in order to focus on the science, you may find they have a different strategy and yourself out of a job. Been there, done that! Be prepared to make a choice. Once you exit, walk away and don’t look back! A pdf version of this blog is available here. PDF

Dinner with the romantic poets in the early years of the 19th century must have been a bundle of laughs, as they wrestled with the transience of life and the realities of the industrial revolution. The world around them was rapidly changing in ways that few could comprehend, and that change was accelerating. The assurances and certainties of the past were gone as urbanization, technological advances and scientific questioning took hold. Faced with so much change the Romantics did what they could, which was a mix of getting very depressed, and writing about it, reminiscing about a past ‘golden age’, and writing about it, doing a runner to southern Europe, and writing about it, and seeking solace in various medicinal pick-me-ups (ok, drugs) to help them, well, write about it... As a consequence, and if nothing else, we do have a substantial literature on the impact of change in the early 19th century. A fear of change is true for every generation. You only need to look at today’s newspapers, blogs, and social media to realize that it is as prevalent today as any age in the past. Each generation always seems to reminisce about some past ‘golden age’. The problem is that those ‘golden ages’ are never the same. If only people compared notes. Invariably, the ‘golden age’ is a period in their lives or past that they themselves barely remember or which they did not fully understand at the time. As has been said by many others, those who always look back to a ‘golden age’ have truly awful memories. The Romantics were no exception, as they tended to forget the realities of cabbage for dinner, unsanitary housing, and death by age 40, if you were lucky (the average age for the 16-18th centuries in England). The reality is that for the majority, today’s industrialized, globalized, technological world is a better place to live, for all its faults. We live longer, eat better, have access to so much more data and knowledge at the click of a button. We can immediately call anywhere in the world on a mobile phone, which can also access the world’s libraries, tell us where we are at any time, direct us to the nearest café latte, hospital or meeting. I for one have no wish to return to the 1970s, the 1950’s and certainly not the 18th or 19th centuries. For me, the golden age is what we aspire to build not a past age. This is not to say that the present-day is not scary and that we should not be concerned about change. The Industrial Revolution certainly scared the Romantics and raised in them some very important philosophical and moral questions that are just as valid today. Not least amongst these was the question of technological advance and scientific inquiry driven “because we can” rather than “whether we should”. This was embodied in Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein”. This book was purportedly the product of a competition to write the best horror story, between Mary, her husband Percy Shelley, Lord Byron and John Polidori whilst they spent the summer of 1816 on the shores of Lake Geneva, on their way south. But it is a far deeper piece of literature than just a piece of “horror” fiction and something that all scientists should read. When I was at Chicago, “Frankenstein” was still essential reading on their ground-breaking Western Civilization course, which I assume it still is. There was also the question of permanence and through this, the question of what do each of us leave behind and does it matter? In short, how will we be remembered? In his poem “Ozymandias”, from which the quote that leads this blog is taken, Shelley describes all that there is left to show of a once powerful king, as a metaphor for us all. “Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!” Now, just ruins. And yet… I was minded recently to think about this question by two conferences I attended 20 years part. The first conference, back in 1998, was a GIS conference in Florence, Italy. The second, a meeting of paleoclimate specialists in Colorado in 2016. Florence, 1998 It is hard not to attend a conference in Florence, especially one on maps. The atmosphere is heavy with the Renaissance, the libraries replete with ancient tomes and maps that are as much a work of beauty as of cartographic science. So ESRI Europe’s user group meeting in Florence could hardly fail, and it did not. The mix of academics, civil servants, decision makers, and industry specialists was stimulating. Through numerous conversations around posters and after talks I, for one, found solutions to some of the problems I was facing in petroleum exploration analytics, simply by seeing how other fields solved their problems. But, one conversation, over canapés and prosecco, made me stop and think. It was with a senior European civil servant, whose name I cannot remember if I ever knew it, who was close to retirement and who made the following statement to me, “that in our careers we can only ever hope to achieve one major thing”. I was relatively early in my own career and it left an impression. Could it be true? His argument was not in terms of numbers of projects or papers completed, but that at the end of the day you will be remembered for one thing and one big thing only. It is something that has stuck with me and something, to be honest, that at the time I did not believe at all Roll on 20 years…. Boulder, 2016 I had been out of Academia for over 20 years when I was invited to attend a paleoclimate workshop in Boulder, Colorado in early 2016. An impressive list of attendees and great discussions followed over two days, which I found scientifically therapeutic and a serious wake-up call to tell me that I had been in management too long. I also realized that I was getting old as I looked around and realized, to my chagrin, that the attendees who I thought were Ph.D. students were actually young professors - what they say about policemen looking younger and making you feel old, the same is true for professors! But when one person told me how they had read my work and used it for years, I was gratified, reassured, flattered. But the lingering question was this: was that my one achievement in my career that I would be remembered for? And that work was already 20 years old 2017. All change A year later, and I found myself self-employed. As an executive director for 10 years, my focus had been on management, strategy, and marketing. But, now here was an opportunity to regain my academic ‘mojo’, to catch up on research, teaching and several decades of scientific papers. An almost impossible task. Thank goodness for Kimbo espresso coffee, good wine and a range of great cookbooks… Now, after 24 months I have a major paper published, with several more on the way. New datasets in progress, a completely new data management system and suite of workflows, and an array of new ideas to promote. And most importantly, I have a reinvigorated curiosity about the Earth - my scientific ‘mojo’ is back. In so doing I also found an answer to my question. Are we limited to achieving only one big thing? No. Of course not. We can always do more. It is about time and priorities. And therein lies the issue. Once we get into our careers, where ever that takes us, time goes quickly. No sooner have we started then we are looking back. For me, it was when I was around 35. Next thing I knew I was close on 55. There is also the problem that at the very point that we can contribute most to science given our experience, that experience takes us into management where we can no longer do the science. Something is wrong with that surely! So, are there any lessons to learn that might help you if you are in the same position? Let me suggest a few thoughts:

Postscript As for Shelley and his companions watching the sunset over Lake Geneva? It is sobering to think that within eight years of their writing competition in Switzerland, Percy Shelley, John Polidori, and Lord Byron would all be dead, and all at a young age, 29 (1822), 25 (1821) and 35 (1824), respectively. Nothing is forever A pdf version of this blog is available here. PDF

|

AuthorDr Paul Markwick Archives

November 2023

Categories |

|

Copyright © 2017-2024 Knowing Earth Limited

|

E-mail: contact@knowing.earth

|