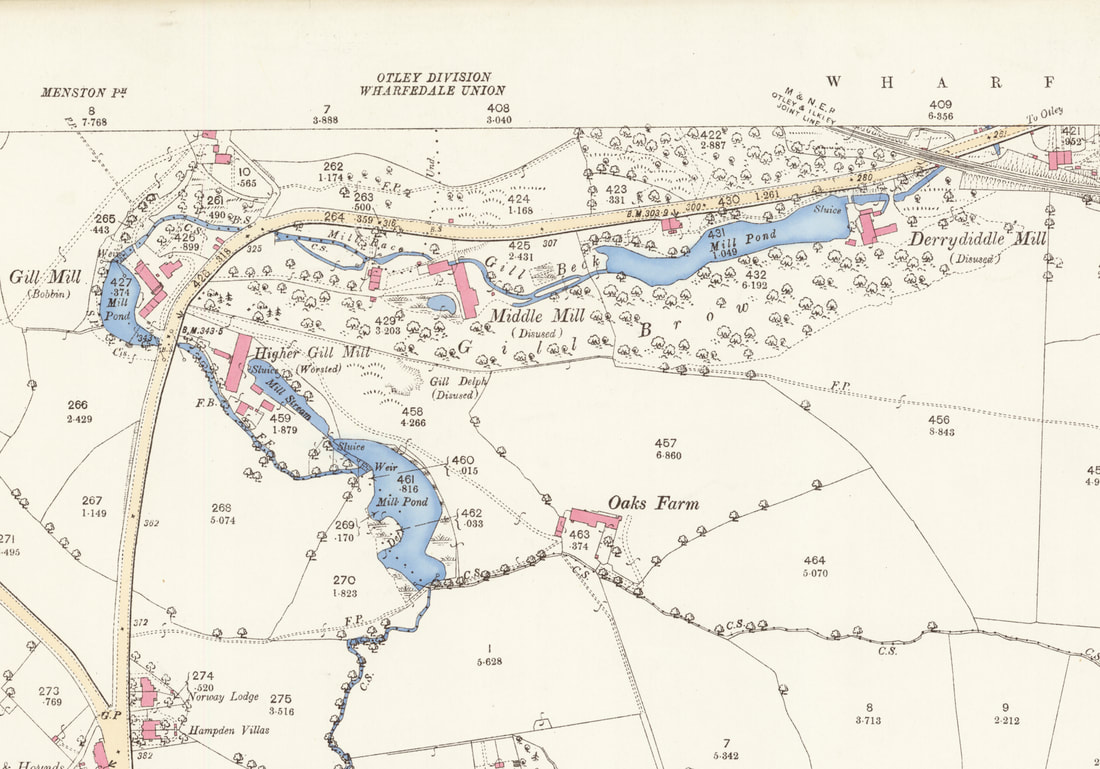

Welcome to the Energy Transition. Again!Sitting amongst the ruins of Derrydiddle Mill here in West Yorkshire, surrounded in the spring by wild garlic and bluebells, it is hard to imagine the hive of activity this would have been 200 years ago. The clatter of the carding and spinning machines, the water wheels turning, the carts coming back and forth over the narrow bridge to the Bradford Road. Today, we talk about 'the' energy transition as if this is the first time. But our relationship with energy has changed before. Here at Derrydiddle Mill, we have part of the record of one of those earlier energy transitions. In this case, from the power of running water to that of steam. This was a transition from mediaeval technology to that of the Industrial Revolution. What lessons can this history give us about how transitions happen and what to expect as we pursue our own 21st-century energy transition? Derrydiddle Mill: from Water to Steam. A 19th-century Energy Transition When, in 1815, Joshua Dawson and William Ackroyd travelled the short distance across the Chevin Hill from Guiseley to the Wharfe Valley, they established their first worsted wool mill here on Gill Beck (Ellar Ghyll), as it cuts down through a narrow gorge in the Millstone Grit on its way to join the River Wharfe at Otley. This site was a logical location with flowing water to drive the water wheels that would power the mills. But within a few years of establishing Derrydiddle Mill, Dawson and Ackroyd had moved the main centre of their operations to a location on the banks of the River Wharfe in Otley at what is now called Otley Mills. When I first read of this sudden move, I assumed this would provide an example of the energy transition from water to steam and proof of how quickly such changes can happen. But the story is a little more complex because this new site was also powered by water. Indeed, it was not until the 1840s that Ackroyd installed a steam-driven beam engine at Otley Mills. Only then, from the mid-1840s to 1850s, do we see the rapid adoption of steam power across the north of England and the development of the large mills that still dominate many cities and towns today. So, why the sudden move to Otley? Why did the transition to steam not happen immediately? Is this really a guide to how energy transition works? Can history tell us anything? Energy Transition can happen quickly, but not always when and why you might expect!

