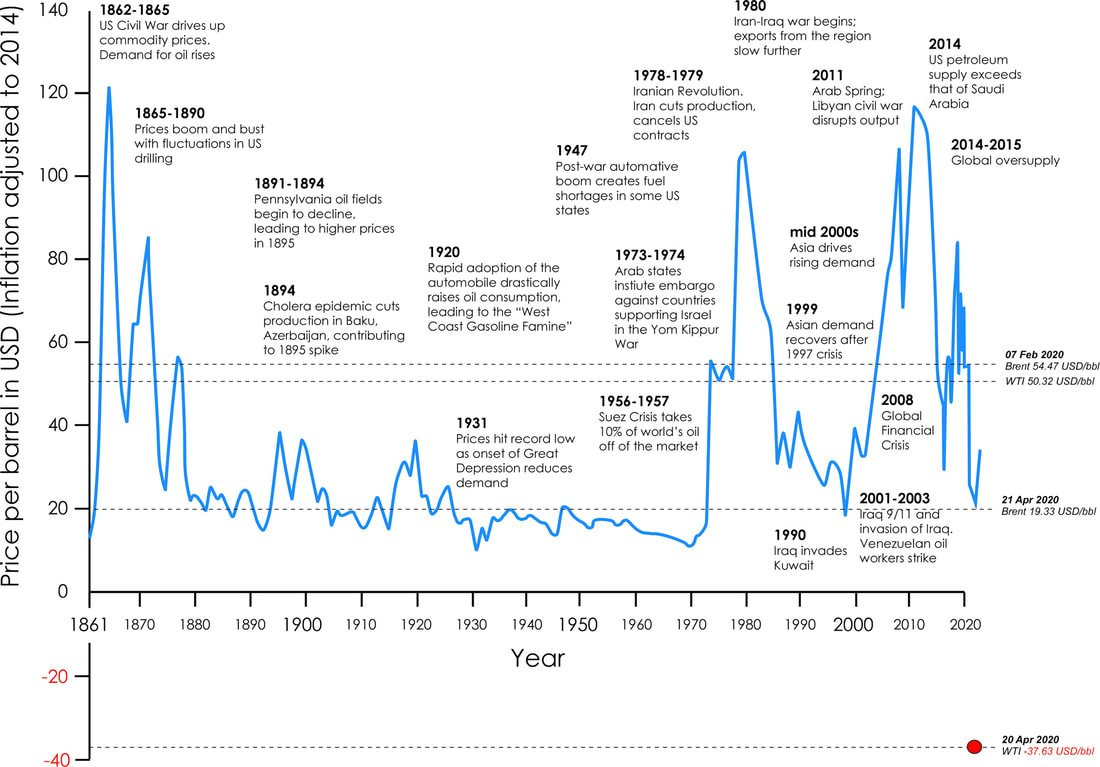

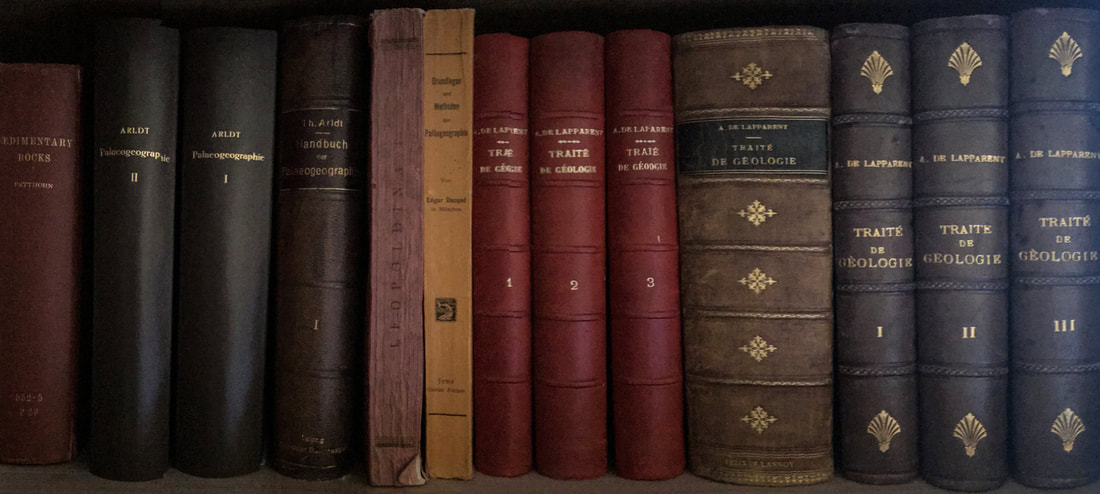

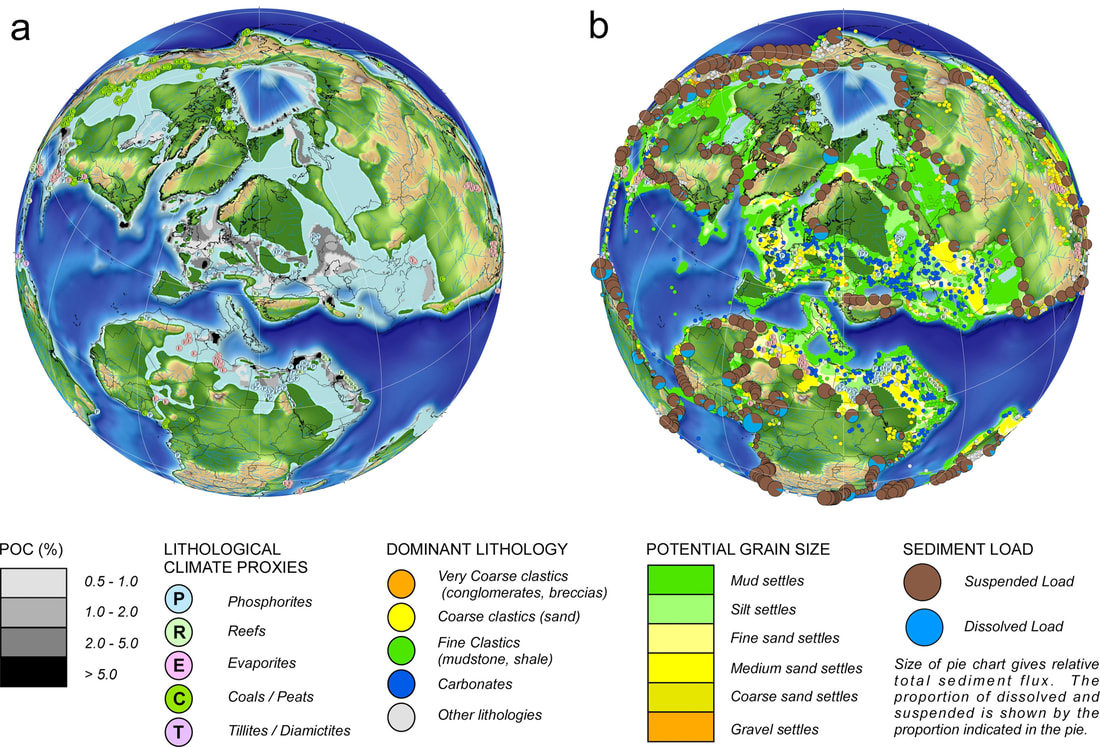

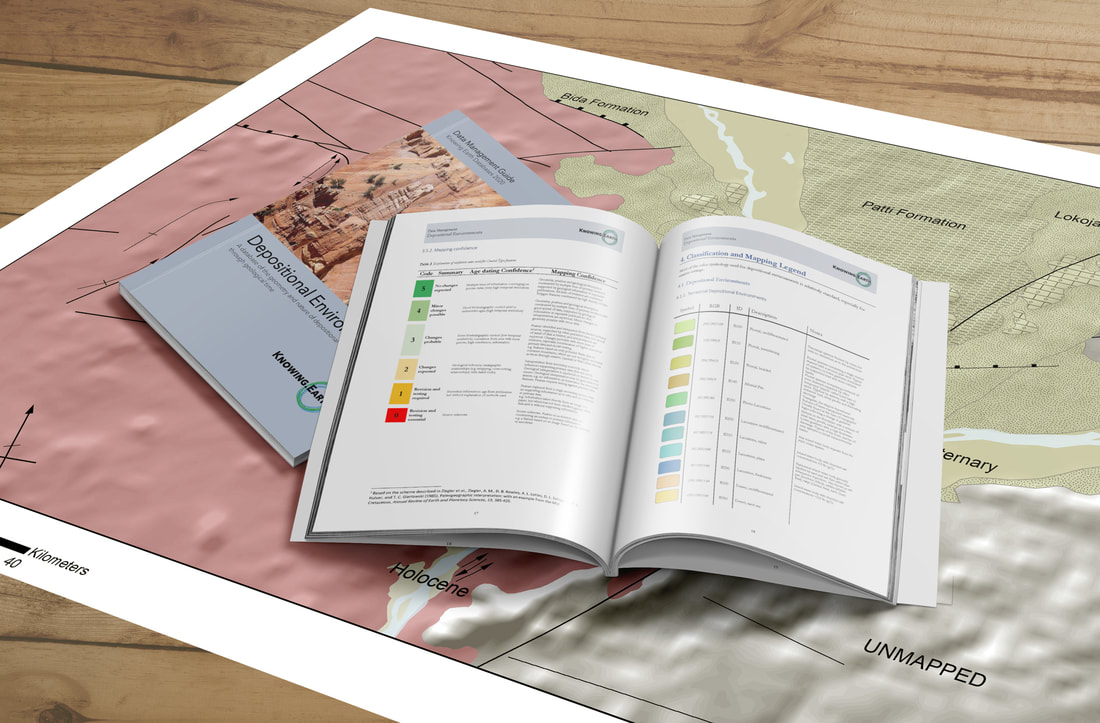

“Alexanders is closed” What next for exploration? I thought I was being very organized last winter as I built up a portfolio of blogs and articles to provide myself with materials to post during 2020. What a great idea! Planned commercial projects were coming in and I knew that these would take up much of my time. Even as news of the epidemic filtered out of China in January, there was a sense that this was to be a repeat of SARS. But as I got ready to post today’s article at the end of February, the news from northern Italy showed all too clearly that this coronavirus had spread beyond China and that this was not going to follow the geographic limits of its predecessor SARS. It is ironic, that this blog is about a changing exploration industry. And now five months later, everything has changed. But in re-reading what I wrote I believe it is still a relevant discussion. So... Houston: Cowboys, oil, alligators, and steak… A world that has gone? Should go? Or is it just on hold? Your answer will depend on your politics and vision of the future. Whatever your view, the world is certainly changing, and that change needs to be managed. So, what next? Or do we just wait and see what happens? That might work for some… in the swamp… The sign on the door was clear, “Alexanders is closed”. It was April 2017 and after 10 hours on an economy flight from London, it was not what I wanted to see. But the reality was there for all to read. Alexander's restaurant (http://jalexanders.com) at the corner of Westheimer and Wilcrest had long been my refuge. It had been there for as long as I had been visiting Houston. First as Houstons then as Alexanders. A place to relax and think, to meet with friends, enjoy a steak after a long flight or a days’ meetings. My usual dilemma was whether to go for their ‘famous’ baby back ribs or the filet mignon with a béarnaise sauce. Then there was their “vegetable of the day” of which the sautéed spinach, creamed spinach, grilled zucchini, and beefsteak tomatoes are, or rather were, worthy of note. The baked potato fully loaded was usually a step too far as I saved myself for their wonderful carrot cake. So moist. So bad... And now it was gone… Whilst for many of you the closure of Alexanders is completely inconsequential, especially now, and indeed most of you have probably never heard of Alexanders, for me, it was yet more evidence of changing times and the loss of reassuring certainties. Little did I know… This graph is based on that shown on the World Economic Forum website in 2016 https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/12/155-years-of-oil-prices-in-one-chart/) modified to include more recent changes (from Bloomberg). The original version of the graph is cited as Goldman Sachs (see additional references on the weforum page). The fluctuations in prices are clear, especially over the last 40 years There are cycles and there are cycles... The oil and gas industry has always been cyclic and many of us have seen many - far too many - downturns and recoveries. Indeed, many old-timers seem to keep track of their careers by the number of downturns they have seen and survived. Each recovery in the past has seen an increase in budgets and a major hiring drive, as business returned to 'normal'. But the last downturn has been different, starting in 2014, and