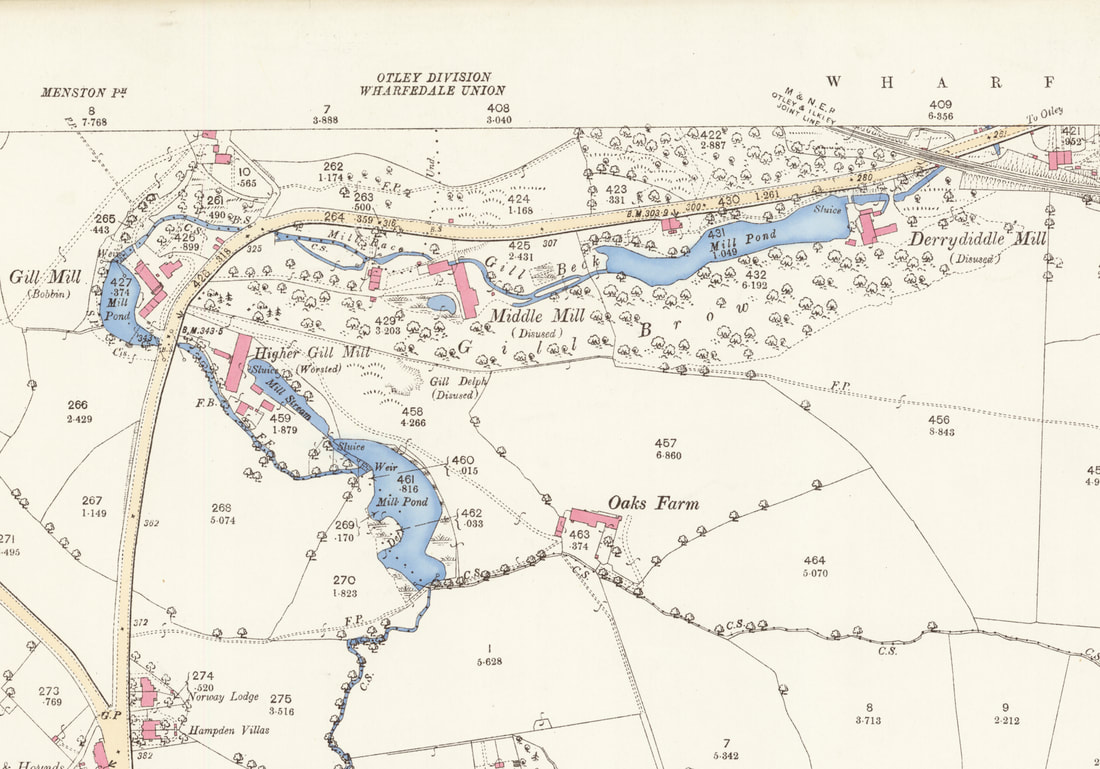

Welcome to the Energy Transition. Again!Sitting amongst the ruins of Derrydiddle Mill here in West Yorkshire, surrounded in the spring by wild garlic and bluebells, it is hard to imagine the hive of activity this would have been 200 years ago. The clatter of the carding and spinning machines, the water wheels turning, the carts coming back and forth over the narrow bridge to the Bradford Road. Today, we talk about 'the' energy transition as if this is the first time. But our relationship with energy has changed before. Here at Derrydiddle Mill, we have part of the record of one of those earlier energy transitions. In this case, from the power of running water to that of steam. This was a transition from mediaeval technology to that of the Industrial Revolution. What lessons can this history give us about how transitions happen and what to expect as we pursue our own 21st-century energy transition? Derrydiddle Mill: from Water to Steam. A 19th-century Energy Transition When, in 1815, Joshua Dawson and William Ackroyd travelled the short distance across the Chevin Hill from Guiseley to the Wharfe Valley, they established their first worsted wool mill here on Gill Beck (Ellar Ghyll), as it cuts down through a narrow gorge in the Millstone Grit on its way to join the River Wharfe at Otley. This site was a logical location with flowing water to drive the water wheels that would power the mills. But within a few years of establishing Derrydiddle Mill, Dawson and Ackroyd had moved the main centre of their operations to a location on the banks of the River Wharfe in Otley at what is now called Otley Mills. When I first read of this sudden move, I assumed this would provide an example of the energy transition from water to steam and proof of how quickly such changes can happen. But the story is a little more complex because this new site was also powered by water. Indeed, it was not until the 1840s that Ackroyd installed a steam-driven beam engine at Otley Mills. Only then, from the mid-1840s to 1850s, do we see the rapid adoption of steam power across the north of England and the development of the large mills that still dominate many cities and towns today. So, why the sudden move to Otley? Why did the transition to steam not happen immediately? Is this really a guide to how energy transition works? Can history tell us anything? Energy Transition can happen quickly, but not always when and why you might expect!

Derrydiddle Mill was the lowest of a series of mills distributed for a kilometre or so (0.6 miles) upstream of Derrydiddle; each assigned a different part of the worsted wool workflow. The power of moving water had been fundamental to industry, especially the wool industry in England, since the early Mediaeval period, some 600 years before Derrydiddle Mill was founded. Much of that early development had been by monastic orders, such as the Cistercians of Fountains Abbey, some 20 miles (c.32 km) to the north of us here, who had developed a business model and processes for wool production that might be considered a mediaeval mini-industrial Revolution. It was, therefore, not a surprise that Dawson and Ackroyd would start with this proven technology. But after moving to Otley Mills, Ackroyd and Dawson continued to use flowing water as their power source. This despite the fact that steam power had been around for 100 years before Dawson and Ackroyd moved their business to Otley. It was not until the 1840s that Ackroyd built his first steam-driven engine house (Richardson and Dennison 2020). So why move from Derrydiddle Mill? And why not which to steam straight away? Well, in part because this was a mixture of cost and technology. The Boulton and Watt designs, which Watt had patented, dominated steam beam engines throughout the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It was not until William McNaught's compound beam engine in 1845, and especially the development of the Corliss engine in 1849 with its rotary valves, that the market really changed. But also, there was no competitive need in those early days because most other mills were still running on water [sic]. The move from Derrydiddle Mill to Otley Mills appears to have been driven by two immediate considerations unrelated to energy transition: (1) Gill Beck did not provide the space for expansion, and (2) opportunity, the site was available, and a water management system was already in place. The space for expansion would become important in the following decades, not least because it allowed Ackroyd to bring all the worsted processes together into one integrated mill complex. The Otley Mills site had been the location of an old cotton mill dating back to the middle of the 18th century when the course of the river Wharfe had been modified to provide power. So here was a ready-made site that could, and was, adapted to worsted wool. But the world was changing, not just in terms of improving steam engine technology but also in terms of the business environment. It would be the combination of both of these developments that would ultimately drive the energy transition. 1815, the year Ackroyd and Duncan built their first mills on Gill Beck, was also the year of the Battle of Waterloo. The great upheavals that had stalked European politics since the French Revolution were starting to settle down, and with relative stability came an acceleration in Industrialization as international trade expanded. This period also saw the increasing availability of bank loans, the development of the canal transport network, which by 1840 was starting to be replaced by trains, expanding international trade routes, increasing urbanisation as workers abandoned rural life for the industrial towns and cities, and a growing middle class with an appetite for buying things, including more woollen suits. All these changes were soon to have an impact on that mediaeval technology of flowing water. When Ackroyd did switch to steam in the mid-1840s the effect on his business was immediate with a major expansion of the mill complex at Otley Mills. It also marked the growth of Ackroyd's fortunes as he became a significant player in local politics. But he was not alone. During the late 1840s-1850s, we see the consolidation of the numerous small mills in small towns into enormous single factories with their related communities. The largest of which was the famous Salts Mill (1853) at Saltaire (https://saltsmill.org.uk/), which at that time it was built was the largest industrial building, by floor area, in the world. Now, competition was driving businesses to transition to steam. In the middle of the 19th century, the bottom line was that if you didn't move to steam, you would lose out to those who had. So, the 19th century energy transition here in Otley was not just about technology or a desire to change. It was about the broader context of political, economic and societal changes, and then when the transition happened, the pressure of competition that was being driven by consumers. In our own time, we can think about the 'rapid' adoption of electric vehicles (EVs) over the last decade but how this varies by country. Tesla made owning EVs desirable. But they are expensive, so you need people with cash. You also need battery technology to the point where you can drive an EV as if it were a combustion engine. Finally, you also need a government willing to invest in infrastructure. So, the energy transition at the beginning of the 19th century was relatively rapid (decades) but not instantaneous. It was about technological advances, but also contemporary political, economic, and societal changes. It was also about the market – competition and demand. Transitions transition It is unclear how long Derrydiddle and its associated mills on Gill Beck remained active. The buildings and mill pond at Derrydiddle are labelled as "disused" on the 25-inch to 1-mile map of 1893. However, Gill Mill and Higher Gill Mill are not. This suggests that at least some of these mills remained operational until the end of the century. Intriguingly, 1893 is the first time it was named on a map as "Derrydiddle Mill". Part of the reason for this was probably to maximise Ackroyd's original investment in Gill Beck. But it was also because these older technologies still worked, just not as efficiently. So water-power and steam-power, mediaeval and industrial technologies, ran in tandem for at least 50 years in the Wharfe Valley. Adopting new technologies can be rapid, but this does not mean that older energy sources and technologies are instantly abandoned. Transition is about transition.

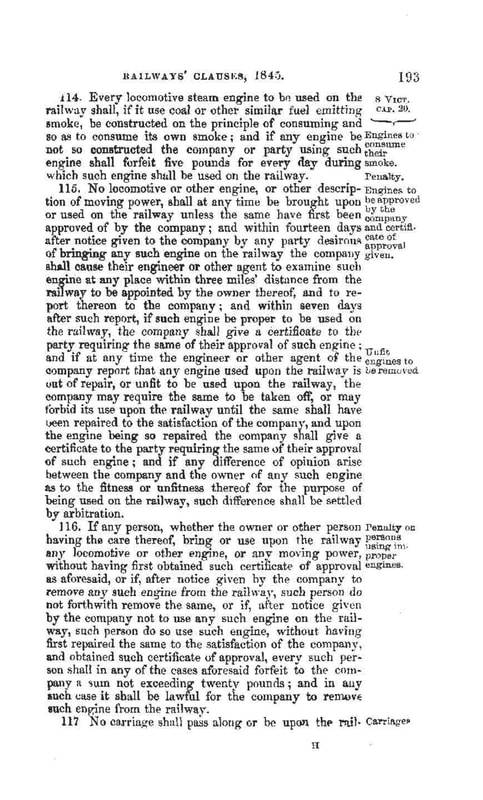

Change may not go in the direction you expect - the unfortunate case of unforeseen consequences The consequences of steam power were many and varied. Energy was no longer dependent on local sources, especially the power of flowing water, which had long kept businesses small and stuck in the hills. Although, it is no coincidence that much of the British Industrial Revolution was associated with the location of coal and iron fields. For the mill owners, steam provided a sudden increase in productivity, a move away from a dependence on manual labour, and a way to make bundles of cash! But perhaps the most significant change was the ability to move goods and people at speeds and 'ease' that had never been experienced in human history. For many, the steam train epitomises the Industrial Revolution and the modern age. The early experiments such as Stephenson's Rocket (1829) or the "Lion" built by Todd, Kitson, and Laird here in Leeds in 1837. These are just two of the many steam locomotives etched in our history that began a British love affair with steam trains. I must admit I like steam trains. Steam trains also had an unexpected societal benefit as the network expanded and people realised how much they liked or had to travel, the benefit being that in moving and mixing populations, the bane of inbreeding began to recede. But these early steam trains must also have been terrifying for a population that had grown up in the countryside, where nothing moved particularly fast. And not just the 'high' speeds and noise, but all that smoke. To address this concern, the Railway Clauses Consolidation Act of 1845 stipulated that all engines had to 'consume their own smoke' (HMG Railway Clauses Consolidation Act 1845):