Derrydiddle Mill was the lowest of a series of mills distributed for a kilometre or so (0.6 miles) upstream of Derrydiddle; each assigned a different part of the worsted wool workflow. The power of moving water had been fundamental to industry, especially the wool industry in England, since the early Mediaeval period, some 600 years before Derrydiddle Mill was founded. Much of that early development had been by monastic orders, such as the Cistercians of Fountains Abbey, some 20 miles (c.32 km) to the north of us here, who had developed a business model and processes for wool production that might be considered a mediaeval mini-industrial Revolution. It was, therefore, not a surprise that Dawson and Ackroyd would start with this proven technology. But after moving to Otley Mills, Ackroyd and Dawson continued to use flowing water as their power source. This despite the fact that steam power had been around for 100 years before Dawson and Ackroyd moved their business to Otley. It was not until the 1840s that Ackroyd built his first steam-driven engine house (Richardson and Dennison 2020). So why move from Derrydiddle Mill? And why not which to steam straight away? Well, in part because this was a mixture of cost and technology. The Boulton and Watt designs, which Watt had patented, dominated steam beam engines throughout the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It was not until William McNaught's compound beam engine in 1845, and especially the development of the Corliss engine in 1849 with its rotary valves, that the market really changed. But also, there was no competitive need in those early days because most other mills were still running on water [sic]. The move from Derrydiddle Mill to Otley Mills appears to have been driven by two immediate considerations unrelated to energy transition: (1) Gill Beck did not provide the space for expansion, and (2) opportunity, the site was available, and a water management system was already in place. The space for expansion would become important in the following decades, not least because it allowed Ackroyd to bring all the worsted processes together into one integrated mill complex. The Otley Mills site had been the location of an old cotton mill dating back to the middle of the 18th century when the course of the river Wharfe had been modified to provide power. So here was a ready-made site that could, and was, adapted to worsted wool. But the world was changing, not just in terms of improving steam engine technology but also in terms of the business environment. It would be the combination of both of these developments that would ultimately drive the energy transition. 1815, the year Ackroyd and Duncan built their first mills on Gill Beck, was also the year of the Battle of Waterloo. The great upheavals that had stalked European politics since the French Revolution were starting to settle down, and with relative stability came an acceleration in Industrialization as international trade expanded. This period also saw the increasing availability of bank loans, the development of the canal transport network, which by 1840 was starting to be replaced by trains, expanding international trade routes, increasing urbanisation as workers abandoned rural life for the industrial towns and cities, and a growing middle class with an appetite for buying things, including more woollen suits. All these changes were soon to have an impact on that mediaeval technology of flowing water. When Ackroyd did switch to steam in the mid-1840s the effect on his business was immediate with a major expansion of the mill complex at Otley Mills. It also marked the growth of Ackroyd's fortunes as he became a significant player in local politics. But he was not alone. During the late 1840s-1850s, we see the consolidation of the numerous small mills in small towns into enormous single factories with their related communities. The largest of which was the famous Salts Mill (1853) at Saltaire (https://saltsmill.org.uk/), which at that time it was built was the largest industrial building, by floor area, in the world. Now, competition was driving businesses to transition to steam. In the middle of the 19th century, the bottom line was that if you didn't move to steam, you would lose out to those who had. So, the 19th century energy transition here in Otley was not just about technology or a desire to change. It was about the broader context of political, economic and societal changes, and then when the transition happened, the pressure of competition that was being driven by consumers. In our own time, we can think about the 'rapid' adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) over the last decade but how this varies by country. Tesla made owning EVs desirable. But they are expensive, so you need people with cash. You also need battery technology to the point where you can drive an EV as if it were a combustion engine. Finally, you also need a government willing to invest in infrastructure. So, the energy transition at the beginning of the 19th century was relatively rapid (decades) but not instantaneous. It was about technological advances, but also contemporary political, economic, and societal changes. It was also about the market – competition and demand. Transitions transition It is unclear how long Derrydiddle and its associated mills on Gill Beck remained active. The buildings and mill pond at Derrydiddle are labelled as "disused" on the 25-inch to 1-mile map of 1893. However, Gill Mill and Higher Gill Mill are not. This suggests that at least some of these mills remained operational until the end of the century. Intriguingly, 1893 is the first time it was named on a map as "Derrydiddle Mill". Part of the reason for this was probably to maximise Ackroyd's original investment in Gill Beck. But it was also because these older technologies still worked, just not as efficiently. So water-power and steam-power, mediaeval and industrial technologies, ran in tandem for at least 50 years in the Wharfe Valley. Adopting new technologies can be rapid, but this does not mean that older energy sources and technologies are instantly abandoned. Transition is about transition.