now exacerbated by the consequences of COVID-19. Yes, we as an industry are faced by many challenges, not least the transition from fossil fuels to a more diversified energy portfolio, the vagaries of unconventionals or the political game playing between the worlds leading oil producing countries. Each deserves a blog in its own right. But the change that concerns me the most, and which I think will have the biggest ramifications not only for our industry but for Earth education in general, is the loss of experience. The Alamo, San Antonio. A metaphor for our industry? No. Changing demographics: the good, the bad, and the seriously worrying… As I walked around last year’s AAPG convention in San Antonio I was struck by the greater number of young geologists and the broader diversity of attendees than in previous years. This was great to see. Change is happening and it is no bad thing. But with all the new faces there was also the demonstrable absence of old faces and with that experience and expertise. it is true that each past downturn has resulted in a gap or pause in the staff demographics as potential graduates looked at what was happening and opted for different careers. The resulting demographic imbalance has been long recognized, and many, if not most companies were actively addressing this through mentoring, knowledge transfer, and digital knowledge and database systems. But the depth and extent of this last downturn have left this process of knowledge transfer incomplete. More significantly, it has seen a generation of experience opt for early retirement and a younger generation who are increasingly deciding against the Earth sciences. This has been compounded by a general reticence to hire significantly this time given uncertainty over the future. The question is, have we lost so much of our experience in this last downturn that this will affect our recovery as an industry and especially our ability to brainstorm and solve the challenges that now face us? An industry of the brightest scientists and engineers… Our industry can boast some of the brightest scientists and engineers of the 20th and 21st centuries. We have been at the forefront of increasing the understanding of our planet from tectonics, to depositional processes to paleontology and beyond. Our industry has developed and build technologies and tools that can send sound waves into the Earth to resolve the structure of the subsurface even down to the Moho (the base of the crust) and can now drill through kilometers of rock from rigs sited in two kilometers of water and still know where the drill head is within meters. That is quite incredible. Well, I am still impressed This is something that we should be extremely proud of. Achievements that we should shout about far more than we do. The new generation is equally gifted, if not more so. I have been lucky to hire and work with many excellent young geologists. But they would be even better with mentoring from and access to experienced staff. But those experienced staff have either left or are about to leave the Industry. (As I was about to post this article, I received an e-mail from a friend in Houston who had just announced that she was leaving the Industry. Carmen is one of the most impressive scientists I have worked with and a great role model for the next generation and especially the growing number of young women joining the industry. Her departure is a devastating loss and one the Industry can ill-afford). Experience is key! This