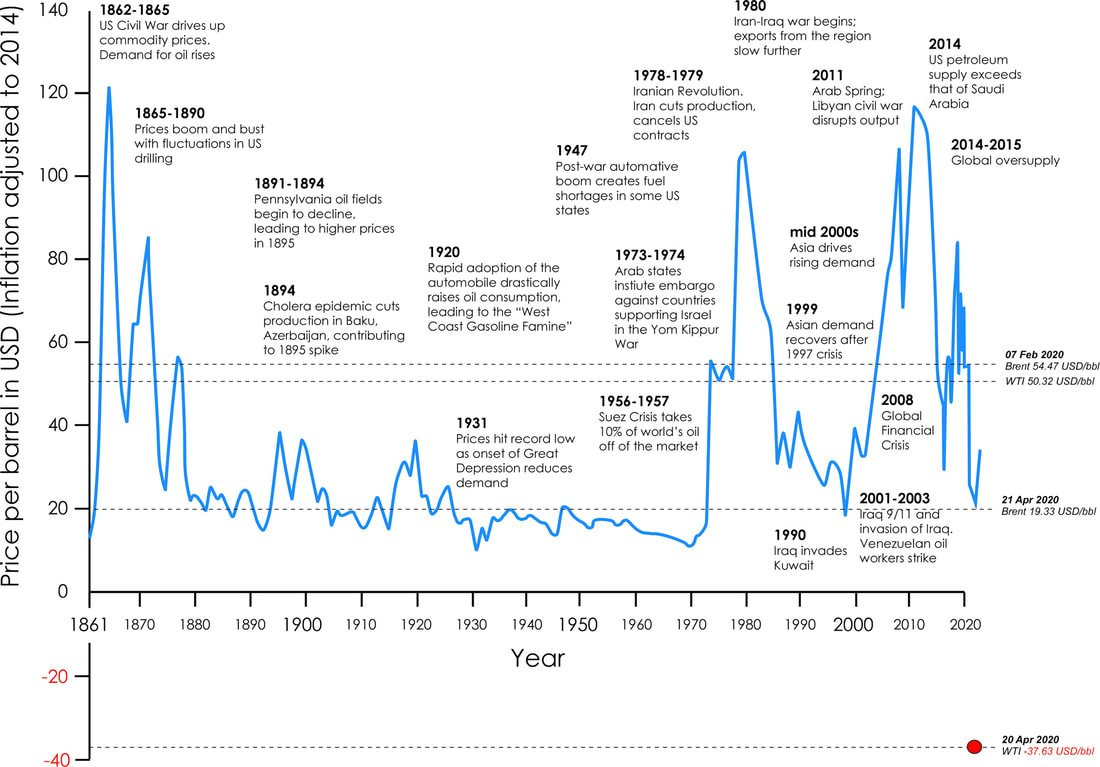

Sadly, by 1845, industrialisation and societal changes were happening so quickly that this law was quickly abandoned or, at the very least, conveniently ignored. The reasons will be familiar to us: the train system was rapidly expanding, and coal had replaced coke as the primary energy source due to the sheer cost of producing coke and the increased demand for energy. In short, consumer demand trumped environmental sense and good intentions. For our current energy transition, it is clear that we will need more critical minerals such as cobalt and lithium. But as demand grows as we transition, what impact will that have on the countries that produce them and the politics of exploring for them? How much of our land are we willing to see turned over to solar farms? And what about nuclear? An excellent overview of the complexity of the problem can be viewed in Ed Conway's Sky News report on Chile and the consequences of the demand for critical minerals, https://news.sky.com/video/battle-for-chiles-critical-minerals-12643766). This is a salutary lesson from the Past. No matter how good your intentions are or how serious your (environmental) concerns are, the fear of individuals that they do not have enough money to buy food, heat their homes or care for their kids will trump everything else. This is exactly what we are seeing today (2023) in the UK, with a cost of living 'crisis', energy 'crisis' and climate' crisis'. So many crises, and no guesses for which of the crises people are now focussed on! Just as in 1845, this is not a statement of which of these crises is the most important for the long term, but the sobering reality of realpolitik. History is clear: change begets change, and sometimes, despite our best intentions, it may take us in directions that have negative consequences. There are always consequences. And those consequences can hit us very quickly. Driven by demand - the problem of increased consumption That problem of unforeseen consequences was largely driven by the growth in demand - the understandable desire to have a better life than your parents and to have all the new goodies that go with that way of life. Industrialisation initially improved the life of the average country worker, but as the population increased and more people moved to the cities, and more mill owners sought to make more monies, things got out of hand. When the population of Great Britain was 10.5 million at the turn of the 18th-19th century, switching to burning fossil fuels for energy was not such a problem. But during the 19th century, we see an increase in per capita energy consumption (1800: 37.750 kcal/day; 1900, 100,100 kcal.day; 2000, 135,800 kcal/day; Warde 2007), an increase in population (by 1900, the population of Great Britain was c.30.5m), and so a total increase in energy consumption. The fastest levels of consumption growth were between the mid-1830s and mid-1870s, so it is no surprise that this coincided with high pollution, degradation, poverty, and disease. The "great stink" of 1858 in London was just one expression of this trend. Although many of these problems were ultimately overcome, for much of the 19th century, a life that had started to look so much better suddenly became rather unpleasant. When considering energy transition, do not forget what drives our insatiable demand for energy. Renewables require battery technologies, and these are resource-limited. Consumption is the elephant in the room. And it is a very big elephant! A pre-industrial life does not necessarily mean a good life One final thought on Derrydiddle Mill. There is often a rose-tinted view of the world before Industrialisation. We can see this in the words of many environmental groups today. But such a view is far from new. The Romantic movement of the late 18th and early 19th century harked back to an idyllic lifestyle that never actually existed unless you were independently wealthy, as most of the romantic poets were (or they knew someone who was!). Life before the Industrial Revolution was not good. Life expectancy for the majority was short (less than 32.4 years for Londoners prior to the 1810s when Derrydiddle was built; Mooney 2002), and freedoms were limited. Working at Derrydiddle Mill, though based on water power, may not have been pleasant and was certainly not idyllic. But it was a paid job! We also need to remember that before the Industrial Revolution and the rapid adoption of fossil fuels as the primary power source, it was not as though only water or wind were used. Coal and peat have a long history of usage, going back to the Romans. Indeed, for much of human history, the dominant source of energy was burning wood. The Past is not necessarily an idyll. But we can learn from it and extract the best points. |

| The Hay Wain by John Constable (1821). The romantic view of a pre-industrial rural world. Image from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:John_Constable_-_The_Hay_Wain_%281821%29.jpg |

Final thoughts: What clues can the past give us?

Today, we have the benefit of advanced technologies, science and an ability to quickly and easily look at history through digitised records, from which we can draw on lessons and learnings. If we so wish.

What can we learn from that early 19th-century energy transition?

What can we learn from that early 19th-century energy transition?

|

Of course, this is not a simple comparison.

Whilst the lessons from the 19th century may provide a guide to how change happens, there is a fundamental difference between then and now.

Today, the main driver for change is political and societal pressure for an energy transition to low or non-carbon sources in response to concerns over climate change. This driver was not something that the early 19th-century business community faced, William Wordsworth notwithstanding (the subject of a future blog).

We will have to leave it to future historians to record whether such pressures are enough to drive the energy transition or whether, in the end, it is money and the market that ultimately dictate how and when change happens.

The ruins of Derrydiddle Mill today make for a very pleasant afternoon walk. They remind us of a past energy transition that shaped the modern world. How that energy transition happened may provide clues about dealing with similar challenges today, or at least the pitfalls and drivers to watch out for.

But one thing is clear: there is no going back.

Whilst the lessons from the 19th century may provide a guide to how change happens, there is a fundamental difference between then and now.

Today, the main driver for change is political and societal pressure for an energy transition to low or non-carbon sources in response to concerns over climate change. This driver was not something that the early 19th-century business community faced, William Wordsworth notwithstanding (the subject of a future blog).

We will have to leave it to future historians to record whether such pressures are enough to drive the energy transition or whether, in the end, it is money and the market that ultimately dictate how and when change happens.

The ruins of Derrydiddle Mill today make for a very pleasant afternoon walk. They remind us of a past energy transition that shaped the modern world. How that energy transition happened may provide clues about dealing with similar challenges today, or at least the pitfalls and drivers to watch out for.

But one thing is clear: there is no going back.

About the Author

| Paul Markwick is CEO of Knowing Earth, a scientific consultancy based in northern England. He has spent a career investigating the Earth system and applying this understanding to natural resource exploration. Paul's expertise includes global and regional tectonics, palaeogeography, palaeoclimatology and palaeoecology, on which he has published extensively. Paul has a BA from Oxford and a PhD from The University of Chicago. Contact details: paul.markwick@knowing.earth |

The full version of this blog is available as a pdf here

0 Comments

A Guide to Taking Geological Field Photos. 2. What Kit do I Need?

Paul Markwick

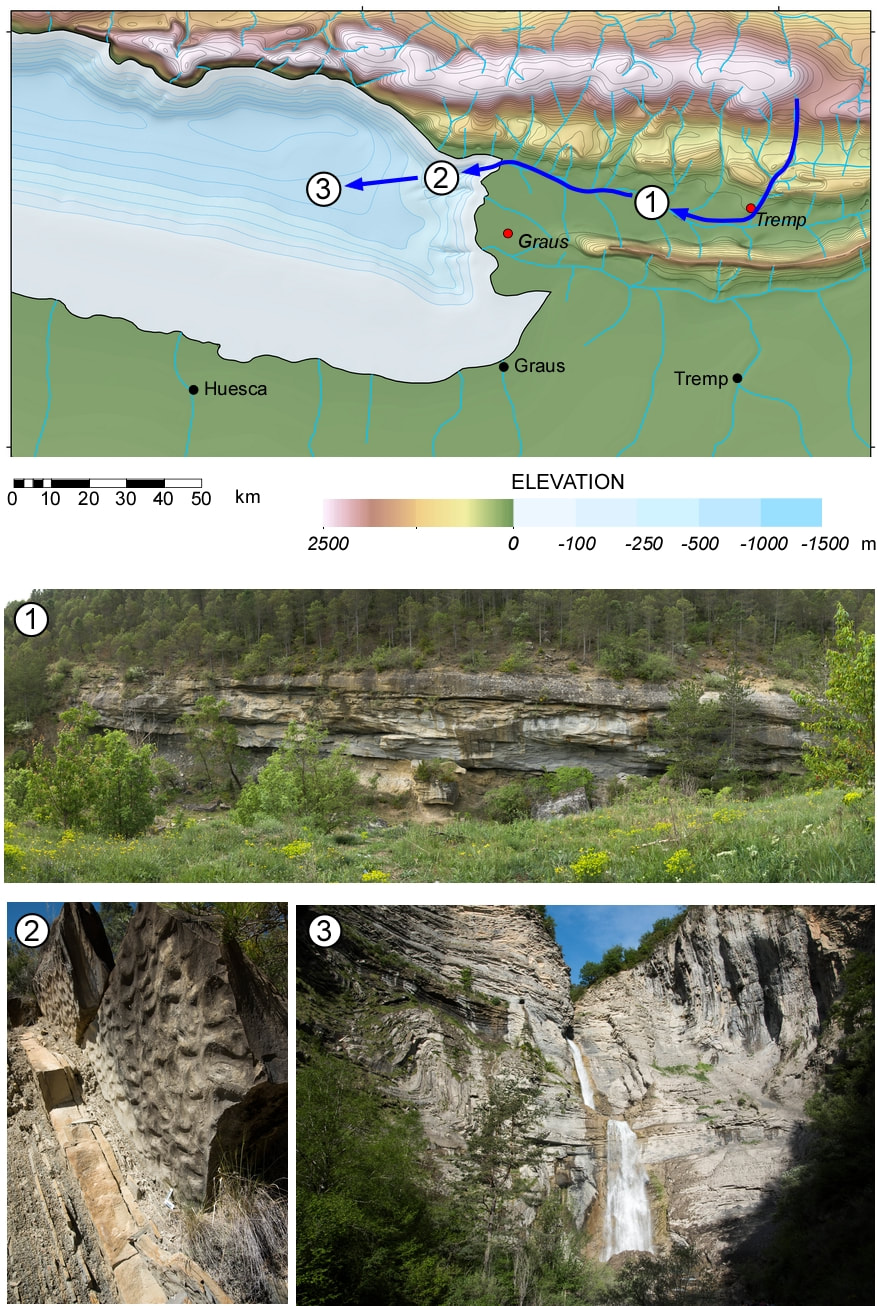

Fieldwork is an integral part of science and especially the Earth sciences. Indeed, for many of us, getting out into the 'field' is the main reason why we became geologists in the first place. Central to fieldwork is making and recording primary observations. For this photography is a key tool. Back in 2020, I wrote a blog with ten tips for field photography. This formed the basis for two online workshops during the UK's second lockdown in 2021. Two questions kept coming up, (1) what photographic field kit did I use? and (2) is a phone camera good enough for field photography? In this blog I provide some answers to both these questions by describing my fieldwork experience and some of the field photography equipment I use. Hopefully, you will find this of use.

Photographic equipment can be quite personal, and I am sure many of you will have your own preferences. It is also a question of budget.

Of course, for many of you for whom photography is a hobby and not just a tool, you will want to have equipment that enables you to take great photographs as well as recording what you see.

The best starting place for considering field gear is to ask a very simple question: "Why do we need a camera for fieldwork?"

The answer to that question takes us back to why we do fieldwork at all. The answer is to make and record primary observations in the real world. So the objective of fieldwork photography is to capture information so that you can communicate your observations.

Of course, for many of you for whom photography is a hobby and not just a tool, you will want to have equipment that enables you to take great photographs as well as recording what you see.

The best starting place for considering field gear is to ask a very simple question: "Why do we need a camera for fieldwork?"

The answer to that question takes us back to why we do fieldwork at all. The answer is to make and record primary observations in the real world. So the objective of fieldwork photography is to capture information so that you can communicate your observations.

1. Cameras or Smart Phones?

Digital technology has changed photography enormously over the last 20 years. For fieldwork, these changes have definitely been for the better. No longer are we limited by the number of pictures we can take (24 or 36 per roll multiplied by how many rolls of film we can afford or fit in our day bags), nor do we have to wait a week or more to see the results.

Which camera you use is as much about your budget and experience as anything else.

In choosing your camera, the best advice is to list the key features you need, such as sensor resolution, size, and price. Then, check this list against what is on offer. There is a considerable amount of help now available online. YouTube has a range, but I can recommend Ken Rockwell's excellent review site, https://kenrockwell.com/index.htm, or Digital Photography Review, https://www.dpreview.com/. I have used both in the past, especially Ken's website.

Once you have a shortlist, there is nothing better than going into a store, getting the 'feel' of the cameras on your list, and making a decision from this. You can then also get the advice of the experts in the store.

If the price is an issue, why not check second-hand deals from reputed camera stores?

My go-to DSLR is a Nikon D810 (https://www.dpreview.com/products/nikon/slrs/nikon_d810/specifications), which I have now had since about 2015. This is a great camera, but relatively large and heavy.

My decision here was based on several criteria:

(1) I needed a high-resolution sensor because I was using the photos for professional applications, and I already knew that I would need to zoom into a photo and crop it to get the images I wanted;

(2) a camera that was robust and weatherproofed (essential given where I take it);

(3) one that would give me the flexibility to either allow the camera to make all the decisions or to allow me to have complete manual control;

(4) that the camera was compatible with my existing camera gear.

Another plus of this camera is its ability to capture HD video.

But the last time I was in the field, which was May 2022 and my first trip abroad after the COVID pandemic, I left my trusted D810 at home and relied on my iPhone 11 Pro. This was something of an experiment.

Most of us still take large digital SLR cameras into the field. But the cameras on phones are now so good that, in most circumstances, these will meet your needs and certainly be ideal for capturing your field sketches. The panorama mode on the iPhone is especially useful for capturing big-picture landscapes.

Most digital cameras will record the location of each photo, especially if you are using a smartphone. But it is always worth noting the photos you have taken on your sketch – "panorama photograph," "detailed of this part of the outcrop," etc.

Please remember to save your photos to the cloud or your computer. I use Dropbox and iCloud as additional backup insurance.

Are Apple iPhones and other smartphones 'good enough'? Absolutely!

Which camera you use is as much about your budget and experience as anything else.

In choosing your camera, the best advice is to list the key features you need, such as sensor resolution, size, and price. Then, check this list against what is on offer. There is a considerable amount of help now available online. YouTube has a range, but I can recommend Ken Rockwell's excellent review site, https://kenrockwell.com/index.htm, or Digital Photography Review, https://www.dpreview.com/. I have used both in the past, especially Ken's website.

Once you have a shortlist, there is nothing better than going into a store, getting the 'feel' of the cameras on your list, and making a decision from this. You can then also get the advice of the experts in the store.

If the price is an issue, why not check second-hand deals from reputed camera stores?

My go-to DSLR is a Nikon D810 (https://www.dpreview.com/products/nikon/slrs/nikon_d810/specifications), which I have now had since about 2015. This is a great camera, but relatively large and heavy.