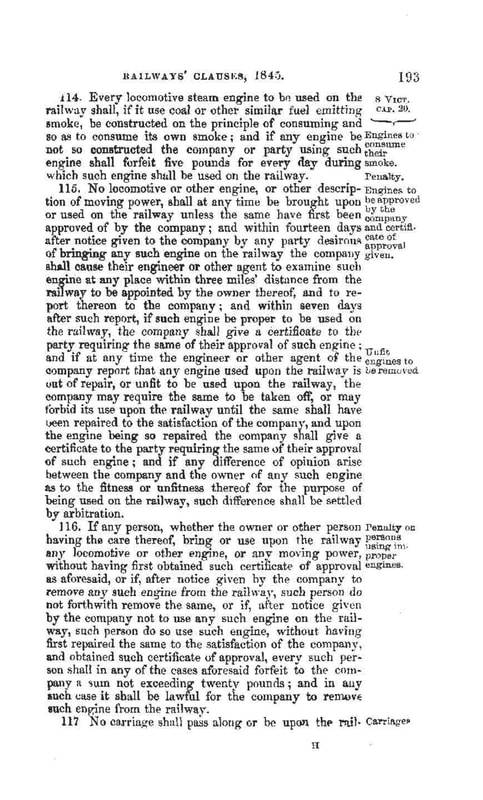

Change may not go in the direction you expect - the unfortunate case of unforeseen consequences The consequences of steam power were many and varied. Energy was no longer dependent on local sources, especially the power of flowing water, which had long kept businesses small and stuck in the hills. Although, it is no coincidence that much of the British Industrial Revolution was associated with the location of coal and iron fields. For the mill owners, steam provided a sudden increase in productivity, a move away from a dependence on manual labour, and a way to make bundles of cash! But perhaps the most significant change was the ability to move goods and people at speeds and 'ease' that had never been experienced in human history. For many, the steam train epitomises the Industrial Revolution and the modern age. The early experiments such as Stephenson's Rocket (1829) or the "Lion" built by Todd, Kitson, and Laird here in Leeds in 1837. These are just two of the many steam locomotives etched in our history that began a British love affair with steam trains. I must admit I like steam trains. Steam trains also had an unexpected societal benefit as the network expanded and people realised how much they liked or had to travel, the benefit being that in moving and mixing populations, the bane of inbreeding began to recede. But these early steam trains must also have been terrifying for a population that had grown up in the countryside, where nothing moved particularly fast. And not just the 'high' speeds and noise, but all that smoke. To address this concern, the Railway Clauses Consolidation Act of 1845 stipulated that all engines had to 'consume their own smoke' (HMG Railway Clauses Consolidation Act 1845):