is all the more important as we apply our industry’s skill-base to energy transition and building new business models. Experience is about having seen numerous real-world examples and being able to draw on these when making decisions, warts, and all. Knowing what worked, what failed, and why. As my Ph.D. advisor repeatedly told me "the best geologists are those who have seen the most rocks". (I am convinced that this is something said by every Ph.D. advisor to every geology Ph.D. student, but that makes it no less true). And that places us in something of a cleft stick. On the one hand, the Industry is addressing past diversity issues and hiring a new generation of enthusiastic, talented, Earth scientists, albeit in limited numbers. Whilst simultaneously cutting costs. Great… But, on the other hand, we have lost the experience and expertise we need to both mentor the next generation and also to make informed decisions as we start to explore once more. So, what to do? Let me respectfully offer a few suggestions: 1. Make more from what you have Today companies have libraries filled with 3rd party reports, internal studies, presentations, and databases. That is an incredibly powerful resource, but only if used. The challenge is to understand what you have and how to integrate this within your current workflows. What data and knowledge are good? What is bad? What can you accept and what should you ignore? It is certainly advantageous to know where the skeletons are before you repeat past mistakes! Mistakes cost time and monies. Why spend more monies if you already have the answers, or resources to get to the answers, in-house? An easy win is to get your libraries curated and databased. In some companies, this has already been done. It is something I spent 2019 doing with my libraries (see my blog on scanning) Another solution is to bring in the original product builders and get them to explain what they did and where useful, updating their products to fit new corporate workflows. This is certainly where much of my time would have been focussed this year (until some errant RNA intervened), having spent the last 25 years designing, building, and selling products and solutions to exploration companies. One problem with seeking out the builders is that whilst their companies may still exist (possibly) the authors themselves may have moved on. The same is true when looking for your own staff who made the original purchases with a specific plan in mind and/or who used the products. You may need to visit the golf courses of Houston or drive out to the Hill Country (though obviously not Alexanders) – ‘social distancing’ notwithstanding. Many of you may have access to the excellent global resources that are now available. I was privileged to be instrumental in the development of several of these, working and building some great teams. The challenge, as an exploration group, is how to get more from these. They each have their own strengths, and each was designed for slightly different purposes. What do you need to know to unleash their potential? Feel free to drop me a line. This image is based on my 2019 paper and 30 years of research and experience 2. Strengthen relationships with University research groups University research groups have always been a great source of cutting-edge ideas, knowledge, understanding, and data. Not to mention future staff. With down-sizing and the disappearance of company-based research groups, universities are becoming all the