My decision here was based on several criteria:

(1) I needed a high-resolution sensor because I was using the photos for professional applications, and I already knew that I would need to zoom into a photo and crop it to get the images I wanted;

(2) a camera that was robust and weatherproofed (essential given where I take it);

(3) one that would give me the flexibility to either allow the camera to make all the decisions or to allow me to have complete manual control;

(4) that the camera was compatible with my existing camera gear.

Another plus of this camera is its ability to capture HD video.

But the last time I was in the field, which was May 2022 and my first trip abroad after the COVID pandemic, I left my trusted D810 at home and relied on my iPhone 11 Pro. This was something of an experiment.

Most of us still take large digital SLR cameras into the field. But the cameras on phones are now so good that, in most circumstances, these will meet your needs and certainly be ideal for capturing your field sketches. The panorama mode on the iPhone is especially useful for capturing big-picture landscapes.

Most digital cameras will record the location of each photo, especially if you are using a smartphone. But it is always worth noting the photos you have taken on your sketch – "panorama photograph," "detailed of this part of the outcrop," etc.

Please remember to save your photos to the cloud or your computer. I use Dropbox and iCloud as additional backup insurance.

Are Apple iPhones and other smartphones 'good enough'? Absolutely!

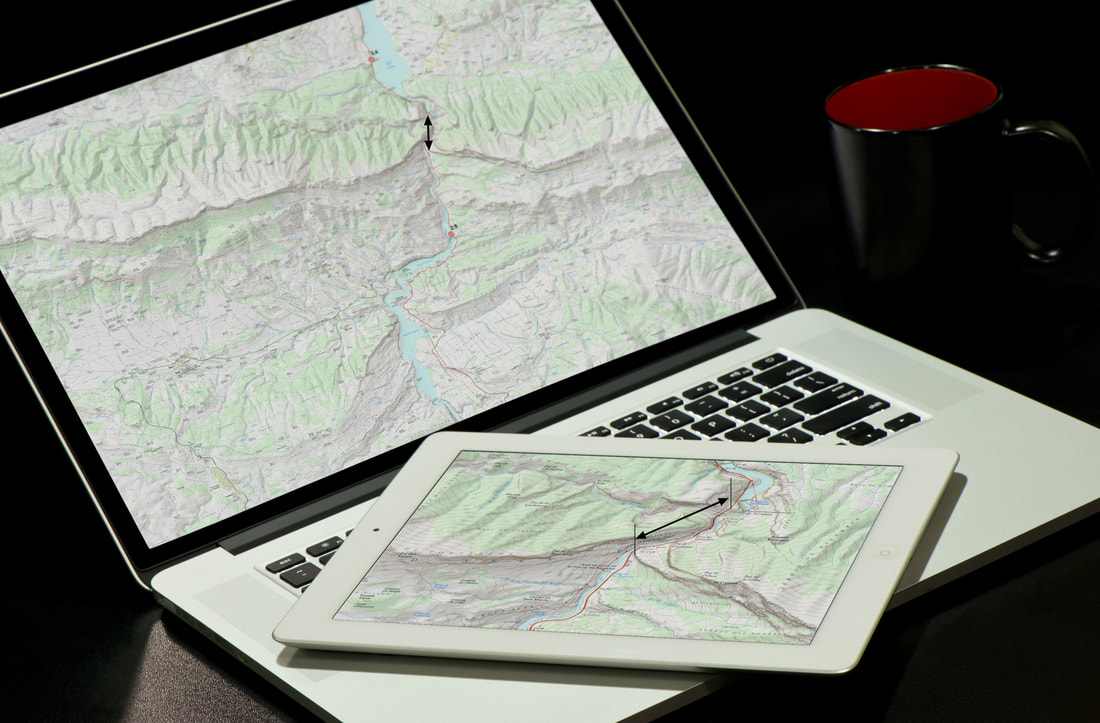

2. GPS

The Someta Geotagger GPS attached to a Nikon DSLR. These are great little devices. However, please remember that you will need one specifically designed for your camera.

Smartphones will have a GPS or WiFi-based locator built in. Depending on where in the field you are, this may or may not be adequate. However, if you are out in the 'boonies,' you may need a dedicated GPS, such as the Garmin GPSMAP 64s (https://buy.garmin.com/en-GB/GB/p/140022).

There are also GPS units that will fit onto your DSLR camera. Most camera brands will have their branded accessories.

I use a Solmeta Geotagger (http://www.solmeta.com/index.php/Product/show/id/2), which I have found to be excellent for the price. These will drain your camera battery, although not excessively so from experience (I can leave the GPS on automatic and only have to charge the batteries on my Nikon every few days, even after near-constant daily use). My only grumble with the Geotagger is that although it fits onto the flash shoe easily, it also tends to slide off easily as well. It would be great if there were a locking device of some form.

If your DSLR has Bluetooth connectivity, you may also be able to link the GPS location information from your smartphone to the camera.

There are also GPS units that will fit onto your DSLR camera. Most camera brands will have their branded accessories.

I use a Solmeta Geotagger (http://www.solmeta.com/index.php/Product/show/id/2), which I have found to be excellent for the price. These will drain your camera battery, although not excessively so from experience (I can leave the GPS on automatic and only have to charge the batteries on my Nikon every few days, even after near-constant daily use). My only grumble with the Geotagger is that although it fits onto the flash shoe easily, it also tends to slide off easily as well. It would be great if there were a locking device of some form.

If your DSLR has Bluetooth connectivity, you may also be able to link the GPS location information from your smartphone to the camera.

3. Camera straps

If you are using a DSLR and are in the habit of having the camera constantly at hand, then a good camera strap is essential. I use the Blackrapid Sport Breath strap (http://www.blackrapid.com/Sport-Breathe), which fits and locks into the base of the camera body. This is extremely comfortable, with the exception of the "underarm stabilizer" strap that fits under your armpit and is a pain, literally. I removed it without noticing any problems.

For your smartphone, a pocket will do!

For your smartphone, a pocket will do!

4. Photographic Scales

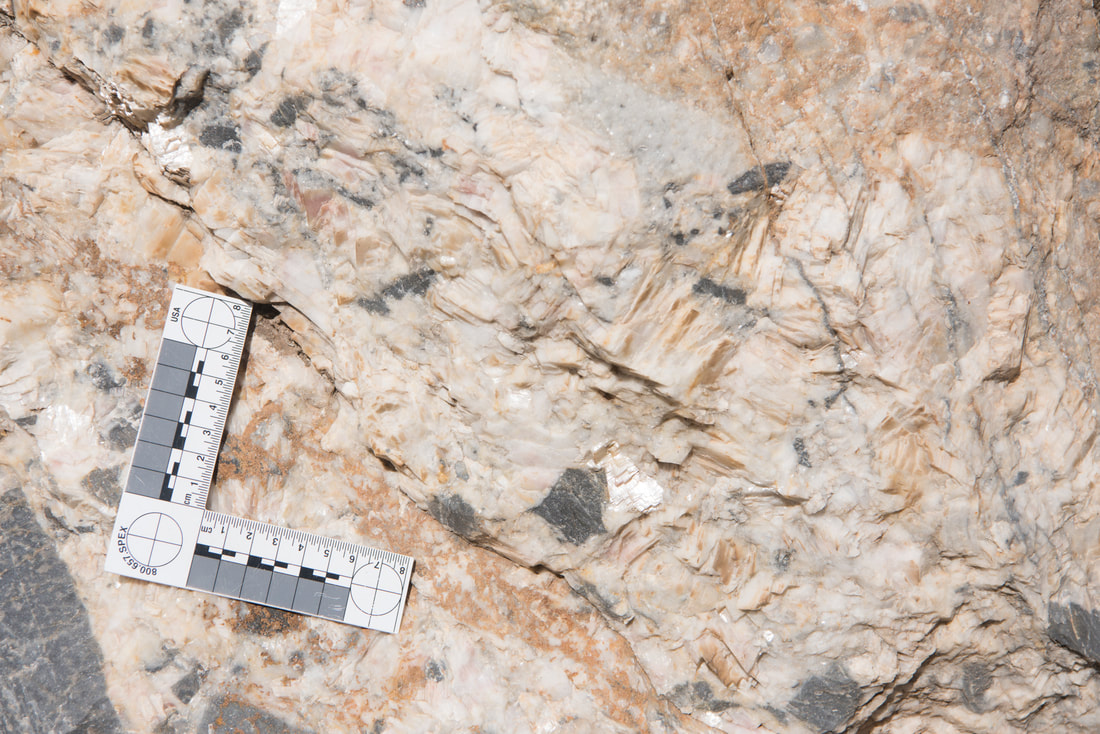

Scales are important. Coins, pencils, and lens caps are all very well and good and look nice and retro in a presentation, but they all vary in size. Today it is easy to buy a scale from the USGS, other geological stores, or, as I do, from a crime scene supplier. I have a set for different feature sizes to reflect the different extents of photos. What is useful for close-up photography is some indication of distortion on the scale - a circle divided into quarters.

Alligatorid fossil jaw from the Eocene Washakie Basin, Wyoming. The scale here is a US quarter piece (out of focus – another thing to consider when using scales) in the bottom right. Coins were a standard scale in field photography but suffered from several limitations, (1) they vary in size, (2) they are highly reflective, which can cause exposure problems, (3) should the coin be head side up (in the UK all coins had the Queen's head, so which coin was in the photograph was not always clear)and always top up in the photograph?

Mineral vein associated with brittle deformation in Devonian carbonates, Gistain, central Pyrenees. Here using a right-angle scale, with a circle that can be used to assess photographic distortion of the image.

5. Memory Cards, Hard-drives, and Cases

Memory cards now come in various formats for DSLR cameras, from SD, mini SD, XD, and compact flash (CF). But, of course, what you will need depends on your camera.

There are even more brands to choose from. I use SanDisk SD and CF cards and have had no major problems with these.

SanDisk Extreme PRO 32 GB SDHC Memory Card, Up to 95 MB/s, Class 10, U3, V30

How many cards you buy and which brand will also depend on your budget, as with so much else in today's blog guide.

Although memory card technology is relatively tried and tested, and problem cards are rare, I tend not to use anything bigger than a 64GB card. This mitigates the risks due to card failure and/or card loss.

An alternative approach is to download directly to a portable hard drive in the field.

Whatever storage system you use, you can further mitigate the risk of loss by uploading your photos to the cloud or backup device each evening. With the ready availability of cloud storage and access to WiFi, you should be able to do this relatively easily.

This is where smartphones can be handy if this is your primary photographic tool by having photos uploaded to the cloud whenever in 4G or WiFi range. The only issue here is the data usage cost, so check your provider's data usage policy and charges.

There are even more brands to choose from. I use SanDisk SD and CF cards and have had no major problems with these.

SanDisk Extreme PRO 32 GB SDHC Memory Card, Up to 95 MB/s, Class 10, U3, V30

How many cards you buy and which brand will also depend on your budget, as with so much else in today's blog guide.

Although memory card technology is relatively tried and tested, and problem cards are rare, I tend not to use anything bigger than a 64GB card. This mitigates the risks due to card failure and/or card loss.

An alternative approach is to download directly to a portable hard drive in the field.

Whatever storage system you use, you can further mitigate the risk of loss by uploading your photos to the cloud or backup device each evening. With the ready availability of cloud storage and access to WiFi, you should be able to do this relatively easily.

This is where smartphones can be handy if this is your primary photographic tool by having photos uploaded to the cloud whenever in 4G or WiFi range. The only issue here is the data usage cost, so check your provider's data usage policy and charges.

6. Battery Packs

If you are using your iPhone or Samsung phone for photography and especially if taking video, then you should invest in a battery pack that you can take with you in case your phone needs a recharge in the field. I use an Anker powerbank.

7. Lenses

If you have a DSLR, this opens up a range of lens options. But, again, this will be limited by budget and packing space if you are traveling. A good quality wide-angle to-zoom lens such as a 24-70mm is a good balance for most field applications. You might also want to consider a macro lens if you expect to do much close-up work. If so, then you will also want a suitable lighting system.

In the past, outcrop photos usually necessitated the use of a wide-angle lens, with the problems of distortion, but this is now mitigated by the ability to build panoramas. I use the 24mm in portrait mode with at least a 30% overlap. Some cameras and most phones will have an excellent automatic panorama generator, which is a helpful solution.

There may be occasions when you want to zoom into an outcrop distant from you. For example, I will sometimes take a 70-300mm with me if I have space, but this is heavy, and for long trips in the field this weight must be taken into consideration.

With high-resolution cameras, you can also zoom in by cropping during processing if you do not have the necessary telephoto lens. With megapixel sizes of 32MP now very common on DSLRs, this is more than feasible.

In the past, outcrop photos usually necessitated the use of a wide-angle lens, with the problems of distortion, but this is now mitigated by the ability to build panoramas. I use the 24mm in portrait mode with at least a 30% overlap. Some cameras and most phones will have an excellent automatic panorama generator, which is a helpful solution.

There may be occasions when you want to zoom into an outcrop distant from you. For example, I will sometimes take a 70-300mm with me if I have space, but this is heavy, and for long trips in the field this weight must be taken into consideration.

With high-resolution cameras, you can also zoom in by cropping during processing if you do not have the necessary telephoto lens. With megapixel sizes of 32MP now very common on DSLRs, this is more than feasible.

8. Tripods

A tripod is helpful but not essential, given the greater control digital cameras have over ISO, without the increase in graininess that blighted film.

For travel, I use the lightweight Manfrotto Beefree. This tripod is great, and I can highly recommend this. However, this may not be suitable if you have a large DSLR and lens.

These lightweight travel tripods are not the cheapest (and seem to have gone up in price substantially since I bought mine) so do check out the second-hand market and sales.

If you are worried about a lightweight tripod being affected by strong winds, especially if you are in the mountains, then consider using your backpack to further stabilize a tripod by hanging it below the head. This provides more mass.

The alternative to these lightweight travel tripods is a full-size professional tripod, but these will increase the weight you carry in the field, so bear this in mind.

A few years back, one of my brothers gifted me a smartphone clamp for my iPhone. Brilliant! I use this fitted to a Manfrotto MVH400AH Befree Live Fluid Head and the BeeFree tripod for shooting my new series of videos.

For travel, I use the lightweight Manfrotto Beefree. This tripod is great, and I can highly recommend this. However, this may not be suitable if you have a large DSLR and lens.

These lightweight travel tripods are not the cheapest (and seem to have gone up in price substantially since I bought mine) so do check out the second-hand market and sales.

If you are worried about a lightweight tripod being affected by strong winds, especially if you are in the mountains, then consider using your backpack to further stabilize a tripod by hanging it below the head. This provides more mass.