Sadly, by 1845, industrialisation and societal changes were happening so quickly that this law was quickly abandoned or, at the very least, conveniently ignored. The reasons will be familiar to us: the train system was rapidly expanding, and coal had replaced coke as the primary energy source due to the sheer cost of producing coke and the increased demand for energy. In short, consumer demand trumped environmental sense and good intentions. For our current energy transition, it is clear that we will need more critical minerals such as cobalt and lithium. But as demand grows as we transition, what impact will that have on the countries that produce them and the politics of exploring for them? How much of our land are we willing to see turned over to solar farms? And what about nuclear? An excellent overview of the complexity of the problem can be viewed in Ed Conway's Sky News report on Chile and the consequences of the demand for critical minerals, https://news.sky.com/video/battle-for-chiles-critical-minerals-12643766). This is a salutary lesson from the Past. No matter how good your intentions are or how serious your (environmental) concerns are, the fear of individuals that they do not have enough money to buy food, heat their homes or care for their kids will trump everything else. This is exactly what we are seeing today (2023) in the UK, with a cost of living 'crisis', energy 'crisis' and climate' crisis'. So many crises, and no guesses for which of the crises people are now focussed on! Just as in 1845, this is not a statement of which of these crises is the most important for the long term, but the sobering reality of realpolitik. History is clear: change begets change, and sometimes, despite our best intentions, it may take us in directions that have negative consequences. There are always consequences. And those consequences can hit us very quickly. Driven by demand - the problem of increased consumption That problem of unforeseen consequences was largely driven by the growth in demand - the understandable desire to have a better life than your parents and to have all the new goodies that go with that way of life. Industrialisation initially improved the life of the average country worker, but as the population increased and more people moved to the cities, and more mill owners sought to make more monies, things got out of hand. When the population of Great Britain was 10.5 million at the turn of the 18th-19th century, switching to burning fossil fuels for energy was not such a problem. But during the 19th century, we see an increase in per capita energy consumption (1800: 37.750 kcal/day; 1900, 100,100 kcal.day; 2000, 135,800 kcal/day; Warde 2007), an increase in population (by 1900, the population of Great Britain was c.30.5m), and so a total increase in energy consumption. The fastest levels of consumption growth were between the mid-1830s and mid-1870s, so it is no surprise that this coincided with high pollution, degradation, poverty, and disease. The "great stink" of 1858 in London was just one expression of this trend. Although many of these problems were ultimately overcome, for much of the 19th century, a life that had started to look so much better suddenly became rather unpleasant. When considering energy transition, do not forget what drives our insatiable demand for energy. Renewables require battery technologies, and these are resource-limited. Consumption is the elephant in the room. And it is a very big elephant! A pre-industrial life does not necessarily mean a good life One final thought on Derrydiddle Mill. There is often a rose-tinted view of the world before Industrialisation. We can see this in the words of many environmental groups today. But such a view is far from new. The Romantic movement of the late 18th and early 19th century harked back to an idyllic lifestyle that never actually existed unless you were independently wealthy, as most of the romantic poets were (or they knew someone who was!). Life before the Industrial Revolution was not good. Life expectancy for the majority was short (less than 32.4 years for Londoners prior to the 1810s when Derrydiddle was built; Mooney 2002), and freedoms were limited. Working at Derrydiddle Mill, though based on water power, may not have been pleasant and was certainly not idyllic. But it was a paid job! We also need to remember that before the Industrial Revolution and the rapid adoption of fossil fuels as the primary power source, it was not as though only water or wind were used. Coal and peat have a long history of usage, going back to the Romans. Indeed, for much of human history, the dominant source of energy was burning wood. The Past is not necessarily an idyll. But we can learn from it and extract the best points. |

| The Hay Wain by John Constable (1821). The romantic view of a pre-industrial rural world. Image from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Constable_-_The_Hay_Wain_%281821%29.jpg |

Final thoughts: What clues can the past give us?

Today, we have the benefit of advanced technologies, science and an ability to quickly and easily look at history through digitised records, from which we can draw on lessons and learnings. If we so wish.

What can we learn from that early 19th-century energy transition?

What can we learn from that early 19th-century energy transition?

|

Of course, this is not a simple comparison.

Whilst the lessons from the 19th century may provide a guide to how change happens, there is a fundamental difference between then and now.

Today, the main driver for change is political and societal pressure for an energy transition to low or non-carbon sources in response to concerns over climate change. This driver was not something that the early 19th-century business community faced, William Wordsworth notwithstanding (the subject of a future blog).

We will have to leave it to future historians to record whether such pressures are enough to drive the energy transition or whether, in the end, it is money and the market that ultimately dictate how and when change happens.

The ruins of Derrydiddle Mill today make for a very pleasant afternoon walk. They remind us of a past energy transition that shaped the modern world. How that energy transition happened may provide clues about dealing with similar challenges today, or at least the pitfalls and drivers to watch out for.

But one thing is clear: there is no going back.

Whilst the lessons from the 19th century may provide a guide to how change happens, there is a fundamental difference between then and now.

Today, the main driver for change is political and societal pressure for an energy transition to low or non-carbon sources in response to concerns over climate change. This driver was not something that the early 19th-century business community faced, William Wordsworth notwithstanding (the subject of a future blog).

We will have to leave it to future historians to record whether such pressures are enough to drive the energy transition or whether, in the end, it is money and the market that ultimately dictate how and when change happens.

The ruins of Derrydiddle Mill today make for a very pleasant afternoon walk. They remind us of a past energy transition that shaped the modern world. How that energy transition happened may provide clues about dealing with similar challenges today, or at least the pitfalls and drivers to watch out for.

But one thing is clear: there is no going back.

About the Author

| Paul Markwick is CEO of Knowing Earth, a scientific consultancy based in northern England. He has spent a career investigating the Earth system and applying this understanding to natural resource exploration. Paul's expertise includes global and regional tectonics, palaeogeography, palaeoclimatology and palaeoecology, on which he has published extensively. Paul has a BA from Oxford and a PhD from The University of Chicago. Contact details: [email protected] |

The full version of this blog is available as a pdf here

0 Comments

Leave a Reply.

Author

Dr Paul Markwick

Archives

November 2023

April 2023

April 2022

April 2021

November 2020

July 2020

March 2019

February 2019

January 2019