more important. This is not just about bringing in a professor to give a one-off seminar, but from my experience is best achieved through more active participation through workshops, having academics work directly with teams, and through MSc and Ph.D. projects and internships. As an example, last year I participated in a week-long workshop for a company that convened leading academics from different research groups and with varying opinions. In a few days, staff were exposed to all the views and background from the leaders in the field, something that would have taken them months to get a handle on by only reading their papers, and which even then, would not have provided the insights into the mindsets of the protagonists. (There is also a need to maintain a presence in Academia at a time when our industry is increasingly perceived negatively). 3. Go back to the basics. Get out the pencil crayons. Get your young staff to look at paper copies of seismic and use colored pencils to identify horizons. The key is to encourage your teams to understand the data, know their data, and to ask questions. They should not be afraid to disagree with their elders, but wise enough to know that experience can be an advantage. We are not infallible, but we have seen more rocks and solved more problems. 4. Understand the whole system, what to ask, who to ask and where to find solutions. With fewer staff and the disappearance of the armies of specialists we used to have, it is key that the next generation knows how the Earth system fits together. This does not mean going all "fruit salad" (my thanks again to Catherine for that wonderful imagery), in which our staff have a little bit of knowledge of everything but no real depth. This is about ensuring that our teams know the vocabulary and key headlines of diverse scientific fields and most importantly that they know enough to be able to ask the right questions and know whom to ask or where to search for the answers. A picture I have used many times, but no less relevant for its repetition. When we consider any problem to do with the Earth system, whether in exploration or environmental change, we have so many components to think about. There is simply so much to take in! Where do we start 5. Do not assume that technology will solve everything… Over the last three years, advances in machine learning and AI have been impressive. Pattern recognition has indeed been around for many decades: auto-trace in seismic interpretation, or computerized fossil recognition in biostratigraphy. The limitation in the past was largely computer processing power, which is no longer such an issue. With data storage now relatively cheap, and especially the development of cloud storage, accessing data and knowledge from anywhere in the world should be child’s play. The problem is that whilst a child can operate an iPad with ease from kindergarten on, if not before, and they are incredibly computer savvy, they do not necessarily know the questions to ask. That comes with experience and does not seem to be always taught. As evidence ask them to do a Google search and see what they find; I am always amazed at what people do not find. Technology is wonderful, and I am a self-confessed addict having designed, built, managed and analysed computer-based databases for over 30 years. But don't forget the basics - ask questions, know your data, question everything. Operationally what should we do? Well that is your call, but let me suggest the following:

I have spent much of my career designing, building, and managing large, global databases. Key to their success is knowing where the data has come from, what can be used, and what should be thrown the trash or used with caution. There is a fundamental difference between data and verified data. One is a collection of words and numbers, the other is power. So, where next? The future is about preparing our new generations of Earth scientists with all that we have learned over the last century or more, what worked, what failed, and why. To know the questions to ask and where and how to find the answers. The next generation of Earth scientists needs to be well-grounded in the fundamentals of geology and the scientific method. At the same time, they need to be conversant with a broad range of scientific fields, or at least enough to know the vocabulary of diverse fields and how each discipline might impact the problem they are trying to solve. This also gives them transferrable skills that will aid the energy industry as we transition to alternative sources of energy, but also enable them to look at applying their expertise and experience to a range of other challenges, from the management of water resources to carbon capture, and storage (CCS), to geothermal energy, mineral exploration and waste management. They need to be familiar with the tools available, but not to assume they these will solve all the problems they find. At the end of the day, we need to harness all that we have learned in our industry to accelerate the next generation in understanding even more than we do for the betterment of mankind. Understanding the Earth is what we do! Epilogue. What happened to Alexanders? A search on the internet revealed that Alexanders Westchase closed at the end of January 2017 on the very same day that I had left my role as Technical Director of an Aim-listed consultancy after 12 years of successfully building the business. Coincidence I am sure…Rule #39 notwithstanding.. Today, what was once Alexanders in Westchase, Houston, is the site of a 24-hour emergency center. Useful and admirable, especially right now. Though I won't be going there for steak "Alexanders is closed". All change. Useful and admirable, but not quite the dining experience I was expecting. Image from Google Streetview. What would we do without Google? A pdf version of this blog is available here for download

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorDr Paul Markwick Archives

November 2023

Categories |

|

Copyright © 2017-2024 Knowing Earth Limited

|

E-mail: [email protected]

|