The alternative to these lightweight travel tripods is a full-size professional tripod, but these will increase the weight you carry in the field, so bear this in mind.

A few years back, one of my brothers gifted me a smartphone clamp for my iPhone. Brilliant! I use this fitted to a Manfrotto MVH400AH Befree Live Fluid Head and the BeeFree tripod for shooting my new series of videos.

This is the setup I use for videos. An iPhone connected to a Sennheiser MKE 200 directional microphone on a Manfrotto BeeFree tripod. For narration, I use a Røde SmartLav+ lapel microphone rather than the Sennheiser.

9. Lighting

With most DSLRs and phone cameras, low lighting is much less of an issue than it was, say, when I made my undergraduate field trips 30+ years ago (ok, perhaps nearer 40 years ago). By increasing the ISO on your camera, you can still get relatively sharp results. Of course, this will depend on your camera, and some are better than others.

Alternative options include long shutter speeds with the camera on a tripod or using artificial lighting.

If you are doing this professionally, I am sure you will already have a range of flash guns you will take. Although for everyday field work, this will be an additional weight to carry – and a drain on your battery supply!

If you plan on taking close-ups of rock surfaces, you might consider a macro (ring) flash unit that fits on the front of your DSLR lens. A range of 3rd party units is available (check out Amazon or Wex Photo).

Alternative options include long shutter speeds with the camera on a tripod or using artificial lighting.

If you are doing this professionally, I am sure you will already have a range of flash guns you will take. Although for everyday field work, this will be an additional weight to carry – and a drain on your battery supply!

If you plan on taking close-ups of rock surfaces, you might consider a macro (ring) flash unit that fits on the front of your DSLR lens. A range of 3rd party units is available (check out Amazon or Wex Photo).

10. Camera bags

The problem is that you will be going into field areas with rocks, which by definition, are not good for cameras. So you need to ensure that when carrying a camera, it has plenty of protection but is also easily accessible. I have traditionally used a Lowepro camera bag, and I can recommend Lowepro in general. However, a few years back, I tried a Crumpler bag. Bright red and extremely simple (one compartment), this has actually ended up being my favorite bag for day trips in the field. However, it must be said that it is not ideal for major hiking expeditions when I return to the Lowepros!

11. Software

Most smartphones will include their own software where you can run a selection of processing. For advanced processing, consider using software such as Adobe Lightroom, which to me, is the best software for post-production and managing digital photographs. There are student pricing solutions available. If you have Lightroom, you won't need any other software (it now even has a panorama building extension).

12. Notebooks

Your camera is only one part of your toolkit. A camera does not replace the need for a notebook and pencils; indeed, you will want to keep track of your photographs in your notebook!

My personal notebook preference is still the Chartwell 2006Z top-opening survey book . Although this lacks the waterproofing and useful look-up information at the back of the Rite in the Rain Geological Notebooks, I particularly like the fact that I can open up the Chartwell notebook in landscape orientation, which gives me two pages for sketches. The 2006Z version also has two parallel lines, which provide great reference lines for sketching and logging when in portrait view.

Ensure that your notebook is a bright color in case you leave it on an outcrop and you need to find it again from a distance. Bright yellow or orange are easier to spot!

The general guidance from most field geologists is to use a pencil in the field and to generate an "inked-in version" each evening. This has the benefit of ensuring you have two copies of your notes. However, with good-quality cameras on most smartphones today, an alternative or additional safeguard is to photograph your day's notes and save this to the cloud.

My personal notebook preference is still the Chartwell 2006Z top-opening survey book . Although this lacks the waterproofing and useful look-up information at the back of the Rite in the Rain Geological Notebooks, I particularly like the fact that I can open up the Chartwell notebook in landscape orientation, which gives me two pages for sketches. The 2006Z version also has two parallel lines, which provide great reference lines for sketching and logging when in portrait view.

Ensure that your notebook is a bright color in case you leave it on an outcrop and you need to find it again from a distance. Bright yellow or orange are easier to spot!

The general guidance from most field geologists is to use a pencil in the field and to generate an "inked-in version" each evening. This has the benefit of ensuring you have two copies of your notes. However, with good-quality cameras on most smartphones today, an alternative or additional safeguard is to photograph your day's notes and save this to the cloud.

Final Thoughts

As I said at the outset of this article, what photographic equipment you use in the field is very much down to your budget and personal preference.

Is an iPhone or other smartphone good enough for most student field trips? Absolutely!

Whether you use a DSLR or phone, remember about lighting, scales, and the need for context, a 'big picture' shot to capture the context and details of the rock units, fossils, and structures.

I hope this short article has been helpful. I would love to learn about your field kit experiences and recommendations.

Have fun!

Is an iPhone or other smartphone good enough for most student field trips? Absolutely!

Whether you use a DSLR or phone, remember about lighting, scales, and the need for context, a 'big picture' shot to capture the context and details of the rock units, fossils, and structures.

I hope this short article has been helpful. I would love to learn about your field kit experiences and recommendations.

Have fun!

A pdf version of this blog is available for download here

What can the Cenomanian-Turonian tell us about the carbon cycle?

Photo: Mowry Shale overlain by the Frontier Sandstone. North of Vernal, Utah.

Full conference information is available here: https://sepm.org/gcssepm-perkins-rosen-conference

This December, the GCSSEPM Foundation will convene the 38th Annual Perkins-Rosen Research Conference on the subject of the "The Cenomanian-Turonian Stratigraphic Interval Across the Americas: Argentina to Alaska". December 5-7, 2022, Houston, Texas.

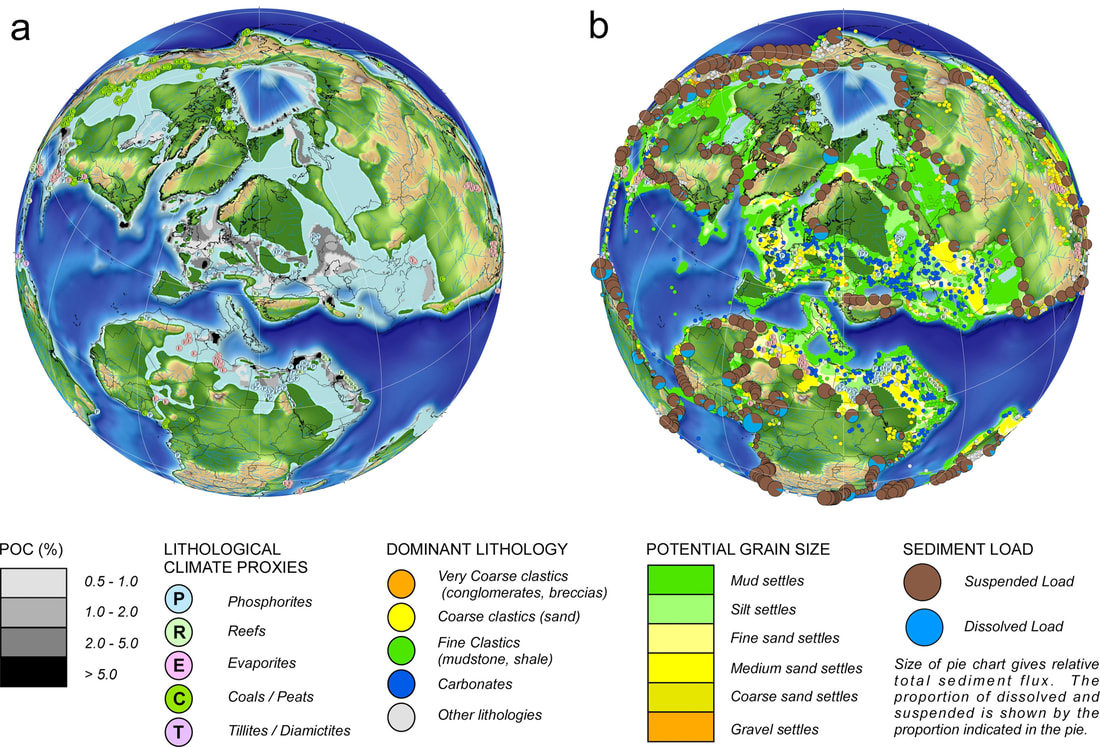

The Cenomanian-Turonian (c.100.5-89.8 Ma, Late Cretaceous) represents a stratigraphic time interval that has intrigued me for much of my career. It encompasses periods of widespread carbon-rich sediment deposition, resulting in the sequestration of large volumes of organic carbon. The coincidence of these organic-rich rocks with a dramatic carbon isotopic excursion (Oceanic Anoxic Event - OAE-2) and the highest sea-levels of the Phanerozoic have led to hypotheses that these attributes are the result of complex interactions between the bio-, hydro- and geo-spheres that are unique to this time. But is this true? What really is going on? What was the ocean system doing? Was this a single event? Was it truly global or even globally synchronous? So many questions!

Long the focus of interest from hydrocarbon explorationists looking to understand source facies and unconventional resources, the Cenomanian-Turonian has much to tell us about the Earth System and its workings, especially the carbon cycle.

This research conference will bring together experts and data from both Industry, Academia and government to facilitate dialogue and discussion about this intriguing time interval. Oral and poster presentations will examine a wide range of topics, and there will also be a related core workshop where you can see what this interval looks like in the rock record.

There will also be a related core workshop you can register for, where you can see what this interval looks like in the rock record.

If you would like to learn more about this research conference, you can find further information here: https://sepm.org/gcssepm-perkins-rosen-conference

For information about sponsorship opportunities, please get in touch directly with Dr. John Suter, Executive Director GCSSEPM Foundation at gcssemp1@gmail.com.

And of course, you can also contact me at paul.markwick@knowing.earth

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Equinor, who are kindly hosting this event.

The Cenomanian-Turonian (c.100.5-89.8 Ma, Late Cretaceous) represents a stratigraphic time interval that has intrigued me for much of my career. It encompasses periods of widespread carbon-rich sediment deposition, resulting in the sequestration of large volumes of organic carbon. The coincidence of these organic-rich rocks with a dramatic carbon isotopic excursion (Oceanic Anoxic Event - OAE-2) and the highest sea-levels of the Phanerozoic have led to hypotheses that these attributes are the result of complex interactions between the bio-, hydro- and geo-spheres that are unique to this time. But is this true? What really is going on? What was the ocean system doing? Was this a single event? Was it truly global or even globally synchronous? So many questions!

Long the focus of interest from hydrocarbon explorationists looking to understand source facies and unconventional resources, the Cenomanian-Turonian has much to tell us about the Earth System and its workings, especially the carbon cycle.

This research conference will bring together experts and data from both Industry, Academia and government to facilitate dialogue and discussion about this intriguing time interval. Oral and poster presentations will examine a wide range of topics, and there will also be a related core workshop where you can see what this interval looks like in the rock record.

There will also be a related core workshop you can register for, where you can see what this interval looks like in the rock record.

If you would like to learn more about this research conference, you can find further information here: https://sepm.org/gcssepm-perkins-rosen-conference

For information about sponsorship opportunities, please get in touch directly with Dr. John Suter, Executive Director GCSSEPM Foundation at gcssemp1@gmail.com.

And of course, you can also contact me at paul.markwick@knowing.earth

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Equinor, who are kindly hosting this event.

Mapping the Earth’s structural framework

Paul Markwick

As geologists, we all ‘know’ what a structural map is – the map representation of the geometry and kinematics of folds and faults. Nothing could be simpler. So, when John Jacques and I established the Petroleum Systems Evaluation Group (PSEG) at Getech back in 2004, building the structural framework for each of our new regional studies seemed the least of our worries. But, to our surprise, we were wrong. It turned out that not every structural geologist sees structural mapping in the same way. And as for the geophysicist view of structures… well, that is a story for another day. This was to cost us much time and monies. The question is, why?

Faults and folds are amongst the clearest expressions of past tectonics that we can observe directly.

The graphical representation of these features depends on application and scale.

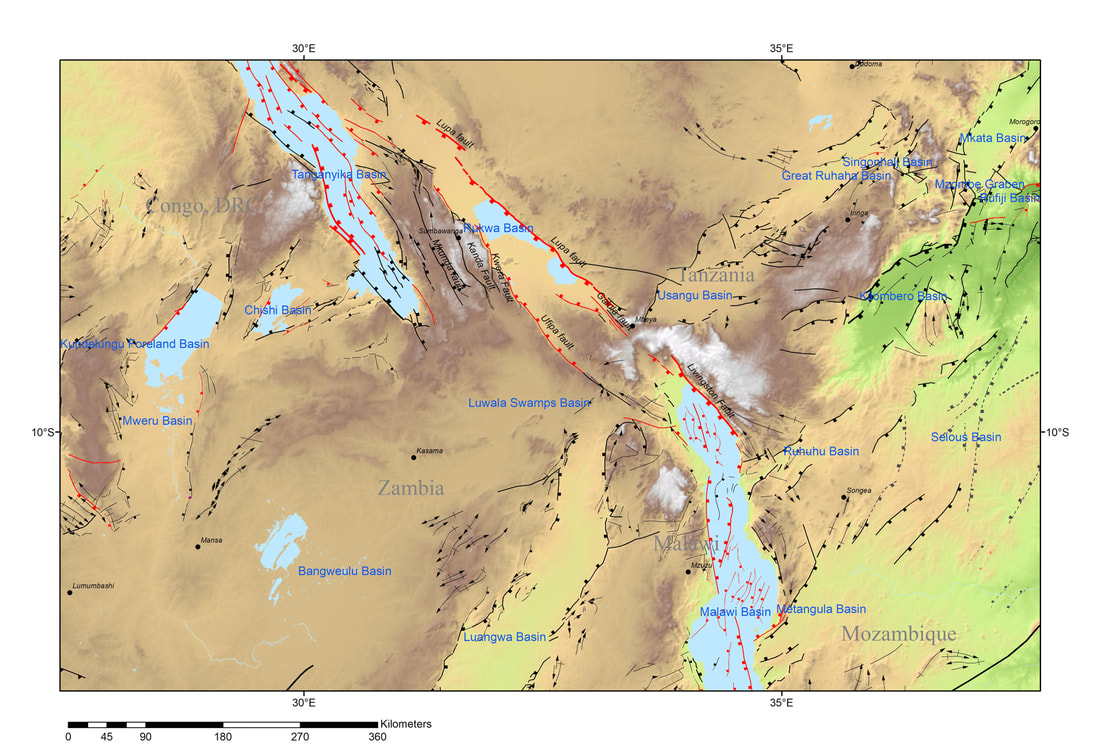

On geological maps, structural elements are usually shown by lines. These mark the trace of the intersection of each structural feature with the Earth’s surface. Kinematics are represented graphically by a commonly applied symbology (Figure 1). In many structural maps, sub-surface features are also represented by extending their top trace vertically until it intersects the current land surface (in our databases, we use an attribute to distinguish between features exposed at the surface and those in the sub-surface). This combination of line features is what John and I had in mind, given our focus on New Ventures exploration and how we would use the framework: to define the crustal architecture, build tectonic models and then develop paleogeographies.

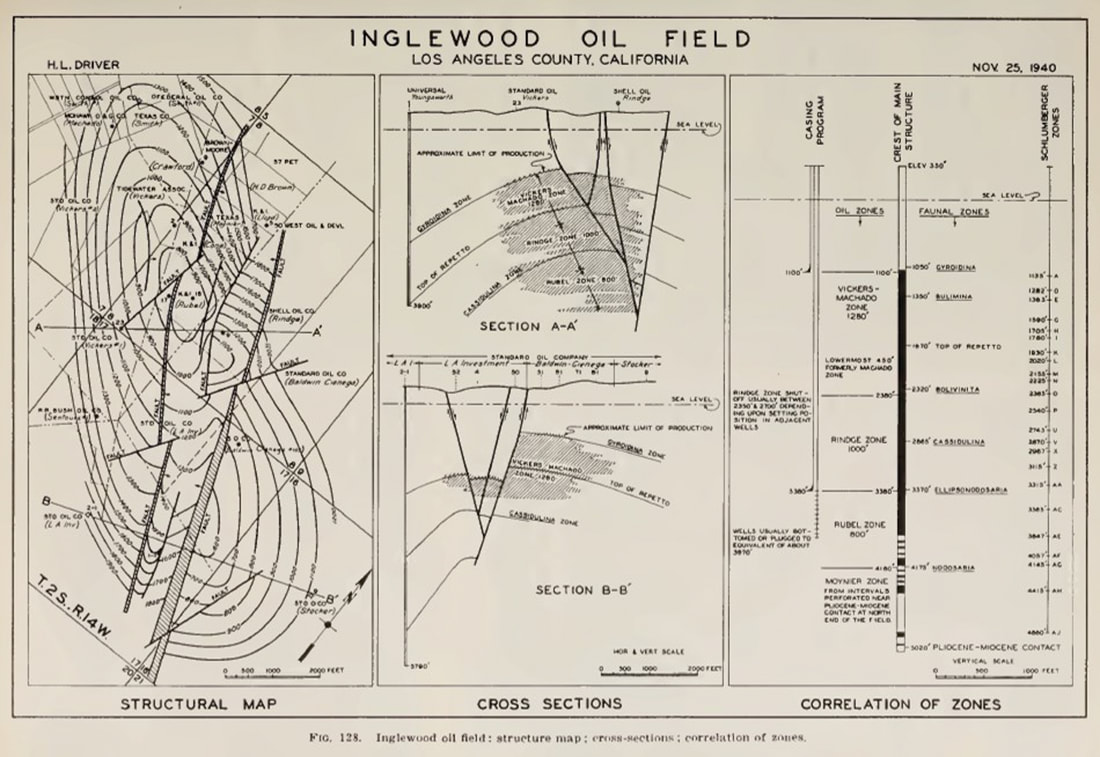

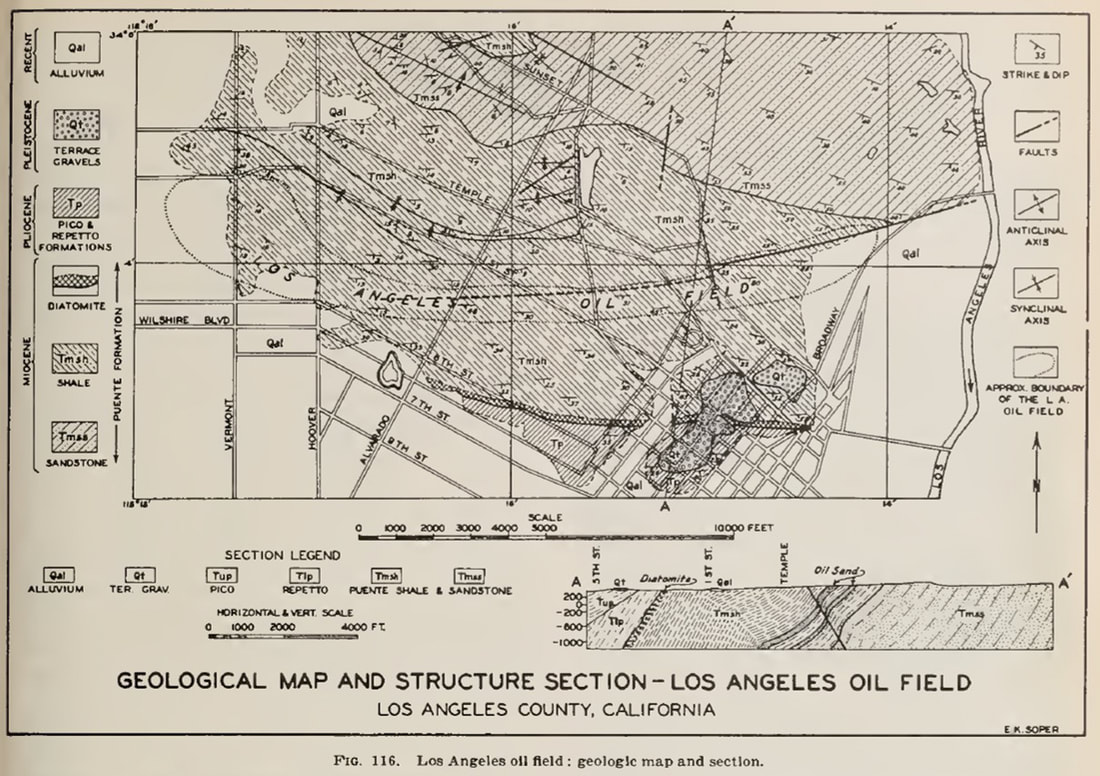

When we get to prospect scale (Figure 2), it becomes essential to consider the 3D geometry to calculate volumetrics, investigate fault closure, trapping mechanisms, migration pathways, etc. To this end, we build structural contour maps and show our faults at the surface as polygons representing the dip and throw of each fault plane with depth.

The graphical representation of these features depends on application and scale.

On geological maps, structural elements are usually shown by lines. These mark the trace of the intersection of each structural feature with the Earth’s surface. Kinematics are represented graphically by a commonly applied symbology (Figure 1). In many structural maps, sub-surface features are also represented by extending their top trace vertically until it intersects the current land surface (in our databases, we use an attribute to distinguish between features exposed at the surface and those in the sub-surface). This combination of line features is what John and I had in mind, given our focus on New Ventures exploration and how we would use the framework: to define the crustal architecture, build tectonic models and then develop paleogeographies.

When we get to prospect scale (Figure 2), it becomes essential to consider the 3D geometry to calculate volumetrics, investigate fault closure, trapping mechanisms, migration pathways, etc. To this end, we build structural contour maps and show our faults at the surface as polygons representing the dip and throw of each fault plane with depth.

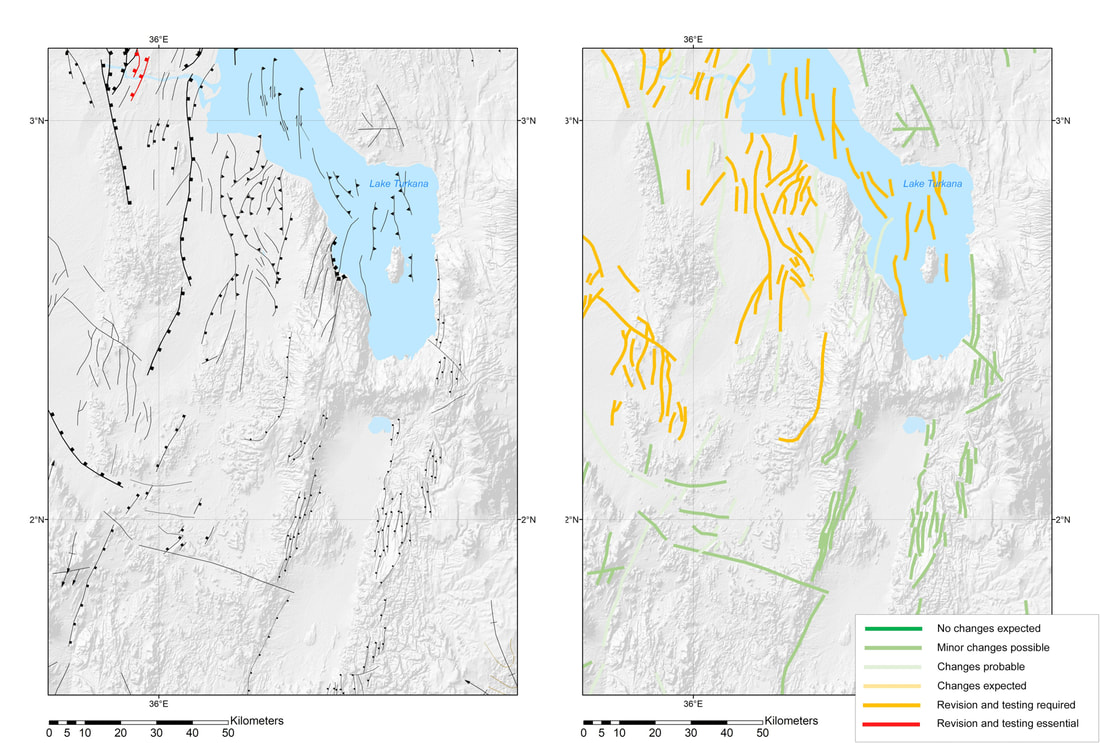

Figure 1. An example of the data in our Structural Elements database for the area around Rukwa and northern Malawi. Features are represented by lines that mark the trace of faults at the surface (or projected up from their highest expression for subsurface faults) and axes of folds. When I think of a structural map in New Ventures exploration or most of my academic work, this is what I think of.

Figure 2. An example of a prospect-scale map, in this case, a vintage map of the Inglewood oil field in California. The structural map (left) includes structural contours and faults as polygons to show the geometry of dip and throw (Jenkins, 1943)

This difference due to application and scale is nothing new. It was also not the cause of the problems that John and I faced.

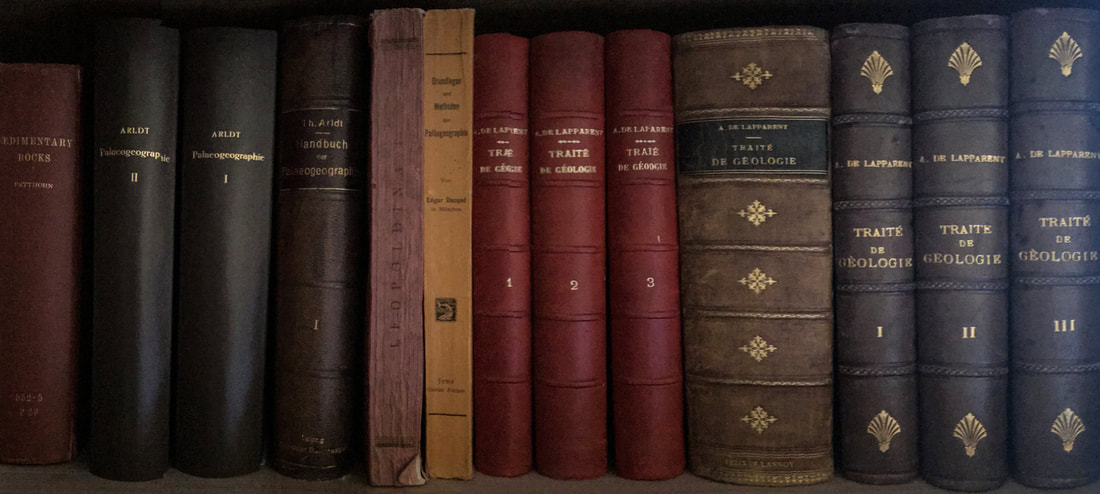

I have been thinking about this recently. Primarily because I am once again building a global crustal architecture geospatial database, this time armed with 30 years of experience, much older and hopefully a little wiser. But also, because I am writing a new paper on the history of geological representation.

Much has changed since 2004. For example, our understanding of the complexity of crustal architecture has developed substantially in the last decade due to the increased availability of ultra-deep, 2D seismic data along many of the world’s continental margins (Manatschal, Sutra and Péron-Pinvidic, 2010; Péron-Pinvidic and Manatschal, 2009). Databases and map representations need to take account of these advances.

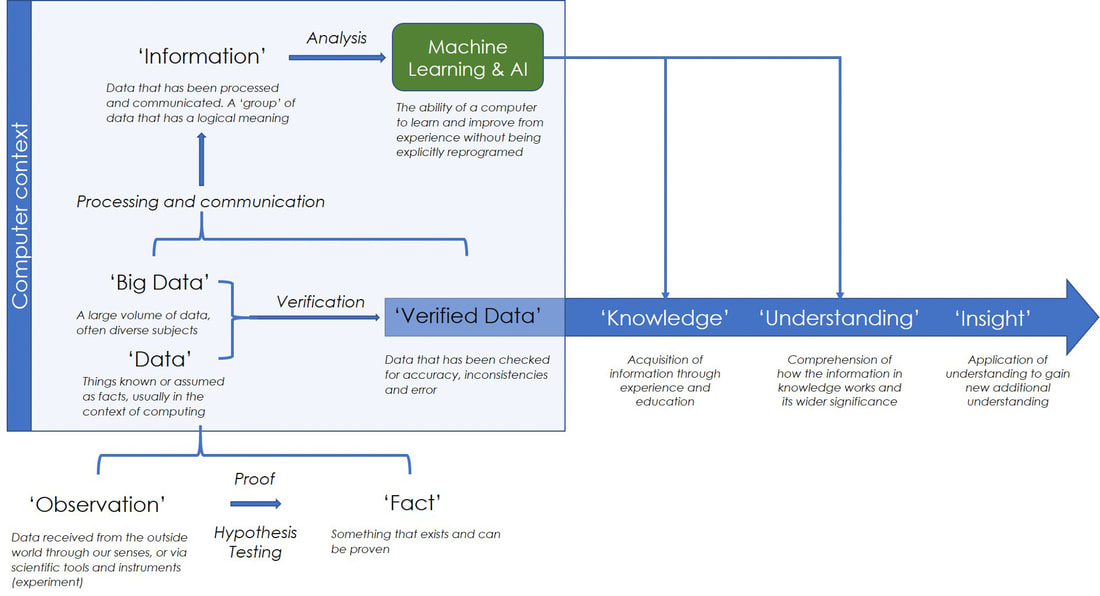

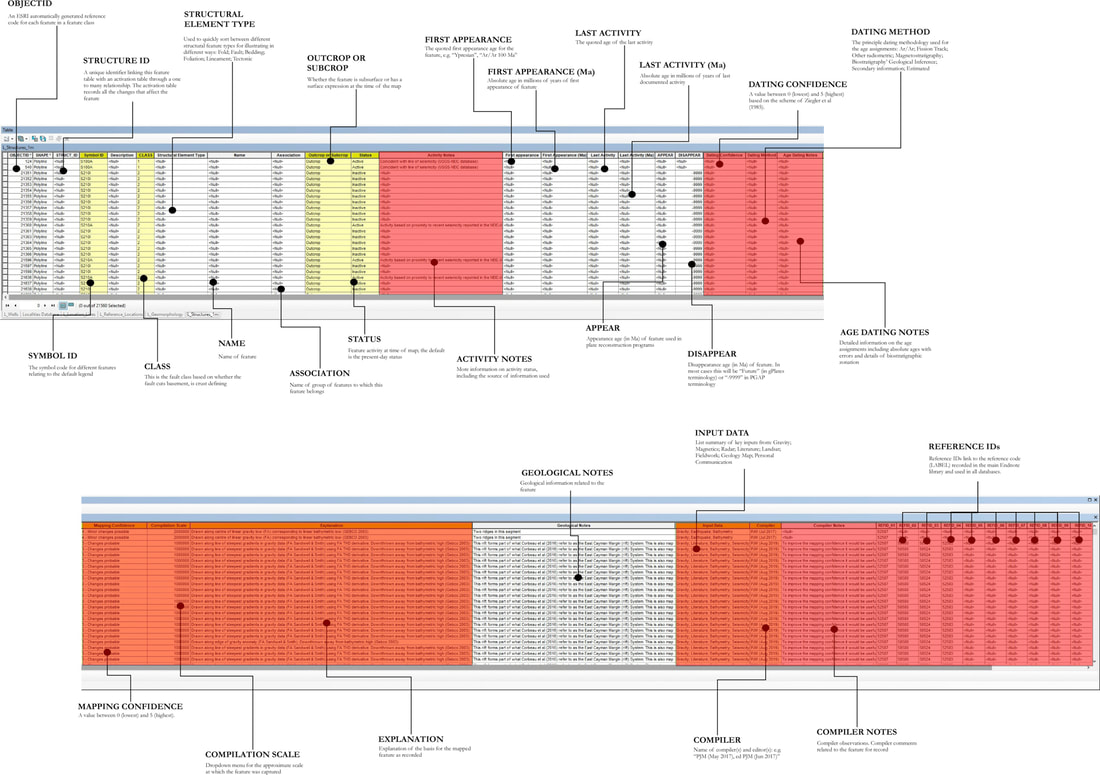

The new databases I am working on are more systematic, more integrated, more detailed, and based on more data. The workflow begins with the Structural Elements database, forming the framework around which all the other elements are built. Hence the reference to a structural ‘framework’. So, getting this database right, or as correct as possible, is critical because everything else hangs from this. Everything from the crustal facies and geodynamics databases to how we define our sedimentary basins and their depositional fill, and ultimately to plate reconstructions, paleogeography, and paleolandscapes.

In revisiting this whole process and detailing the mapping workflow, I realized that some questions need to be explicitly addressed from the outset if we are to get others, not least our staff, to know what we want. These questions include the following:

The answers to these are relatively straightforward once stated (answers at the end of the article) – operationally, these are now addressed in the extensive documentation created for each database.

In this blog, I want to look at the history of structural mapping as a way to try and explain the problems that John and I encountered. Because by looking at this history, we can hopefully get closer to answering the fundamental question: What is a structural map?

I have been thinking about this recently. Primarily because I am once again building a global crustal architecture geospatial database, this time armed with 30 years of experience, much older and hopefully a little wiser. But also, because I am writing a new paper on the history of geological representation.

Much has changed since 2004. For example, our understanding of the complexity of crustal architecture has developed substantially in the last decade due to the increased availability of ultra-deep, 2D seismic data along many of the world’s continental margins (Manatschal, Sutra and Péron-Pinvidic, 2010; Péron-Pinvidic and Manatschal, 2009). Databases and map representations need to take account of these advances.

The new databases I am working on are more systematic, more integrated, more detailed, and based on more data. The workflow begins with the Structural Elements database, forming the framework around which all the other elements are built. Hence the reference to a structural ‘framework’. So, getting this database right, or as correct as possible, is critical because everything else hangs from this. Everything from the crustal facies and geodynamics databases to how we define our sedimentary basins and their depositional fill, and ultimately to plate reconstructions, paleogeography, and paleolandscapes.

In revisiting this whole process and detailing the mapping workflow, I realized that some questions need to be explicitly addressed from the outset if we are to get others, not least our staff, to know what we want. These questions include the following:

- Should the maps be based on map interpretations published by other people (secondary data) or interpreted from primary data?

- Should we assume that existing interpretations are correct?

- What density of structures should be mapped?

- Should only features with a direct link to petroleum be recorded?

- Should the maps only show the present-day geometry of features or show the past geometry at a time of the compilers' choosing/interest?

- Should the maps be schematic with segments linked into a continuous form (general pattern of faults and folds) or only what is ‘observed’ (actual or as close to reality as possible)?

The answers to these are relatively straightforward once stated (answers at the end of the article) – operationally, these are now addressed in the extensive documentation created for each database.

In this blog, I want to look at the history of structural mapping as a way to try and explain the problems that John and I encountered. Because by looking at this history, we can hopefully get closer to answering the fundamental question: What is a structural map?

The ‘architecture’ of the Earth

When Thomas Sterry Hunt first described the process of making his paleogeographic maps in his 1873 paper (Hunt, 1873), he stressed the importance of first understanding the underlying “architecture [of the Earth]”

“The structure and arrangement of the materials of the earth’s crust, its architecture, as it were…”

In this, Hunt was likely influenced by his experience as an exploration geologist and how structure often dictated the distribution of oil – Hunt was one of the first to recognize the link between anticlinal structures and oil fields (Hunt, 1862).

Crustal ‘architecture’ is much more than mapping the structural ‘framework’ as a structural elements database. It encompasses all the crust. In reading back through the early 19th century literature, it is clear that when geologists referred to ‘structure’, they were using it in the same way as Hunt used [crustal] “architecture”. Indeed mapping faults and fold axes as lines developed relatively late in geology.

Folding and faulting showed how dynamic the Earth was. You only have to read Humboldt, Hutton, or Lyell to get a sense of this. But when these geologists came to map this deformation, the resulting ‘structure’ was defined by outcrop geometry in map view or bed orientation in sections, rather than by discrete fault lines and planes. The maps of Smith, for example, show outcrop geometries that define folds and faulted boundaries but do not show the fold axes or faults themselves. Similarly, his cross-sections.

So in this 19th-century view of a ‘structural map,’ we are not just representing the trace of fold axes or faults but the entire 3-dimensional crustal form. In terms of the databases I am building today, this would require three separate but related databases: (1) structural elements, which define the three-dimensional geometry of the rock volume, including folds and faults as a framework of line traces; (2) 'crustal' facies describing the geometry and composition/rheology of the lithosphere; and (3) bedrock geology, comprising the surface outcrop. We might add (4) igneous features; and (5) geodynamics, representing the dominant thermo-mechanical processes acting on the lithosphere. Both of these give additional information on the dynamic processes that generate the form.

“The structure and arrangement of the materials of the earth’s crust, its architecture, as it were…”

In this, Hunt was likely influenced by his experience as an exploration geologist and how structure often dictated the distribution of oil – Hunt was one of the first to recognize the link between anticlinal structures and oil fields (Hunt, 1862).

Crustal ‘architecture’ is much more than mapping the structural ‘framework’ as a structural elements database. It encompasses all the crust. In reading back through the early 19th century literature, it is clear that when geologists referred to ‘structure’, they were using it in the same way as Hunt used [crustal] “architecture”. Indeed mapping faults and fold axes as lines developed relatively late in geology.

Folding and faulting showed how dynamic the Earth was. You only have to read Humboldt, Hutton, or Lyell to get a sense of this. But when these geologists came to map this deformation, the resulting ‘structure’ was defined by outcrop geometry in map view or bed orientation in sections, rather than by discrete fault lines and planes. The maps of Smith, for example, show outcrop geometries that define folds and faulted boundaries but do not show the fold axes or faults themselves. Similarly, his cross-sections.

So in this 19th-century view of a ‘structural map,’ we are not just representing the trace of fold axes or faults but the entire 3-dimensional crustal form. In terms of the databases I am building today, this would require three separate but related databases: (1) structural elements, which define the three-dimensional geometry of the rock volume, including folds and faults as a framework of line traces; (2) 'crustal' facies describing the geometry and composition/rheology of the lithosphere; and (3) bedrock geology, comprising the surface outcrop. We might add (4) igneous features; and (5) geodynamics, representing the dominant thermo-mechanical processes acting on the lithosphere. Both of these give additional information on the dynamic processes that generate the form.

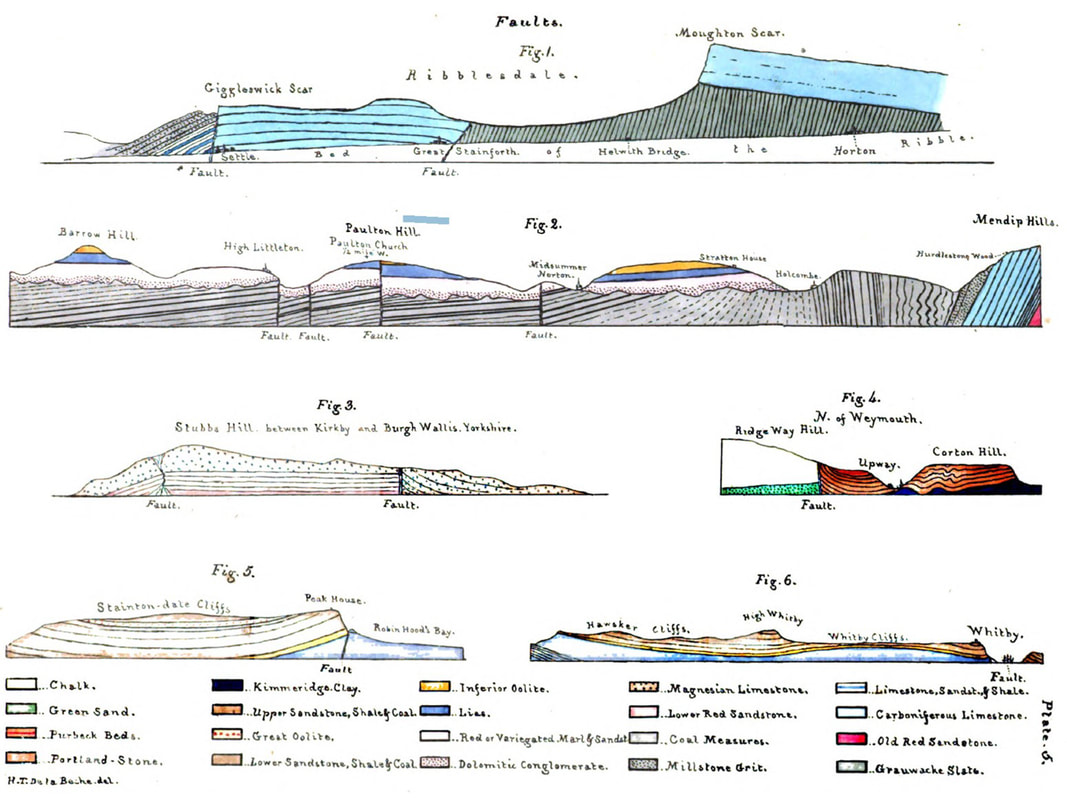

De La Beche and faults as lines

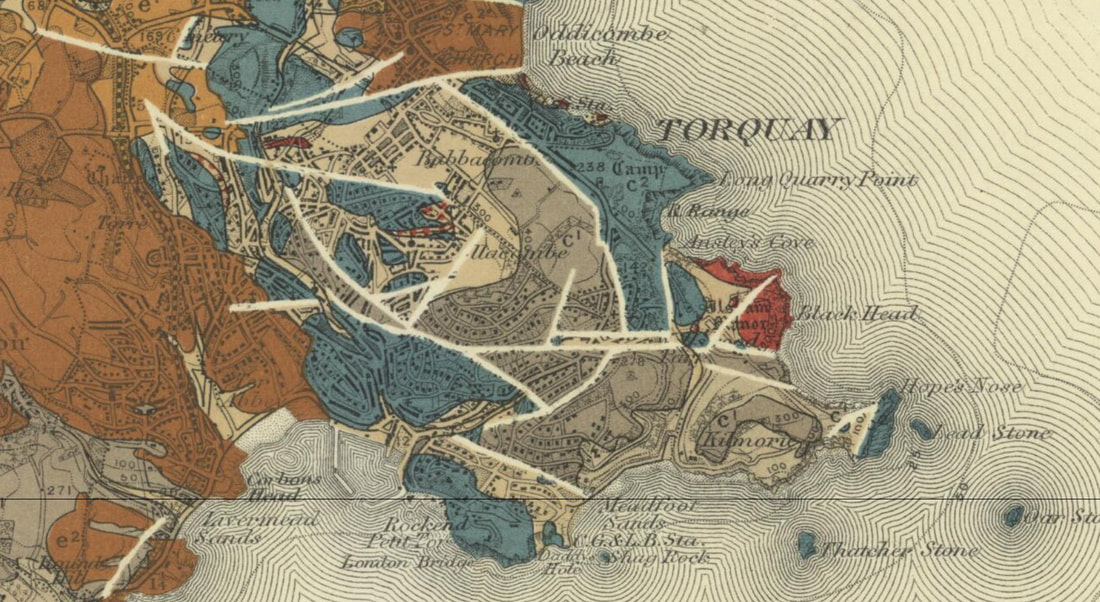

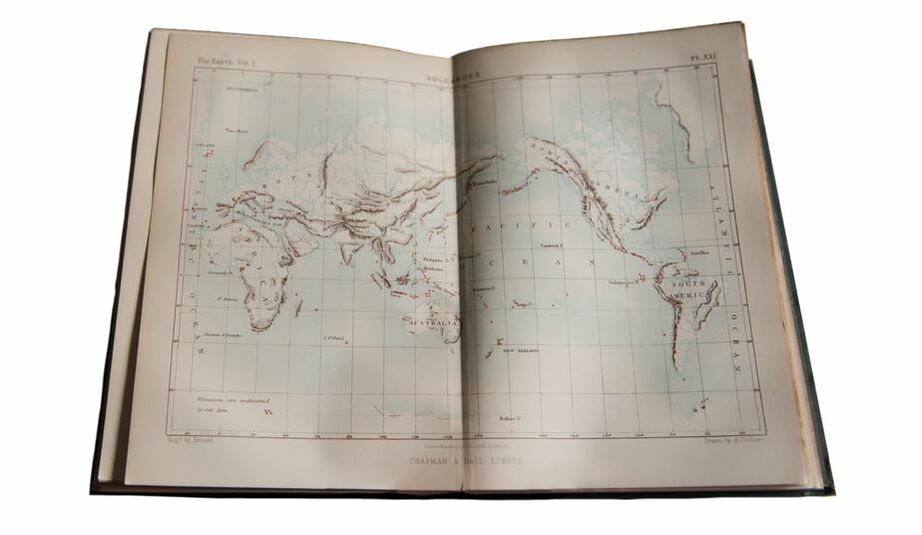

It was Henry De La Beche who explicitly showed faults as lines in his sections (De la Beche, 1830). These thick black lines in sections (Fig.3) were replaced in map view by thick white lines. This symbology continued to be used on British maps throughout the 19th century (Fig. 4). There was no differentiation between different types of faults.

But a search of 19th century maps suggests that the inclusion of fault traces was not universal. Even Élisee Reclus in his seminal work on global geography, did not show maps of major fault lines, although he did provide maps of the East African rift, showing the topographic fault scarps (“Line of Volcanic Fault” (Fig.104 in Reclus, 1876).

But a search of 19th century maps suggests that the inclusion of fault traces was not universal. Even Élisee Reclus in his seminal work on global geography, did not show maps of major fault lines, although he did provide maps of the East African rift, showing the topographic fault scarps (“Line of Volcanic Fault” (Fig.104 in Reclus, 1876).

Figure 3. Examples of faults shown in De la Beche cross-sections from various locations in the United Kingdom (De la Beche, 1830)

Figure 4. An example of mapped faults represented by white lines on this map of the Mendips by De la Beche (1845). British Geological Survey materials © UKRI (1845) http://www.largeimages.bgs.ac.uk/iip/mapsportal.html?id=1000027

John Wesley Powell and the Standardization of Geological Maps

The most significant change in structural mapping occurred in the 1880s, when John Wesley Powell, the second director of the newly formed USGS, started a drive to standardize map symbology and colors. In these maps, Powell explicitly showed structural elements (Powell, 1882), but like De la Beche, these were heavy black lines without associated markers. Powell also used dashed lines to show fault extents where the trace could not be discerned but was assumed to continue. Forty years earlier, De la Beche had also shown dashed fault lines on some of his maps, but had not explained what these meant in the legend; one assumes to show uncertainty like Powell:

“Fault lines (particularly when they are formation boundaries) shall be indicated when actually traced by somewhat heavy full lines in black; and when not actually traced, by similar broken lines, toward which the formation devices may blend or fade as circumstances seem to require.”

(Powell, 1890)

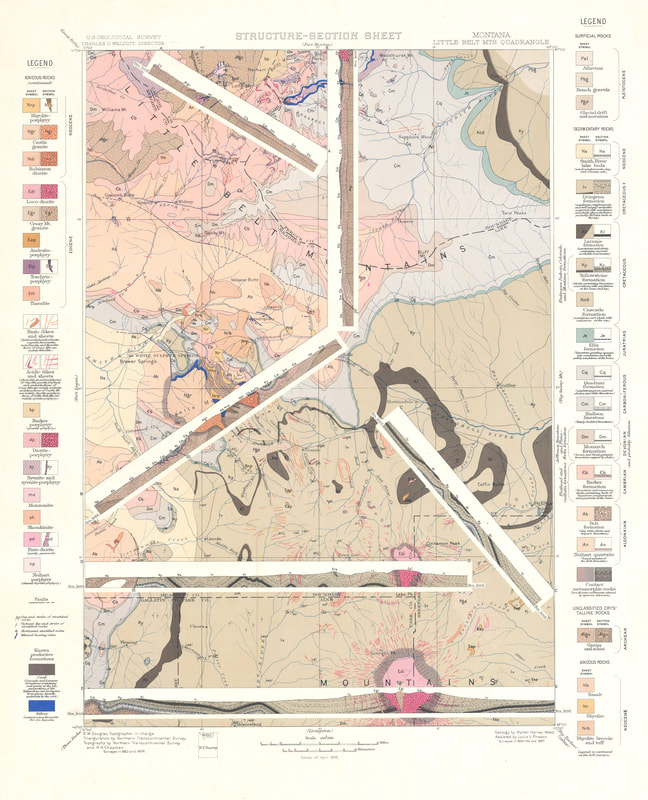

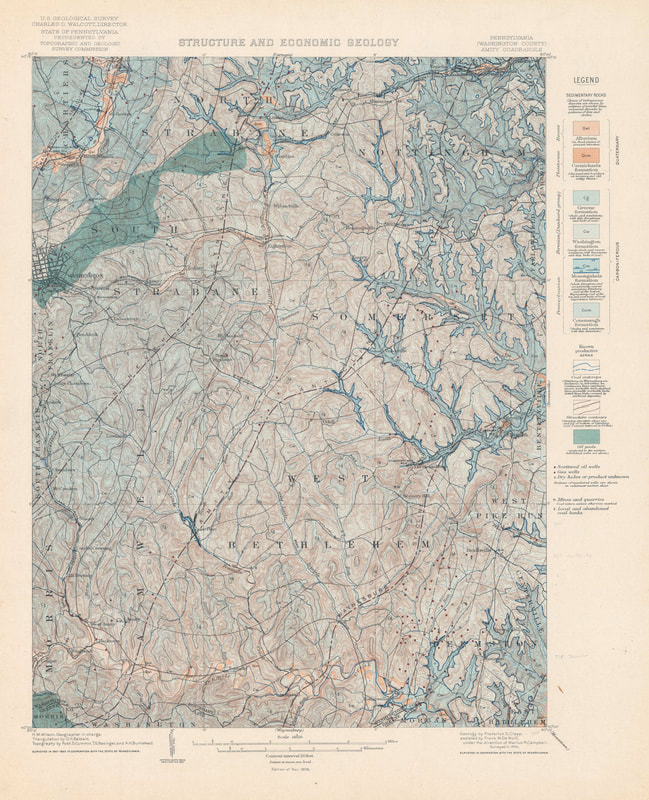

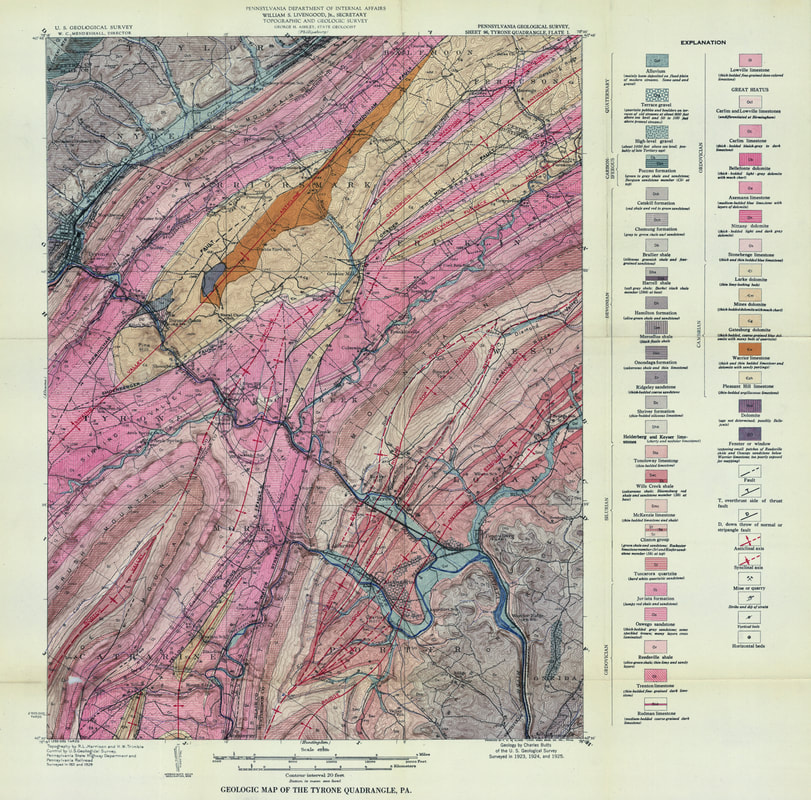

This standardized approach to mapping was implemented under the auspices of the next USGS Director, Charles Doolittle Walcott. The results can be seen in the USGS “Folios of the Geologic Atlas of the United States”, a series published between 1894 and 1945, which included maps of topography and geology with an emphasis on structure and economic geology (see Figure 5 for an example from the Little Belt Mountains in Montana; Weed, 1899). Some of these folios also included structural contours on the maps (see Figure 6 from Clapp, 1907).

“Fault lines (particularly when they are formation boundaries) shall be indicated when actually traced by somewhat heavy full lines in black; and when not actually traced, by similar broken lines, toward which the formation devices may blend or fade as circumstances seem to require.”

(Powell, 1890)

This standardized approach to mapping was implemented under the auspices of the next USGS Director, Charles Doolittle Walcott. The results can be seen in the USGS “Folios of the Geologic Atlas of the United States”, a series published between 1894 and 1945, which included maps of topography and geology with an emphasis on structure and economic geology (see Figure 5 for an example from the Little Belt Mountains in Montana; Weed, 1899). Some of these folios also included structural contours on the maps (see Figure 6 from Clapp, 1907).

Figure 5. An example map from the Folios of the Geological Atlas of the United States. In this example from 1899, faults are represented by solid and dashed black lines following the guidelines laid down by Powell in the 1880s. The inclusion of sections on the map is unusual but emphasizes an increasing focus on geological maps for resource exploration. Note that the map title now includes the term “Structure”.

Figure 6. In this map from the “Folios of the Geological Atlas of the United States” series, the geologists have included structural contours in addition to stratigraphy, lithology, and structure (Clapp, 1907)

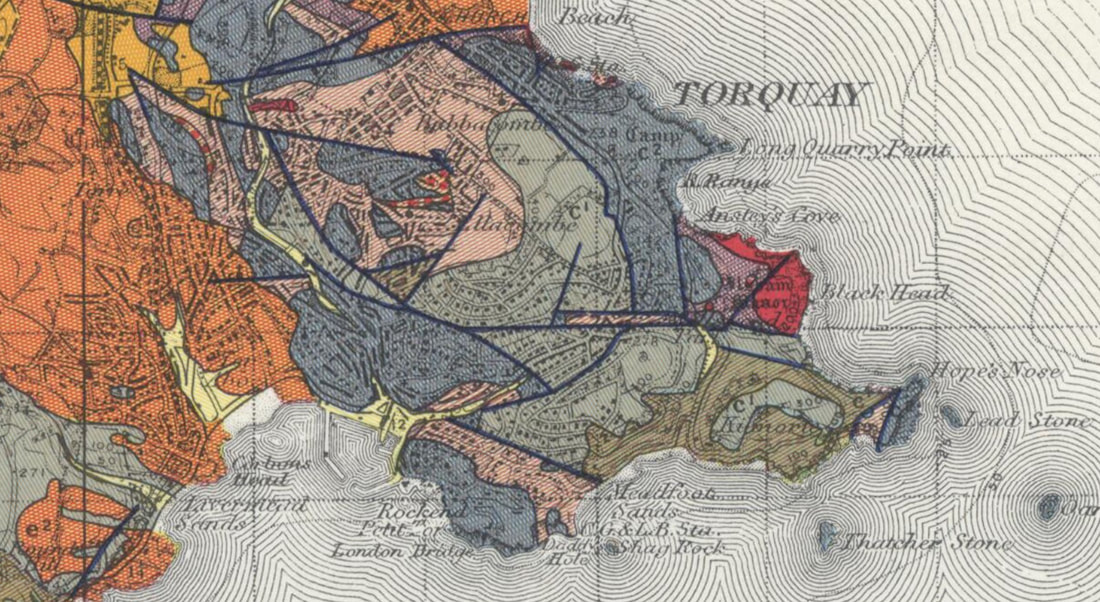

The folios of Walcott during at the turn of the 19th-20th centuries look remarkable modern. But this ‘standard’ symbology does not seem to have been systematically adopted more widely outside of the U.S.. The British Geological Survey continued to mostly use white lines to represent faults until around 1912, after which they were changed to darker colors such as dark browns (Fowler et al., 1926) or dark blue lines (Ussher and De la Beche, 1953) (Figure 7). Although Strahan’s geological map of Ingleborough in 1910 (Strahan, 1910) users black lines and is more similar to Powell's scheme and the USGS folios.

Figure 7. White solid lines continued to be used by the British Geological Survey until at least 1912 (left)(Ussher and De la Beche, 1912). Subsequent editions such as this reprint from 1953 (Ussher and De la Beche, 1953) show faults in dark blue (right image). This was not universal with Strahan’s map of Ingleborough in 1910 representing faults with black solid lines (Strahan, 1910). British Geological Survey materials © UKRI (1912) British Geological Survey (BGS) | large image viewer | IIPMooViewer 2.0 and (1953) British Geological Survey (BGS) | large image viewer | IIPMooViewer 2.0 (this is actually the 1962 reprint of the 1953 map)

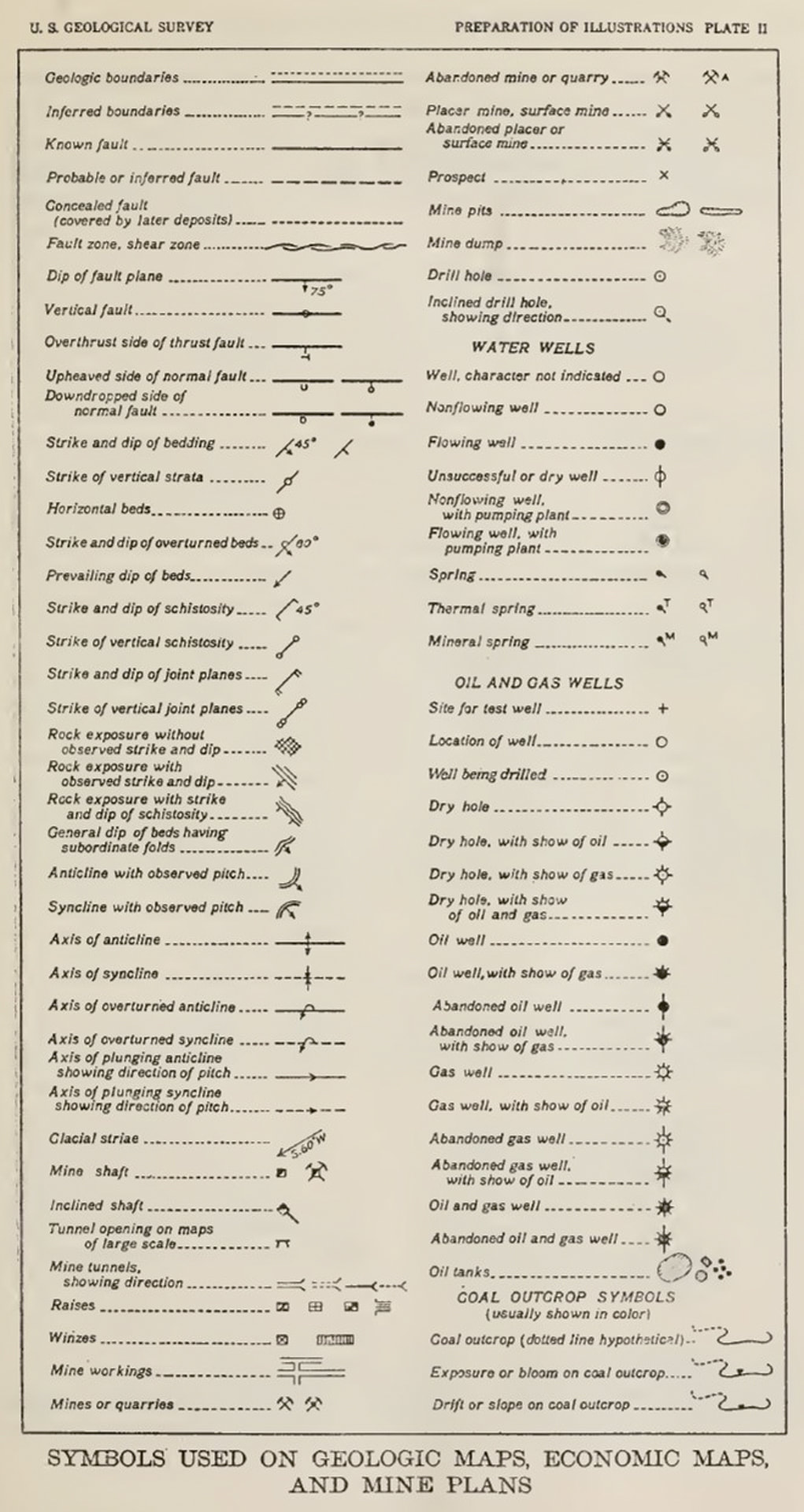

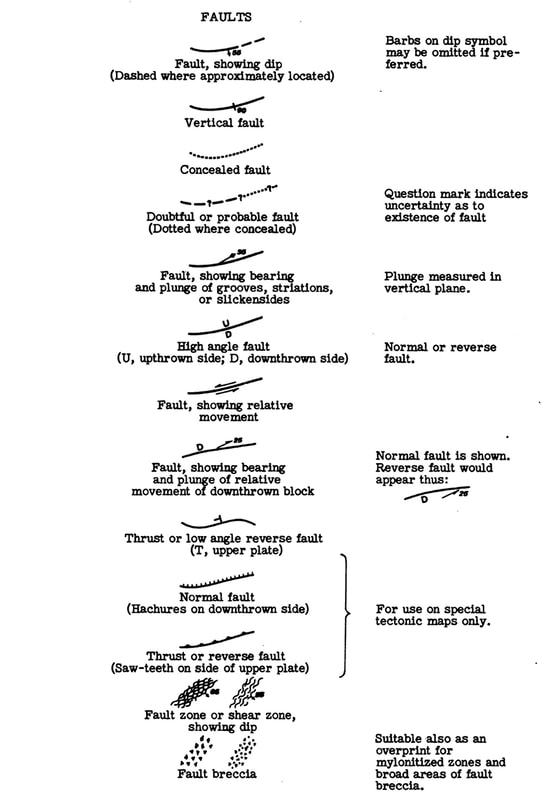

The nomenclature of Powell was expanded in 1920, when the USGS published formal guidance to its geologists on how to prepare illustrations and maps (Ridgway, 1920). Faults on maps were now represented by lines with associated marker symbols to indicate the footwall and hanging wall sides of normal faults, and overthrust (upper plate) side of thrusts. Anticlines and synclines were represented by a line along the fold axis, differentiated by arrows perpendicular to the line - a symbology that has changed little since (Figure 8).

Figure 8. The map symbol set presented by the USGS in 1920 (Ridgway, 1920)

This map nomenclature was quickly adopted and most clearly exemplified in the detailed local USGS maps of the time, for example, the excellent 1929 geological map of the Tyrone quadrangle in Pennsylvania (Figure 9) in which thrust faults, normal faults, synclines, and anticlines were differentiated (Butts, 1929). In Britain, the 1:63,360 map of Norham used a tick mark to denote the downthrown side of faults (Fowler et al., 1926). But we can also see its use in exploration maps during the following decades (Figure 10). And it was the oil Industry that then started to drive the need for more significant differentiation in the structural elements symbol set.

Figure 9. The 1929 geological map of the Tyrone quadrangle in Pennsylvania (Butts, 1929). Note the use of different symbols for anticlines, synclines, normal and thrust faults. Many of the fold axes are named. Image made available online courtesy of the Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 10. The Los Angeles City Oil field showing fold axes and faults in the 1940s (Jenkins, 1943)

The need for more symbols

It was becoming clear that there was a much greater diversity of structural models – different fold and fault types - that needed to be represented graphically (Boyer and Muehlberger, 1960; Crowell, 1959; Davis, 1913; Hill, 1947; Hubbert, 1927; Reid et al., 1913; Sopwith, 1875; Straley III, 1934).

In 1950 the USGS expanded the range of recommended fold and fault symbols (Cloos et al., 1950), including many that we still use today. But it still lacked the diversity of symbols that we use today. It also restricted some symbols to specific types of maps (Figure 11).

In 1950 the USGS expanded the range of recommended fold and fault symbols (Cloos et al., 1950), including many that we still use today. But it still lacked the diversity of symbols that we use today. It also restricted some symbols to specific types of maps (Figure 11).

Figure 11. The additional fault symbols suggested by Cloos et al. (1950) for the USGS. It is interesting to note that although the saw-tooth marker symbol for thrust and reverse faults is illustrated, it is only "for use on special tectonic maps".

From 1989 to 1995, the USGS built a more extensive cartographic standard map symbol (Reynolds, Queen and Taylor, 1995; Soller, 1996). In this version, all thrust faults were represented using the saw-tooth marker pattern, which is now the most widely used visualization. Normal faults were still represented by a tick mark to indicate the downthrown side. This was further expanded with the 2006 update to the USGS symbol set (Federal Geographic Data Committee, 2006). However, confusingly here, the USGS chose to represent normal faults with half-circles indicating the downthrown side and rectangles to represent the upthrown block of reverse faults. Unfortunately, by this time, other structural geologists and many companies had already appropriated the idea of using rectangle markers but to replace the tick marks on normal faults (Hulshof, 2012; Markwick, 2019); this included Robertson Research in the late 1990s, which is where I got into the habit. Other organizations, such as the BGS, continue to use tick marks (Mawer, 2002).

With this diversity of map symbols, we can create a more detailed map of the ‘structural framework’ built of structural elements. These are the map representations of the structure rather than the whole structural form: a fold axis, not the entire fold form, a fault trace at the surface (or top sub-surface fault trace), not the whole fault plane. It is these elements that are recorded in our Structural Elements database.

This distinction may seem like semantics. But it is important, and as we stressed at the beginning of this article, it is a function of the application. In New Ventures exploration or plate modeling or paleogeography, we need to understand the overall structural context and what it tells us about geodynamic evolution, whether for basins or basin hinterland. But at the prospect scale, we need to understand the form.

This explains why we distinguish between the “structural framework” and the “crustal architecture” of which the framework is an integral part in our paleogeographic workflow.

A further complication here is that when we talk about ‘crustal’ architecture, we are, of course, referring to the whole lithosphere - nothing is ever simple!

With this diversity of map symbols, we can create a more detailed map of the ‘structural framework’ built of structural elements. These are the map representations of the structure rather than the whole structural form: a fold axis, not the entire fold form, a fault trace at the surface (or top sub-surface fault trace), not the whole fault plane. It is these elements that are recorded in our Structural Elements database.

This distinction may seem like semantics. But it is important, and as we stressed at the beginning of this article, it is a function of the application. In New Ventures exploration or plate modeling or paleogeography, we need to understand the overall structural context and what it tells us about geodynamic evolution, whether for basins or basin hinterland. But at the prospect scale, we need to understand the form.

This explains why we distinguish between the “structural framework” and the “crustal architecture” of which the framework is an integral part in our paleogeographic workflow.

A further complication here is that when we talk about ‘crustal’ architecture, we are, of course, referring to the whole lithosphere - nothing is ever simple!

We all know what a structural map is. Don't we?

So, what was the cause of the problems that John and I had?

In truth, even with 15 years of hindsight, I still do not fully understand the causes. But I think I have more of an idea than I did then.

What is a structural map? When looking at the example in figure 1, everything seems obvious. John and I had assumed that all structural geologists saw a structural map, in the same way, especially the most experienced structural geologists, those with the most years. But what they ‘knew’ and we ‘knew’ turned out not to be the same.

In our defense, I should point out that we ultimately hired a brilliant Polish structural geologist, whose tectonic model of SE Asia is, I still think, one of the best solutions I have seen for that area. And then a series of excellent MSc graduates who all immediately understood what we meant. So perhaps it was also partly the individuals concerned after all? Perhaps…

Structural mapping is fundamental to solving geological problems, especially in resource exploration. Getting the structural framework right impacts everything else, which we then build upon it.

As geologists, we all ‘know’ what a structural map is. But what we ‘know’ has changed through time, depends on the application, and, as it turns out, it may also depend on the geologist you ask.

So what have I learned? Always explicitly define what you mean and assume nothing.

In truth, even with 15 years of hindsight, I still do not fully understand the causes. But I think I have more of an idea than I did then.

What is a structural map? When looking at the example in figure 1, everything seems obvious. John and I had assumed that all structural geologists saw a structural map, in the same way, especially the most experienced structural geologists, those with the most years. But what they ‘knew’ and we ‘knew’ turned out not to be the same.

In our defense, I should point out that we ultimately hired a brilliant Polish structural geologist, whose tectonic model of SE Asia is, I still think, one of the best solutions I have seen for that area. And then a series of excellent MSc graduates who all immediately understood what we meant. So perhaps it was also partly the individuals concerned after all? Perhaps…

Structural mapping is fundamental to solving geological problems, especially in resource exploration. Getting the structural framework right impacts everything else, which we then build upon it.

As geologists, we all ‘know’ what a structural map is. But what we ‘know’ has changed through time, depends on the application, and, as it turns out, it may also depend on the geologist you ask.

So what have I learned? Always explicitly define what you mean and assume nothing.

Further Information

If you would like to learn more about the Knowing Earth suite of structural and crustal architecture databases or any of our other Knowing Earth databases, please contact me at paul.markwick@knowing.earth.

This blog is part of a longer paper on the history of structural mapping that will be presented later this year.

The first version of the cartographic symbol set used by Knowing Earth was published as part of Markwick (2019) and is available through the Geological Magazine website https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/geological-magazine/article/abs/palaeogeography-in-exploration/444CC2544340A699A01539A2D4C6E92A

The associated ArcGIS style file can be downloaded from my research website: www.palaeogeography.net

We will be publishing our new 2021 version shortly.

Others symbol sets available on-line.

USGS: https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/fgdc_gds/geolsymstd/download.php

BGS: http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/3221/1/RR01001.pdf

Shell: https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=8a89e7ffe4154efa94c65090c4dab485

Knowing Earth: http://www.palaeogeography.net/publications.html

This blog is part of a longer paper on the history of structural mapping that will be presented later this year.

The first version of the cartographic symbol set used by Knowing Earth was published as part of Markwick (2019) and is available through the Geological Magazine website https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/geological-magazine/article/abs/palaeogeography-in-exploration/444CC2544340A699A01539A2D4C6E92A

The associated ArcGIS style file can be downloaded from my research website: www.palaeogeography.net

We will be publishing our new 2021 version shortly.

Others symbol sets available on-line.

USGS: https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/fgdc_gds/geolsymstd/download.php

BGS: http://nora.nerc.ac.uk/id/eprint/3221/1/RR01001.pdf

Shell: https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=8a89e7ffe4154efa94c65090c4dab485

Knowing Earth: http://www.palaeogeography.net/publications.html

References cited

Boyer, R. E. & Muehlberger, W. R. 1960. Seperation versus slip. AAPG Bulletin 44, 1938-39.

Butts, C. 1929. Geologic map of the Tyrone quadrangle, Pa. Harrisburg, Pa.: Pennsylvania Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey.

Clapp, F. G. 1907. 144. Amity folio, Pennsylvania. In Folios of the Geologic Atlas: USGS.

Cloos, E., Pusey, L. B., Rubey, W. W. & Goddard, E. N. 1950. New list of map symbols: [for use in publications of the Geological Survey]. p. 6. Washington, D.C.: United States Geological Survey.

Crowell, J. C. 1959. Problems of fault nomenclature. Bulletin of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists 43 (11), 2653-74.

Davis, W. M. 1913. Nomenclature of surface forms on faulted structures. GSA Bulletin 24 (1), 187-216.

De la Beche, H. T. 1830. Sections & views, illustrative of geological phaenomena. London: Treuttel & Würtz, 71 pp.

De la Beche, H. T. 1845. 1:63,360 geological map series [Old Series] Sheet 19, [Bath, Frome, Axbridge, Wells, Glastonbury, Bruton, Mere, Somerset Coalfield, and southern part of Bristol Coalfield.] , Solid. Geological Survey of England and Wales.

Federal Geographic Data Committee 2006. FGDC digital cartographic standard for geologic map symbolization. p. 290. Reston, VA.: Prepared for the Federal Geographic Data Committee by the U.S. Geological Survey.